The Genius Inside You: Unlocking the Brain’s Drive To Mastery

If all of us are born with an essentially similar brain, with more or less the same configuration and potential for mastery, why is it then that in history only a limited number of people seem to truly excel and realize this potential power?

If all of us are born with an essentially similar brain, with more or less the same configuration and potential for mastery, why is it then that in history only a limited number of people seem to truly excel and realize this potential power?

The common explanations for a Mozart or a Leonardo da Vinci revolve around natural talent and brilliance. How else to account for their uncanny achievements except in terms of something they were born with? But thousands upon thousands of children display exceptional skill and talent in some field, yet relatively few of them ever amount to anything, whereas those who are less brilliant in their youth can often attain much more. Natural talent or a high IQ cannot explain future achievement.

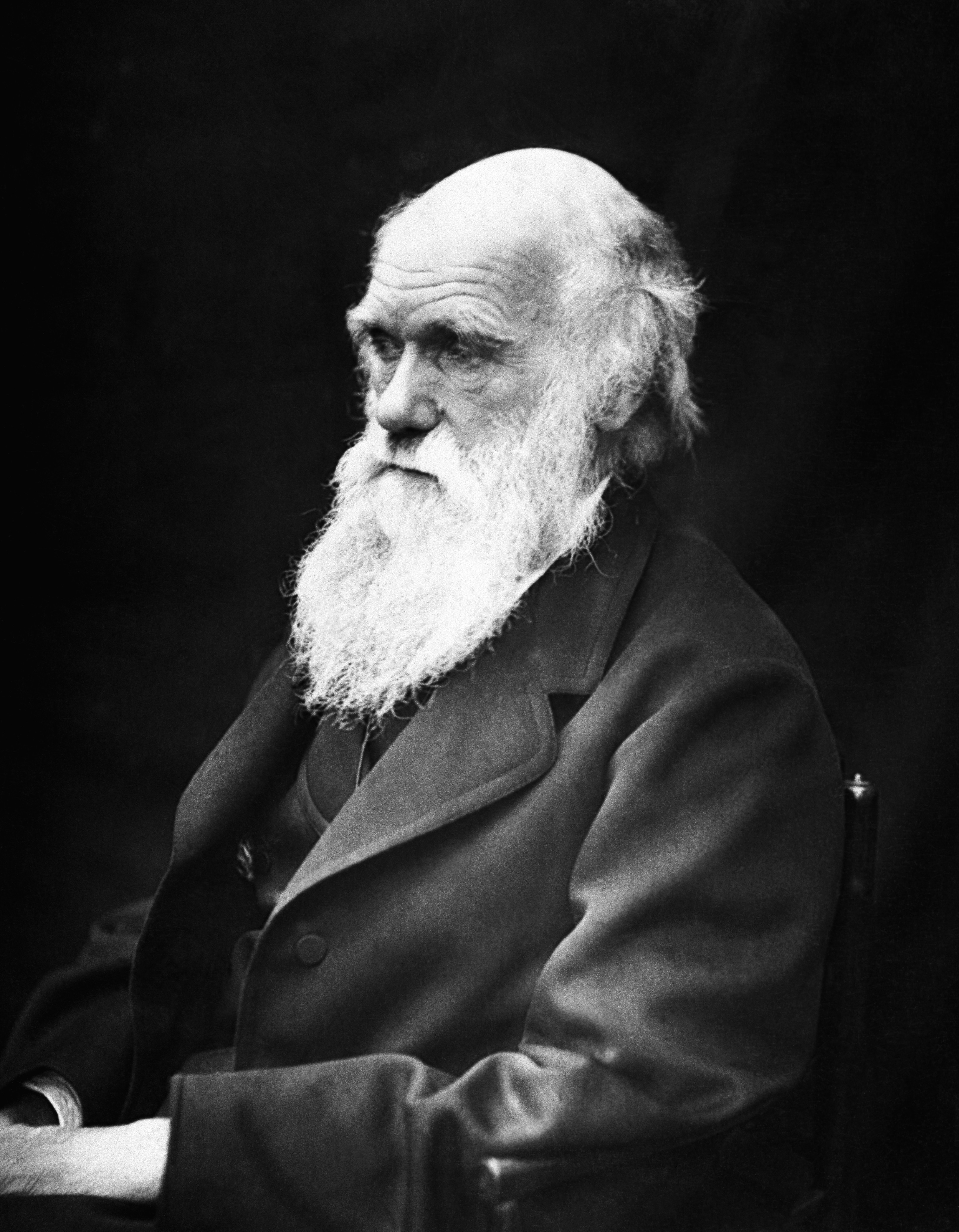

As a classic example, compare the lives of Sir Francis Galton and his older cousin, Charles Darwin. By all accounts, Galton was a super-genius with an exceptionally high IQ, quite a bit higher than Darwin’s (these are estimates done by experts years after the invention of the measurement). Galton was a boy wonder who went on to have an illustrious scientific career, but he never quite mastered any of the fields he went into. He was notoriously restless, as is often the case with child prodigies.

Darwin, by contrast, is rightly celebrated as the superior scientist, one of the few who has forever changed our view of life. As Darwin himself admitted, he was:

a very ordinary boy, rather below the common standard in intellect. . . .I have no great quickness of apprehension. . . .My power to follow along and purely abstract train of thought is very limited.

Darwin, however, must have possessed something that Galton lacked.

In many ways, a look at the early life of Darwin himself can supply an answer to this mystery. As a child Darwin had one overriding passion— collecting biological specimens. His father, a doctor, wanted him to follow in his footsteps and study medicine, enrolling him at the University of Edinburgh. Darwin did not take to this subject and was a mediocre student. His father, despairing that his son would ever amount to anything, chose for him a career in the church. As Darwin was preparing for this, a former professor of his told him that the HMS Beagle was to leave port soon to sail around the world, and that it needed a ship’s biologist to accompany the crew in order to collect specimens that could be sent back to England. Despite his father’s protests, Darwin took the job. Something in him was drawn to the voyage.

