During the writing process of his New York Times best-selling book The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg (ironically) developed a habit of his own (and a bad one at that): going to the canteen every day and buying a chocolate chip cookie.

Duhigg humorously recounts, in his book of the same name, how this bad habit began causing him problems at home:

“Let’s say this habit has caused you to gain exactly eight pounds, and that your wife has made a few pointed comments”.

Duhigg relied on reminding himself not to eat (by posting a post-it note to his computer that read: “No more cookies”), but it was no use. [1]

Does this sound familiar? If so, you’re not alone. This common scenario goes like this: You decide you want to break a bad habit (such as binge eating) and you remind yourself not to do it (by removing unhealthy foods from your house), but no matter how hard you try, you can’t break your bad habit. You drive to the nearest convenience store, buy unhealthy snacks and return to your old ways.

I made this mistake for years. I would try and will myself not to do an unwanted behaviour, only to experience decision fatigue and return to it (and often with greater intensity). That is until I learnt how a habit works and in particular: “The Habit Cycle”.

The Habit Cycle

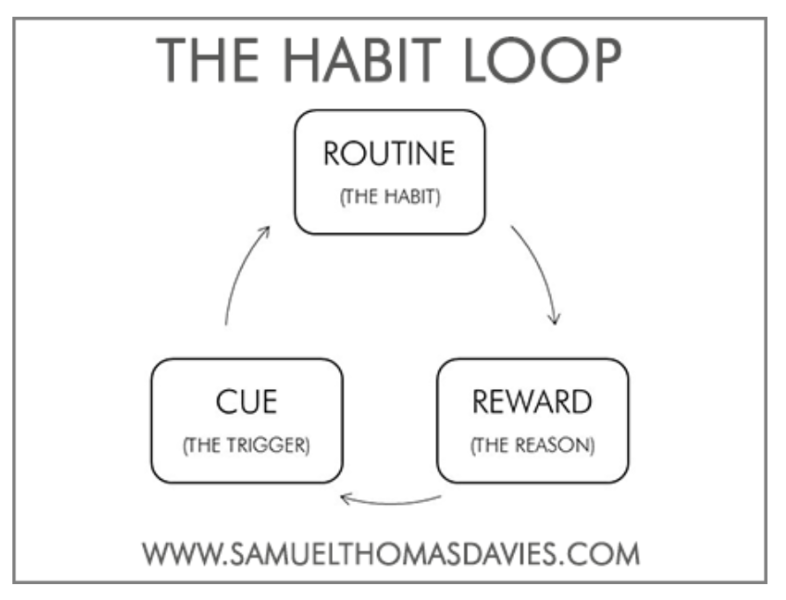

In the 1990s, researchers at MIT discovered a neurological loop at the core of every habit. This loop that consists of three parts: a cue, a routine and a reward. See Figure 1.

The cue is the trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. The routine is the behaviour itself. This can be an emotional, mental or physical behaviour. The reward is (1) The reason you’re motivated to do the behaviour and (2) A way your brain can encode the behaviour in your neurology if it’s a repeated behaviour.

For example, if your bad habit is online gambling, your cue may be boredom, your go-to routine may be to go online and gamble and your reward may be the thrill of winning money (not to mention the chemical reward with the release of dopamine).

Once the brain begins to crave the reward, the habit becomes automatic.

The problem is, because all habits follow this loop, your brain can’t differentiate between a good habit and a bad habit. This is why it’s difficult to break bad habits.

However, with the correct framework, you can begin to re-engineer how your habit works.

Let’s look at the four step process you can use to break a bad habit.

The Framework

The framework for re-engineering a habit is as follows:

Identify the routine

Experiment with rewards

Isolate the cue

Have a plan

In order to maximise your chances of breaking your bad habit, I would invite you to imagine you’re a scientist and this is an experiment you’re conducting. With that said, let’s look at each step in more detail.

