Songbirds, Snakes, Psychopaths: How Narcissists Pursue Love and Power In The Hunger Games

From the newly released prequel The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes to The Mockingjay, both the Hunger Games movies and books have captivated modern audiences who often recognize chilling parallels between Suzanne Collins’ dystopian world to real life events. Panem may be a fictional world, but it grants us devastating insights into the ways love,…

This article contains spoilers for the Hunger Games book series and movies.

From the newly released prequel The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes to The Mockingjay, both the Hunger Games movies and books have captivated modern audiences who often recognize chilling parallels between Suzanne Collins’ dystopian world to real life events. Panem may be a fictional world, but it grants us devastating insights into the ways love, revolution, resistance, and war play out in real life. Here are some of the most crucial lessons viewers learn about how narcissists and psychopaths view power, love, and the state of humanity throughout the book series and movies.

Love Is Viewed As Ownership And A War Tactic – There Is No Good Deed Unless It’s for Image

In the book The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Coriolanus Snow is an orphan of war who has sadistic and psychopathic tendencies – a young man who will do anything for money and power. The movie adaptation of the prequel grants Snow more moral ambiguity and paints him as possessing far more empathy and remorse than he actually does in the book. While Snow grows up in luxury, we witness him lose his wealth, family, and privilege as he struggles during the “dark days” of the first rebellion and vows to reclaim power and control at all costs. He blames his struggle on the rebels rather than the Capitol and his sadistic need to punish rebels becomes apparent in his rise to power. He uses his charm and good looks to finesse the system, even betraying his friend Sejanus to gain access to resources while feeling little to no remorse for his actions. Under the guidance of the malevolent Dr. Gaul, he learns more about human nature, military strategies, and taps into his darker personality traits. In fact, throughout the book, he is largely self-centered, unempathic, and entitled, doing good deeds only for the cameras or when it benefits him. He becomes infatuated with the Hunger Games tribute he mentors, Lucy Gray, who he eventually ends up trying to hunt down due to his own paranoia. In the books, Snow’s love is not about genuine care or empathy – as for most people with narcissistic or psychopathic tendencies, it is about loyalty, ownership, and possession. As we’ll discuss later, Lucy is an obsession – an object he wants to possess – rather than a genuine love interest.

This is the villain “origin story” that many readers want to know, yet it’s impossible not to compare Snow’s childhood to Katniss. Katniss, too, struggled as she grew up in the impoverishment of District 12 and fought to survive. Yet unlike Snow, she made the choice to pursue survival by protecting the ones she loved, whereas Snow grows up pursuing power to ensure that he would never have to work hard to survive again – even if it meant harming others, even the ones he claims to love, in the process.

It is especially terrifying to consider Snow’s childhood when we know from the prequel that Snow could have easily taken what he learned from his experiences of early struggle to benefit the greater good and help end the Hunger Games before they continued. Instead, he chose to use what he learned about human nature and survival to design future games that would allow him the sadistic pleasure of watching others he considered “beneath him” fight to survive. Rather than trying to save people from the same suffering he endured, this trajectory exposes how he weaponizes his trauma as justification for horrific crimes against humanity.

In matters of love as well as friendship, the book reveals how narcissists and psychopaths use the appearance of love as a means to an end, rather than as a powerful motive for deeper connection. In contrast to how the “rebels” throughout the Hunger Games series are motivated by love to survive (illustrated most powerfully in Katniss’ love for Peeta and Primrose, causing her to take on many risks and sacrifices to protect her tribe) and wage a revolution against the Capitol to regain the integrity and freedom of their people, “love” in the hands of narcissists and psychopaths becomes just another war tactic in the rise to power. Any casualties, no matter how horrific, are considered insignificant and “necessary” to meet one’s goals.

A Young Psychopath’s Rise to Power: Differences in The Book and Movie

As we circle back to the past, in the prequel to the rest of the Hunger Games series, we gain more insight to the way psychopaths view power and love through the eyes of the man who significantly contributed to the current design of the Hunger Games – the future head of the Capitol, Coriolanus Snow, as a young man “in love.” As a result of the Rebellion leaving him without his family and without money, Coriolanus is met with the responsibility of rising to power as an adult – namely, by pursuing the Plinth Prize which will secure him the scholarship to pursue his education and bring respect back to his family name. In the 10th annual Hunger Games, he is assigned to mentor District 12 female tribute Lucy Gray Baird, whose spunk, rebelliousness, and talent mesmerizes him. He enjoys seeing Lucy plant a snake down the dress of the mayor’s daughter (who likely arranged for Lucy to be reaped into the Games), and rejoices in her singing: he recognizes that her musical talent will allow her to garner support during the games. Throughout both the book and film, we see both of them save each other’s lives as part of their “love story.” While the movie leaves it up to the viewer’s interpretation, the book features insight into what Coriolanus is really thinking about Lucy. His perspective of the relationship is far more transactional as he often considers how Lucy benefits him by boosting his image or bringing positive attention his way. He also thinks of Lucy as “his,” something to own rather than a person he loves. For example, consider the following exchange in the book:

