Stay Away From The Beaches Because There Is Something In The Water

The creature had looked like an extended, floppy hand. Like the ones from the fifty cent machine I used to throw against the wall and watch crawl down the paint.

My sister pranced past in her swimsuit, two triangles at the top with a poodle skirt styled bottom. Red and white polka dots covered both.

“Come on,” she said, tugging my sunscreen slick arm. “Mom doesn’t want me going in alone.”

“Guess you’re not going in then,” I said. I patted down my heap of sand with a cupped hand, smoothing the edges to create a dome. The base of the castle.

Tiff could play the disappointed little sister act, but she knew I would refuse to join her in the water. I never splashed ocean salt in her face or created a whirlpool of chlorine back at our house. I never dipped a finger inside, let alone dunked my head under.

Instead, I made sandcastles. Mud pies. Houses constructed of dirt and shells and sticks. I created when the water only destroyed. Sagged the walls of my buildings, wiped my castles clean away.

“And everyone calls me the baby of the family,” she said, forming the famous pout our parents and her grade three teacher gave into every time.

No sense in fighting back, in listing out excuses. I could lie to my friends about how I had never learned how to swim. I could hint to my mom about how uncomfortable I felt removing my shirt and revealing my pimpled preteen body. But Tiff knew the truth, because she stood hand-in-hand with me the day it happened.

We had been rolling matchbox cars around the kitchen, propping spoons and spatulas and even knives against table legs to use as ramps. Tiff had lost every race, only being three at the time, so I kept thinking of new handicaps to make it more fun. I’d tried snapping my eyes closed, using my toes to control the car instead of my fingers, and finally filling up my favorite pickup truck with water to see if it could win a race without spilling any.

After soaking the toy, I’d twisted the tap off, but not all the way, so the faucet drip-drip-dripped as plastic tires scraped against the tiles.

I’d ignored the sound, barely even registered it, and won that race. And the next one. And the…

The dripping had turned to a stream, which turned to a surge of water, the sound as loud as a subway train bursting through its tunnel. I’d reached for Tiff on instinct, grabbing her tiny hand to protect her – from who? from what? – and the water stopped, like something had blocked it. Like something lodged itself in the crack.

Still attached to my sister, I’d lifted onto my tiptoes and stared into the sink. Something poked out from the faucet an inch, clear and sparkly.

It had looked like solid water. Not frozen, not ice. Solid, like it had taken shape and stayed that way.

I’d tried not to hurt Tiff with my grip, concentrating my fear on my other hand, the one balled into a tight fist. I’d wanted to tell her it would be okay, but knew my voice would shake and shiver if I tried.

I’d just stood there instead, watching the thing slide out another inch and two and three. A thick cylinder with an end that moved like a snake head, left and right, up and down, seeking and searching. Then, with a pop that sounded like a water balloon, a thumb jutted out from the head, making it look more like a mitten.

Four more pops, each causing a jump from me and a whimper from Tiff.

Now, the creature had looked like an extended, floppy hand. Like the ones from the fifty cent machine I used to throw against the wall and watch crawl down the paint.

The hand had hung in the air for a moment before flopping over the edge of the sink. It had slithered down to the tiles until its fingers hit the floor and skittered forward. Somehow, it stayed connected with the faucet that birthed it, a never ending arm that grew and grew.

Braver then than now, I had grabbed a knife from the makeshift race track and jabbed at the hand. Pierced the blade through the center of the palm.

It had stiffened and collapsed into a puddle.

Tiff had stiffened and collapsed onto me.

When my parents had come home, they took turns screaming questions about why-is-the-floor-soaked and why-is-your-sister-crying and were-you-playing-with-knives and why-is-your-crotch-wet?

But that interrogation felt painless compared to the weeks after. Kids at school made fun of my stink because I refused to bathe. Dad looked at me funny when I cleaned my hands with sanitizer instead of sink water. And mom had a field day when she found the Gatorade bottle I peed into to avoid the splash of the toilet.

To cure what they wrongly diagnosed as OCD, my parents sent me to a lifetime’s worth of psychiatrist visits. After explaining what I had seen countless times and being accused of hallucinating each one, I weaned myself back to being normal.

Now, I showered (for five minutes tops), peed (in the bushes whenever I could get away with it), drank (milk and energy drinks, mostly), and washed my hands (when sanitizer wasn’t available). I fought hard to appear normal.