Step 1: Identify The Routine

The routine is obvious: it’s the behaviour you want to change. What is the bad habit you want to break? This may be abusing drugs, binge eating, biting your fingernails (guilty), complaining, drinking alcohol, (online) gambling, lying, smoking or thinking negatively to name a few. If, for example, your bad habit was over-eating, you would put that in the routine part of the habit loop.

Next, you need to identify what your cue and your reward is for your habit.

Step 2: Experiment With Rewards

Rewards are powerful because they satisfy your cravings. The problem is you’re often unaware of the craving that’s motivating your behaviour to begin with. You may argue: “But what’s rewarding about a bad habit like biting my fingernails? I hate it!” Even habits we dislike and want to break will have a reward that will cause you to do it. It’s probably a reward you haven’t even considered, as Duhigg comments:

“[Rewards are] obvious in retrospect, but incredibly hard to see when we are under their sway”.

On the first day of your experiment, when you feel the urge to do your bad habit, change your routine so it delivers a different reward. For example, if your bad habit is eating sugar, try eating an apple instead.

The next day, repeat the process.

The point is to test different hypotheses to determine which craving is driving your routine.

Your goal is to look for recurring patterns. To do this, after each activity, write down on a piece of paper or on your phone, the first three things that come to mind. These can be emotions, random thoughts, reflections on how you’re feeling, or just the first three words that come to mind.

Then set an alarm on your phone for fifteen minutes. This is to identify the reward you’re craving. When it goes off, ask yourself: “Do I still feel the urge to do my bad habit?”

To return to the previous example, if you’re still craving sugar after eating an apple, then your craving isn’t motivated by hunger (otherwise, your craving would’ve been satisfied) – it’s motivated by a different reward.

If, however, you called a friend and at the end of your fifteen minutes you no longer craved sugar, then calling your friend – a temporary distraction from you mundane routine – is your reward.

The reason why it’s important to write down three things is (1) It forces you to become aware of what you’re thinking and feeling and (2) At the end of the experiment, when you review your notes, it’ll be much easier to remember what you were thinking and feeling the moment your fifteen minutes were up.

By experimenting with different rewards, you can isolate the reward you’re actually craving rather than what you think you’re craving. This is essential in re-engineering your habit.

Step 3: Isolate The Cue

Psychologists at Western Ontario University discovered almost all habitual cues fit into one of five categories:

- Location

- Time

- Emotional state

- Other people

- Immediately preceding action

This is why habits like smoking are difficult to quit: There are multiple cues.

When you feel the urge to do your bad habit, ask yourself:

Where am I?

What time is it?

What’s my emotional state?

Who else is around?

What action immediately preceded my urge?

Do this for a minimum of five days and look for recurring patterns. For example, if you notice by the fifth day you’ve written down “boredom” for emotional state five times, then boredom is likely your cue.

Step 4: Have A Plan

Now you’ve identified your cue and your reward, you need to use what psychologists call an “implementation intention” or what I like to call an “if/then strategy”.

This can be written as: “If I feel the urge to (X) then I’ll do (Y)”. For example: “If I feel the urge to (eat sugar) then I’ll (call my friend)”.

This takes a lot of practice; you may forget to do your new routine and fall back into your old habit, but with commitment (and a reminder to do your new routine instead of your old one) it will work. If you apply The Daffodil Principle and commit to one daily action until you break your bad habit, it will help facilitate the process.

Epilogue

Duhigg followed this framework to try and break his chocolate chip cookie habit. Here are the results from his experiment:

“I don’t have a watch anymore – I lost it at some point. But at 3:30 every day, I absentmindedly stand up, look around the newsroom for someone to talk to, spend ten minutes gossiping about the news, and then go back to my desk. It occurs almost without me thinking about it. It has become a habit”.

Your habits aren’t destiny and using this new science of habit change, you can regain control and change them – once and for all. ![]()

Sources

[1] Duhigg, C. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do and How to Change. New York: Random House, 2012. Print.

[2] Graphic based on Charles Duhigg’s “The Habit Loop” in The Power of Habit.