Netflix’s ‘Weak Hero Class 2’ Makes A Brilliant Case For Writing TV Like A 19th Century Novel

Weak Hero Class 2 is a work of art.

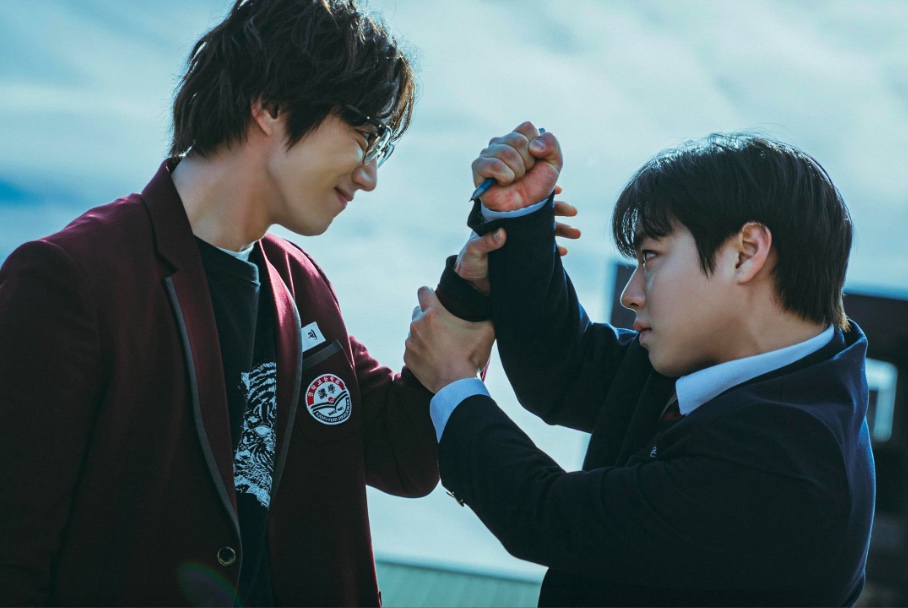

I know that seems like a lot for what appears on the surface to be a series about teenage boys beating the crap out of each other, but it impressed me beyond my wildest expectations, and has earned my full endorsement.

I was uncertain where the series would go after such a cathartic ending to its first season. I wasn’t entirely convinced Si-Eun’s story required continuation for reasons that weren’t commercial, or merely a natural desire for our favorite stories to continue on forever, but sometimes a good ending is exactly what elevates one to “lifelong favorite” status. Weak Hero Class 1 has those bones. It was fully developed and perfectly packaged. It worked as a standalone story.

However, I discovered that the first season story arc is merely the prequel of the Web Toon which lends the series its IP. These online comics are serialized weekly, on platforms that offer aspiring creators the opportunity to self-publish their own stories for a global audience. Weak Hero‘s author, Seopass, started the series as a side-hustle while maintaining a separate full-time job.

We’re talking about a kind of writing that is way more economically accessible than pitching a script directly to a major streamer like Netflix, and the episodic nature of production shares much more with Dickens, Dostoevsky, and Dumas’ greatest literary works, which were originally published weekly in magazines.

While we’ll never know exactly how much any of the greats “winged it” from week to week, their texts certainly imply a certain level of planning to juggle character development and plot lines across stories of significant length. It’s a bit different than writing a sitcom pilot and waiting for it to be picked up, or an eight-episode miniseries with an open-ended finale that future-proofs your work against the dreaded cancellation axe.

In the case of Weak Hero Class 2, a plotline with forethought pays off. It doesn’t ramble aimlessly looking for new landmarks or purpose. It doesn’t sensationally or gratuitously heighten previously themes of violence just for shock value or lack of material. It picks up exactly where Si-Eun left off, wracked by his own guilt over his inability to save Su-Ho. Helpless, with no way to bring his friend out of a coma, and exiled from a school where he was never the bully to begin with.

We get another glimpse at the endless bully-victim food-chain, where there is always someone else preying on the people enacting violence on others, but Si-Eun’s experience and sense of loss brings him to these scenarios with new found perspective.

He longs for friendship, but keeps peers at an arms length to avoid the kind of retaliation and provocation that landed Su-Ho in the hospital. He knows battles aren’t best fought alone, but still feels the guilt is his alone to bear. And finally, he’s learned how important public perception is to a bully’s ability to terrorize an entire student population, and uses that to his advantage.

While we’re examining all of this in the context of Si-Eun’s world, that microcosm becomes the stand-in for larger questions about adolescence and male loneliness on a global scale. Its rich, emotional depth provides thoughtful and introspective solutions. It’s gruesome, but hopeful. And most importantly, it’s a story that needed to be told.