But I refused to submerge myself in the water. A little pool around my feet during a shower, I could handle. But willingly jumping into a deep, expansive sea? No way in hell.

“Water monsters aren’t real,” Tiff said, squeezing a towel around her hair, snapping me from past to present. She must have already lapped through the water. I must have zoned out while she wandered off. I must have been lost in a memory when I should have been watching my sister.

She could have drowned. She could have gotten swept up in a current and yanked into the darkness. She could have died because of me.

That mistake must have bothered her as much as me, but she acted unconcerned until that night. Until she strode into our shared bedroom, the one dad kept swearing he would split once he got the carrot-on-a-stick promotion he had been promised for the last decade.

When Tiff sunk onto her bed, she cocked her head at me, smirk in place.

“What?” I asked, eyebrows popped. Did she find another one of my journals? A pair of dirty underwear? A stash of cash?

Smarter than anyone her age should ever be, she always found new ways to blackmail me with ease. Some family members placed bets about whether she would grow up to be a criminal or a lawyer. I stuck to the later, choosing to believe in her, choosing to stick with my best friend in…

Then I heard it.

The drip-drip-drip.

“What the hell, Tiff?” I asked, my palms pressing against bed sheets and springing me to my feet.

“You have mom, dad, and the psych… the psychia – ” She stumbled over the word. “ – the doctors all fooled, but I know you’re not better. You got to get over this.”

“Plenty of people are afraid of the deep sea.”

“It’s more than that.”

“I can shower. I can take a shit. I’m fine, Tiffany.”

She folded her arms. “The shower never grew a hand. Neither did the toilet. The sink did.” The razorblade edge to her voice dulled when she said, “Leave it on. Just for tonight. Please?”

“You’re the one always begging us to recycle soda cans and cut apart those plastic rings to save the seagulls,” I said. “You really want to waste water?”

She stared me down. Hard. “Yes. I really do.”

I wondered how well she retained the memory from five years ago – or if she only remembered the stories I repeated to her. About how I had left the water on. About how it had given the creature time to solidify. To slither out from the pipes in our ancient home.

Somehow, a girl half my age and three-quarters my size had pinpointed my biggest fear. I could shower for five minutes, sit on the toilet for five minutes, and wash my hands for five seconds, but I could never do those things for an extended period of time. She must have noticed the way I rushed through my bathroom time. The way I called for her if she took too long behind the locked door.

While I was thinking of how I hated my parents for being out that night on a search for something to sniff instead of taking care of their own children, and how I hated my sister for putting me through my own personal hell, she pulled something from her jeans and rested it on my nightstand.

A butcher knife.

“Just in case,” she shrugged, as if she considered a water monster attacking us a real possibility, which I knew she didn’t. I knew she no longer trusted her own memory, that she thought I belonged in the psychiatric unit. But I understood what she meant: I hope this makes you feel a little better. I just want you to get better.

I responded with silence, popped my earbuds in to drown out the dripping, and forced myself to sleep. And somehow, it actually worked. My head sunk into the pillow and I drifted off to sticky dreams, the kind I would remember in the morning. Of my parents kissing over coffee and my sister hanging her law degree. Of us chatting about things normal families dealt with, like marriage and school loans and taxes. Against all odds, I felt at peace.

Until something sloshed over my leg. A coldness.

I woke up with closed eyes, hesitating to open them, afraid of what I would see. Afraid of the disembodied hand I imagined floating over me.

