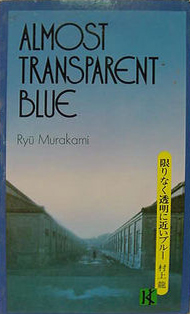

Almost Transparent Blue by Ryu Murakami

Almost Transparent Blue (1976) was written by Ry? Murakami (b. 1952) while he was a student at Musashino Art University, where he was enrolled in the sculpture program. It was his first novel and was awarded the Akutagawa Prize (Japan’s “most sought after” literary prize; previous winners include Kobo Abe and Kenzaburo Oe) and sold…

By Tao Lin

Almost Transparent Blue (1976) was written by Ryu Murakami (b. 1952) while he was a student in the sculpture program at Musashino Art University. It was his first novel and was awarded the Akutagawa Prize (Japan’s “most sought after” literary prize; previous winners include Kobo Abe, Kenzaburo Oe) and sold ~1.2 million copies (~1% of Japan’s population at-the-time) in six months. In comparison Less Than Zero (1985) sold ~50k copies (~.021% of America’s population at-the-time) in twelve months.

It is 127 pages in English, set over seven days in early 1970s Japan near an American air force base, near Tokyo, and is written in past-tense first-person. The narrator, Ryu, is 19 and has a vague relationship with Lilly, a maybe former-fashion-model and maybe current-prostitute who works in a bar/restaurant. Most scenes are of Ryu and Lilly talking and using drugs or Ryu and his other friends, separate from Lilly, talking and using drugs, mostly in his apartment. One scene is an orgy and one scene is an outdoor concert. About halfway into the book Ryu and Lilly ingest mescaline and drive without a plan in a thunderstorm. The book ends with a one-page letter from Ryu to Lilly that begins “Lilly, where are you now? I think it was four years ago, I tried going to your house once more, but you weren’t there. If you read this book, get in touch with me.”

SINGLE-SENTENCE EXCERPTS

The red ceiling light was reflected on the surface of the brownish vomit on the newspaper.

Moko said, “Ryu, put on some music, I’m sick of just fucking, I think there must be something else, I mean, some other ways to have fun.”

I could see into the kitchen from where I sat.

The Nikomat lens reflected a dark sky and a small sun.

Hey, just like butterflies, said Reiko, taking a piece of the cloth and spreading butter on Durham’s prick.

Bob’s huge cock was stuffed all the way into Kei’s mouth.

After rubbing her body with a piece of bacon, Jackson sprinkled on vanilla extract.

Even when I gently peeled the band-aid off her ass, Moko didn’t open her eyes.

Then he turned to me—my finger still in Moko’s ass—and said, Last night when you guys were messing around I got a straight flush, you know, really right on, a straight flush in hearts—Hey, Kazuo, you were there, you can back me up, right?

From where I stood I could hear words like “pigsty” and “marijuana.”

The inside of the train glittered.

Reiko stood up, her face greenish pale, muttered, What time is it now, what time is itu To no one in particular, staggered to the counter, took the whiskey from Kei’s hand, poured some down her throat, and had another violent fit of coughing.

Without answering she crunched and swallowed five Nibrole pills.

HOW I LEARNED ABOUT IT

I think I learned of Ryu Murakami (b. 1952) when looking at books by Haruki Murakami (b. 1949) in 2002 or 2003. The back cover of Ryu Murakami’s books said “renaissance man” and that he’s been a movie director (of his own books), a talk-show host, played in rock bands. The next six to eight years I read maybe ten Haruki Murakami books, one Haruki Murakami biography, zero Ryu Murakami books. Sometimes I thought things like “what do people think about them having the same last name, similar publishing credits, similar age” and didn’t think anything except maybe “seems…something” or “seems…interesting.”

At some point, in 2009, I think, I read Snakes and Earrings (2003) by Hitomi Kanehara (b. 1983) and liked it and learned that Ryu Murakami was on the prize committee that awarded it—and The Back You Want To Kick (2003) by Risa Wataya (b. 1984) which is not available in English—the Akutagawa Prize in 2003 (notably, as previously the youngest winners were all males over 23) and was quoted as saying “easily the top choice, receiving the highest marks of any work since I became a member of the selection panel.” Around this time I also read somewhere that Almost Transparent Blue was about self-destructive, apathetic, “lost” youth—which is how a certain kind of book I like reading is usually inaccurately, I feel, described.