Suddenly, his passion for collecting found its perfect outlet. In South America he could collect the most astounding array of specimens, as well as fossils and bones. He could connect his interest in the variety of life on the planet with something larger—major questions about the origins of species. He poured all of his energy into this enterprise, accumulating so many specimens that a theory began to take shape in his mind. After five years at sea, he returned to England and devoted the rest of his life to the single task of elaborating his theory of evolution. In the process he had to deal with a tremendous amount of drudgery—for instance, eight years exclusively studying barnacles to establish his credentials as a biologist. He had to develop highly refined political and social skills to handle all the prejudice against such a theory in Victorian England. And what sustained him throughout this lengthy process was his intense love of and connection to the subject.

The basic elements of this story are repeated in the lives of all of the great Masters in history from Henry Ford to Mozart: a youthful passion or predilection, a chance encounter that allows them to discover how to apply it, an apprenticeship in which they come alive with energy and focus. They excel by their ability to practice harder and move faster through the process, all of this stemming from the intensity of their desire to learn and from the deep connection they feel to their field of study. And at the core of this intensity of effort is in fact a quality that is genetic and inborn—not talent or brilliance, which is something that must be developed, but rather a deep and powerful inclination toward a particular subject.

This inclination is a reflection of a person’s uniqueness. This uniqueness is not something merely poetic or philosophical—it is a scientific fact that genetically, every one of us is unique; our exact genetic makeup has never happened before and will never be repeated.

This uniqueness is revealed to us through the preferences we innately feel for particular activities or subjects of study. Such inclinations can be toward music or mathematics, certain sports or games, solving puzzle-like problems, tinkering and building, or playing with words.

With those who stand out by their later mastery, they experience this inclination more deeply and clearly than others. They experience it as an inner calling. It tends to dominate their thoughts and dreams. They find their way, by accident or sheer effort, to a career path in which this inclination can flourish. This intense connection and desire allows them to withstand the pain of the process—the self-doubts, the tedious hours of practice and study, the inevitable setbacks, the endless barbs from the envious. They develop a resiliency and confidence that others lack.

In our culture we tend to equate thinking and intellectual powers with success and achievement. In many ways, however, it is an emotional quality that separates those who master a field from the many who simply work at a job. Our levels of desire, patience, persistence, and confidence end up playing a much larger role in success than sheer reasoning powers. Feeling motivated and energized, we can overcome almost anything. Feeling bored and restless, our minds shut off and we become increasingly passive.