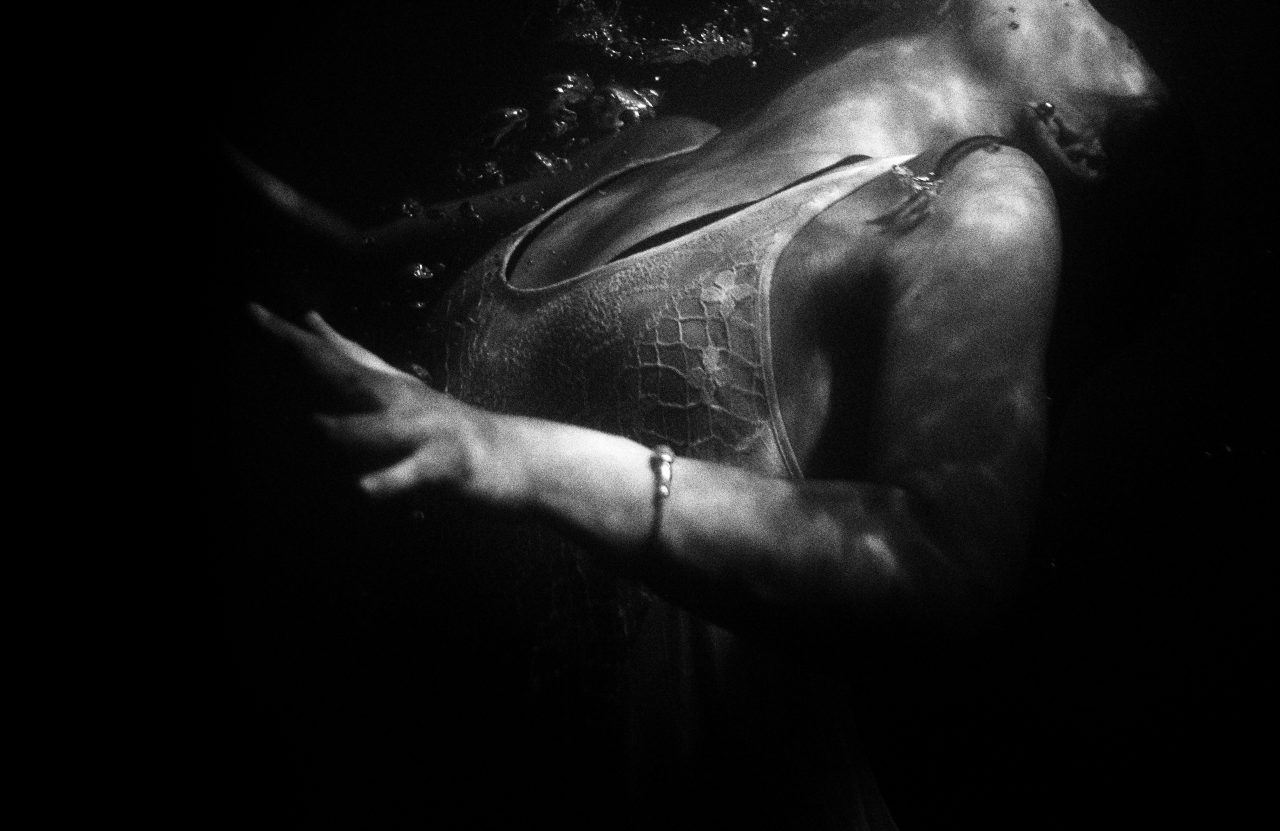

When I finally found the strength to click my lids open, I discovered more than a hand. Because more than a few minutes had gone by, because hours had passed, the creature had enough time to form a full body. Two arms and two legs and a longer torso than any human man could ever possess.

It reminded me of clear gelatin, see-through but solid. A nose protruded from its skull and two deep indentations made up the eye sockets.

The creature clamped a hand over my mouth, but instead of suffocating me, instead of stealing air from my lungs, water flowed into me. It spilt from my mouth, splashed down my throat, weighed down my stomach.

I slung my arm across my nightstand, slapping my hand against the wood as I groped for the knife. I grabbed a notebook instead. Then a pen. A ruler. A sock. When I finally felt my fingertips graze the weapon, I struggled to scoot it close enough to grip.

What would happen if the creature killed me? Would the police accuse Tiff of drowning me? Would they send someone so young to juvie? No. They would consider it a suicide. My parents would hate me for making them look bad, for making them waste thousands on a funeral. Tiff would be heartbroken, consider it her fault. The psychiatrists would lock her up in an institution if she uttered a word about the water.

I fought to sit up, to let the water fall out of my nose and mouth, but the creature straddled me. Its face over my face and chest over my chest. Pinning me into place. Sentencing me to an excruciatingly slow trip toward the reaper.

Beneath the coldness of the monster’s body, I felt a warmth against my wrist. Fingers. Human fingers.

Tiff.

Our eyes connected through the clear body and she squeezed, once, twice, giving me the same wordless comfort I gave her during mom and dad’s arguments. Reminding me it would be okay soon.

In five slow motion seconds, she grabbed the knife, climbed onto the edge of the bed to give herself height, and pierced the creature with the blade.

She must have swung her arm hard, too hard, because it slipped straight through the water, stabbing into the beast, stabbing through the beast, and into the flesh below.

The pop came next, delayed. It exploded the creature into thick droplets, an eruption of rain, soaking my fresh corpse. ![]()