FIRST READING

I had very little sense of time, due to a lack of connectors like “two days later” or “one week later,” and vaguely intuited that the events occurred over weeks or months and maybe nonlinearly. I felt that the book might be a series of self-contained scenes and that the author maybe didn’t consider chronology or plot, but simply related what he viewed as interesting scenes. I didn’t feel that having a sense of time, on the day/week/month level, would affect my experience of the book, and was mostly focused on tone, I think.

I felt somewhat surprised by the orgy. I felt overall that the book was funny, interesting, readable, and had successfully avoided “stock phrases.” Near the end, in [19], things seemed to become more abstract, and I read the last ~20 pages less attentively, viewing it as a tonal aberration, caused by the author maybe feeling pressure to “do something.”

SECOND READING

I reread it a few months later—April or May, 2010—for this essay, sort of idly, from something like 4AM to 7AM, lying on my bed, sometimes typing notes onto my MacBook. I noticed that some scenes contained details that referenced other scenes, in a manner that I quickly began to “sense” that the book was tightly-structured and plotted—that Ryu Murakami had a clear sense of the book’s movement and each of the characters’ personalities and histories—but in a manner that would not be discernible to me unless I outlined it, in part due to the large number of characters. I felt excited to read the book with increased attention, knowing I probably wouldn’t find any sentences that were contextually incoherent, physically contradictory/impossible, or tonally inconsistent.

Instead of “dismissing” certain sentences whose intentions I didn’t immediately comprehend I began to focus on those sentences more, viewing them as interesting rather than vaguely or carelessly written, in the same manner that if I’m remembering one week of my life where I did a lot of things with a lot of different people I would view details that were more difficult to assimilate into my memory as the more interesting—and ultimately more memorable—details, I think.

I noticed that the narrator focused on describing (to the reader) exterior things, like cockroaches or light filaments, while engaged in dialogue—even when he was the one speaking—in a manner that made me feel calmly emotional, maybe simply because the narrator, in his ability and motivation to describe things that seemed irrelevant to his thoughts and the thoughts of the people around him, with interest and detachment, seemed calm. I felt less that the book was funny and more that it was emotional. I noticed that “veins”/”lines” were frequently described.

THIRD READING

I focused mostly on creating the outline. I numbered each section and noted when a detail referenced another detail. I began to feel that it was written beginning to end, initially, then edited repeatedly, and probably that there were some scenes prior to where the book currently begins, and after where the book ends, that were deleted, because the references were both forward and backward and sometimes seemed to reference things before page one. I think I also made the list of characters and began noticing that each character—and each of the three romantic relationships—seemed to have their own “plot,” or movement, or concern, that was consistent and “not forgotten” throughout the book.

While making the outline I discerned that the book is set at the beginning of Summer, over seven days, which surprised me, I think. It seems obvious, now, to some degree, that it was set over days, because the same pineapple—first referenced in [2], as “an old pineapple” whose “cut end had gone black, completely rotten”—is referenced throughout and in the last sentence of the book before the one-page “Letter to Lilly.”

I felt like I was studying a person, in that I knew some things might not seem coherent from certain perspectives, with limited information, but was able to assume that from a large enough perspective, with enough information, everything would seem coherent, which increased my interest in the book. Similar to if I saw something anomalous on the street, like a neon-green llama, I wouldn’t lose interest in concrete reality, but would likely have increased interest, because I would assume there was an ultimately coherent—and probably interesting, funny, or emotional—reason why the llama was there and why it was neon-green.

FURTHER READINGS

I noticed that the narrator (Ryu remembering the book’s events), as opposed to the character (Ryu living the book’s events) seemed notably focused on the relationships and emotional states of other characters in the book—for example in [3] Ryu is distracted and doesn’t ask Reiko any questions about her “specimen book,” despite her seeming very interested in it and seeming to want to talk about it and even saying she wants to show it to him. Because the chapter ends with “Reiko just stared at the rails,” and other details, maybe just that Ryu ignoring Reiko was shown but not explained, I felt that the narrator either felt some kind of sympathy with Reiko or simply viewed Reiko being neglected as interesting and worth conveying objectively, which made me feel emotional.

I noticed that most scenes with social interactions had instances where people were ignored, and that the narrator seemed to convey these instances—or they were conveyed as a side-effect of describing social situations with equal and accurate focus on each person, which naturally reveals that some people were ignored—but did not comment on them. I felt that people seemed to like Ryu because he seemed to be the most observant and socially aware, and least antagonistic, maybe, character in the book. The narrator, calmly describing things, seemed like an even more observant and socially aware version of Ryu, which was calming to read, I think.