In the past, only elites or those with an almost superhuman amount of energy and drive could pursue a career of their choice and master it. A man was born into the military, or groomed for the government, chosen among those of the right class. If he happened to display a talent and desire for such work it was mostly a coincidence. Millions of people who were not part of the right social class, gender, and ethnic group were rigidly excluded from the possibility of pursuing their calling. Even if people wanted to follow their inclinations, access to the information and knowledge pertaining to that particular field was controlled by elites. That is why there are relatively few Masters in the past and why they stand out so much.

These social and political barriers, however, have mostly disappeared. Today we have the kind of access to information and knowledge that past Masters could only dream about. Now more than ever, we have the capacity and freedom to move toward the inclination that all of us possess as part of our genetic uniqueness. It is time that the word “genius” becomes demystified and de-rarefied. We are all closer than we think to such intelligence. (The word “genius” comes from the Latin, and originally referred to a guardian spirit that watched over the birth of each person; it later came to refer to the innate qualities that make each person uniquely gifted.)

Although we may find ourselves at a historical moment rich in possibilities for mastery, in which more and more people can move toward their inclinations, we in fact face one last obstacle in obtaining such power, one that is cultural and insidiously dangerous: The very concept of mastery has become denigrated, associated with something old-fashioned and even unpleasant. It is generally not seen as something to aspire to. This shift in value is rather recent, and can be traced to circumstances peculiar to our times.

If we don’t try too much in life, if we limit our circle of action, we can give ourselves the illusion of control. The less we attempt, the less chances of failure. If we can make it look like we are not really responsible for our fate, for what happens to us in life, then our apparent powerlessness is more palatable. For this reason we become attracted to certain narratives: it is genetics that determines much of what we do; we are just products of our times; the individual is just a myth; human behavior can be reduced to statistical trends.

The idea that they might have to expend much effort to get what they want has been eroded by the proliferation of devices that do so much of the work for them, fostering the idea that they deserve all of this—that it is their inherent right to have and to consume what they want. “Why bother working for years to attain mastery when we can have so much power with very little effort? Technology will solve everything.” This passivity has even assumed a moral stance: “mastery and power are evil; they are the domain of patriarchal elites who oppress us; power is inherently bad; better to opt out of the system altogether,” or at least make it look that way.

If you are not careful, you will find this attitude infecting you in subtle ways. You will unconsciously lower your sights as to what you can accomplish in life. This can diminish your levels of effort and discipline below the point of effectiveness. Conforming to social norms, you will listen more to others than to your own voice.

Before it is too late you must find your way to your inclination, exploiting the incredible opportunities of the age that you have been born into. Knowing the critical importance of desire and of your emotional connection to your work, which are the keys to mastery, you can in fact make the passivity of these times work in your favor and serve as a motivating device in two important ways.

First, the world is teeming with problems, many of them of our own creation. To solve them will require a tremendous amount of effort and creativity. Relying on genetics, technology, magic, or being nice and natural will not save us. We require the energy not only to address practical matters, but also to forge new institutions and orders that fit our changed circumstances. We must create our own world or we will die from inaction

Second, you must convince yourself of the following: people get the mind and quality of brain that they deserve through their actions in life. Despite the popularity of genetic explanations for our behavior, recent discoveries in neuroscience are overturning long-held beliefs that the brain is genetically hardwired. Scientists are demonstrating the degree to which the brain is actually quite plastic—how our thoughts determine our mental landscape. They are exploring the relationship of willpower to physiology, how profoundly the mind can affect our health and functionality.

People who are passive create a mental landscape that is rather barren. Because of their limited experiences and action, all kinds of connections in the brain die off from lack of use. Pushing against the passive trend of these times, you must work to see how far you can extend control of your circumstances and create the kind of mind you desire—not through drugs but through action.

Unleashing the masterful mind within, you will be at the vanguard of those who are exploring the extended limits of human willpower.

In moving toward mastery, you are bringing your mind closer to reality and to life itself. Anything that is alive is in a continual state of change and movement. The moment that you rest, thinking that you have attained the level you desire, a part of your mind enters a phase of decay. You lose your hard-earned creativity and others begin to sense it. This is a power and intelligence that must be continually renewed or it will die. ![]()