“Well that’s it then, I saved you from the fire, and you saved me from the snakes. We’re responsible for each other’s lives now.”

“Are we?” he asked.

“Sure,” she said. “You’re mine and I am yours. It is written in the stars.” He leaned over and kissed her, flushed with happiness, because although he did not believe in celestial writings, she did, and that would be enough to guarantee her loyalty.

In this particular moment in the book, Snow is enthusiastic about Lucy’s belief in being destined and fated lovers not because he himself believes in the inevitability of their love but because such a spiritual belief will secure her loyalty and devotion to him. Lucy also notes in the book that she believes there is an “inherent goodness” in human beings, a belief that will be weaponized against her by Coriolanus. Coriolanus, on the other hand, views his own acts of betrayal and evil (such as making the “tough decision” to get his friend Sejanus killed by recording his rebel plans with a jaberyjay and sending it to the Capitol) as justifiable. In the books, his contempt and jealousy of his wealthy friend Sejanus are more evident, and he only puts on the mask of friendship in order to gain access to his family’s resources, feeling little to no remorse for doing so. Yet even in the movie, his betrayal of Sejanus as a devotee of the Capitol’s rigid rules is chilling. Even after Sejanus is executed, Coriolanus continues to benefit as he becomes heir to the Plynth family and conceals the true nature of Sejanus’ death. This is true to life when it comes to the mindset of narcissists and psychopaths: they view friendships and relationships as pathways to potential power, not connection. Everyone is an object to be strategically used to “win.”

Snow’s Legacy of Malice and Sadism in Catching Fire and Mockingjay

Before we delve deeper into the prequel, we first need to pause and remember how Snow’s burgeoning ideas advance into a tyrannical regime which illustrates the price that is paid when narcissists and psychopaths rise to power in the rest of the series. Fast-forwarding to the “future,” this is demonstrated palpably in President Snow’s terrifying tactics throughout the Hunger Games series to subdue rebellion and threaten the rebels with the loss of their loved ones. Civilians are starved as they are exploited, cutting off access to food and resources even as they perform labor to provide for the wealthy Capitol. Rebels are painted as “The Other,” and uprisings in the Capitol are met with cruel and unusual punishment. Hospitals are bombed as rebellion continues. The Hunger Games forces the most innocent and vulnerable – young children between the ages of 12 and 18 – to fight to the death for survival, killing all but one as “victor.” Snow regularly poisons his political enemies, even going so far as to drink poison himself to take the antidote right after to fool them, which leaves open sores on his mouth he covers with the scent of white roses. Snow’s need to maintain power at all costs and the sadistic nature of the Hunger Games is nothing short of the violence psychopaths are capable of.

The Role of Empathy In the Movie Grants Snow More Moral Complexity Than He Has

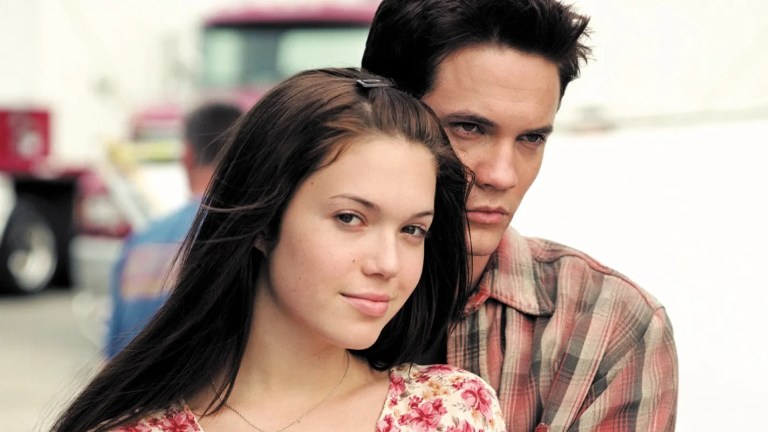

In the movie adaptation of the prequel, Snow (played by Tom Blyth) seems visibly concerned and empathic toward Lucy Gray’s (played by Rachel Zegler) plight and fight for survival in the games, and this concern seems to go beyond just wanting to win the prize money for having the winning tribute or restoring his family’s prestige – he seems (at least to movie viewers) to be genuinely in love with Lucy as a person. The romance and chemistry between them on screen are sizzling, and this ensnares viewers into believing in their love story. In the books, while he is certainly entranced by Lucy, his helpfulness is largely performative based on her potential to help him win the prize money – and he basks in the positive attention that having a tribute like Lucy Gray gives him. As he goes out of his way to mentor her in unconventional ways – joining her at the Capitol zoo, bringing her a white rose when they first meet (a unique symbol that will be especially significant throughout his journey to becoming a dictator in the Hunger Games), and stroking her cheek while she cries, viewers see a “softer side” to Snow whose feelings for Lucy only strengthens when she goes out of her way to save his life. In the book, young Snow is a less of a morally ambiguous character. His inner monologue reveals that he does not “love” Lucy the way he seems to love her in the movies – instead, it reveals that he objectifies her and wants to “possess” her, often obsessing over whether she is still interested in her former partner, Billy Taupe with a fixation that borders on pathological. Given this context, the movie scenes of him giving Lucy the white rose seem less romantic and more like love bombing and manipulation. He presents her with a gift not because of true compassion or kindness, but because he needs Lucy on his side in order to win the prize money. One of the most powerful ways to do this is by showering Lucy with attentiveness and convincing her that he will take care of her. One could argue that because she becomes a “useful” object to him, that is why he appears to be so enamored with her. She is enigmatic, talented, resourceful, rebellious yet seemingly loyal: the perfect catnip that draws a psychopath in for potential exploitation.

These tendencies are far more striking in the book through Snow’s inner monologue, as Snow often has a personal motive for everything he does: for example, in the movie, both he and his friend Sejanus plot together to give the tributes food. There is a seemingly altruistic element to their motivation in the movies, but in the books, Coriolanus only joins Sejanus in this generous act because he doesn’t want Sejanus to have the spotlight and thinks it will boost his image for reporters. In the movie adaptation of the prequel, Coriolanus Snow is depicted as more of a morally conflicted character who shows remorse and even has the capacity for love – the question of whether he is a budding psychopath or a man who descends into evil after life’s circumstances and seeming betrayals is still up in the air when we are unable to “see” or hear his inner monologue on screen. Instead, we are led to believe that as Lucy abandons him due to her own fears that he “chooses” the side of evil because he is heartbroken. However, in the books it is made clear that these malignant tendencies always existed within him and were just given the opportunity to grow.

Snow and Alma: Psychopaths in Power and Two Sides of the Same Coin

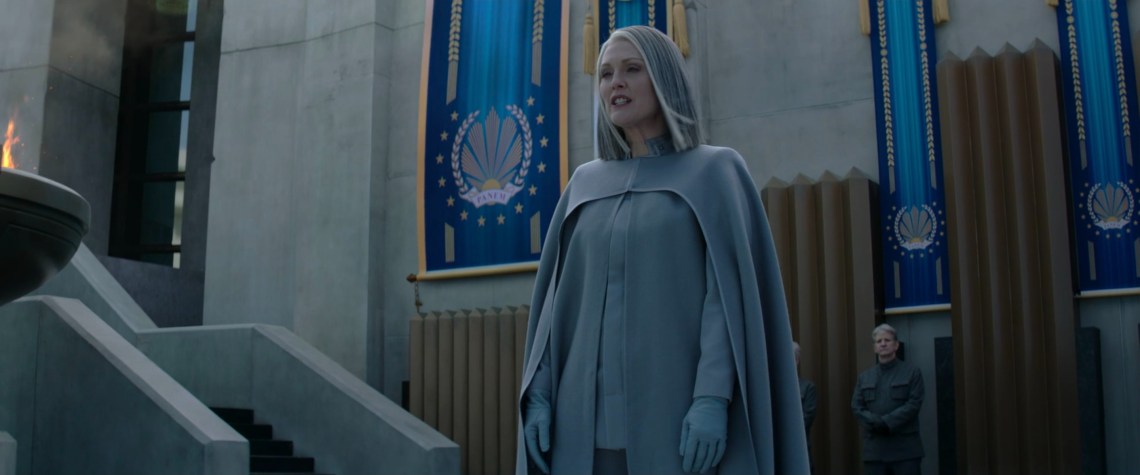

A similarly sadistic nature is perhaps even more frighteningly exhibited in President Alma Coin of District 13, who uses the guise of spearheading “revolution” to rise to power in The Mockingjay and become interim president of Panem. Unlike Snow whose genuine agendas are less concealed in the series, President Coin of District 13 is more covert in concealing her true malice – much like any female psychopath in the pursuit of power. We do not get any information about President Coin’s past in the prequel or why she is the way she is, but it’s clear Snow has met his match in the series. Similar to the way the Capitol scapegoats innocent children by reaping them into the Hunger Games as punishment and entertainment for the wealthy masses, Coin is not above bombing and killing innocent children like Primrose just to ensure Katniss stays out of power so she can reign. She forces Katniss to undergo a long “PR campaign” to fuel the fires of rebellion as The Mockingjay. She weaponizes her own tears, feigning remorse and integrity when Katniss is seemingly killed, just to elevate herself into a position of power and kill Katniss’ sister – these malignant tactics are astonishingly cruel but true to life. It is especially accurate to the ways psychopaths use pity ploys and seemingly altruistic purposes to carry out their hidden agendas.

Coin presents herself as the empathic leader of a revolution to release the districts from tyranny, but while this revolution is needed, her true motive is power, and she is also the tyrant she warns the world about.

The ruthlessness and lack of empathy with which psychopaths and narcissists operate to get to the top, along with weaponizing tactics like gaslighting and smear campaigns which both Coin and Snow engage in, swaying the public to view each other as the enemy while dehumanizing the most innocent and vulnerable civilians, are accurate depictions of the ways powerful psychopathic leaders engage in not just literal war but also psychological warfare.

Katniss: A Symbol for Revolution and The Real Revolutionary

On the other hand, Katniss contrasts these psychopathic leaders as the true leader of the revolution with her genuine empathy and love for others. Katniss and Peeta represent the “good” of humanity, and the promise of revolution. Not only is she a potent symbol that carries and inspires the citizens of Panem through the devastation of war, she makes countless sacrifices to save the people she loves and even the people she does not know. She also pushes Snow back to “memory lane” as he is forced to remember his young love, Lucy Gray, with Katniss’ haunting renditions of her songs and the symbol of the mockingjay. Her love for her little sister Prim causes her to volunteer as tribute and take her place when Prim is chosen in the reaping for the Hunger Games. She risks her life to save Peeta during the games, as well as to try to keep one of the younger tributes, Rue, safe. Her love for Peeta visibly engages Snow in the games, as he is both fascinated and resentful of the young woman who reminds him of Lucy Gray’s supposed betrayal. She is ultimately the one who ends the tyranny of not only one psychopath in power, but two, preventing history from repeating itself in President Coin’s destructive leadership and ending the Hunger Games for good. In one of the most powerful movie moments in history, she appears to point her bow and arrow at President Snow, only to kill President Coin instead, as she realizes that some of the most dangerous people in power are the ones who mask themselves as saviors. Perhaps what tips her off aside from Snow disclosing Coin’s motives is that President Coin isn’t above using the children of the Capitol to continue the Hunger Games – ultimately not deviating from Snow’s cruel legacy – as a display of power and revenge. Regardless, Katniss’ execution of Coin still leads to Snow’s demise as well as the crowd is free to launch themselves on him.

Rather than portraying young Snow as someone with outright blatantly malignant tendencies, the movie is far more subtle in tracking his trajectory to his reign of terror, emphasizing how his family circumstances of current struggle after Rebellion in the Capitol have left the once privileged Snow family without resources and caused him to use other means to gain power and control. This more subtle escalation leads to a more jarring experience for viewers when Snow starts betraying the people who’ve stuck by him and even killing people with more ruthlessness and rationalization. Viewers are led to question whether his future ruthlessness was deepened by Lucy’s “betrayal” of Coriolanus when she realizes that he played a hand in Sejanus’ death and may even kill her too out of fear of exposing him. Yet book readers are given the context that Coriolanus was always a budding predator who had a choice – and he chose the path of being a tyrant. Thankfully, Lucy escapes before he can harm her, realizing theirs is not a fated love story but a twisted tale of her becoming the latest fixation of a psychopath – one that will do anything for the pursuit of power.