Eight Ways Twilight is Better Than Real Life

The Twilight series of books/films is widely perceived to be bad, sexist and potentially in possession of a ‘Mormon agenda,’ even by people who have not consumed any of the books or films nor are able to articulate what a ‘Mormon agenda’ is besides ‘having a ton of wives’ or ‘not having sex’ or ‘having…

The Twilight series of books/films is widely perceived to be bad, sexist and potentially in possession of a ‘Mormon agenda,’ even by people who have not consumed any of the books or films nor are able to articulate what a ‘Mormon agenda’ is besides ‘having a ton of wives’ or ‘not having sex’ or ‘having a ton of babies while being really nice to people.’

The rationale for the determination of the series as ‘sexist’ [bluntly put by the UK independent as ‘sick-makingly sexist’] is that heroine Bella Swan is fundamentally incapable of doing anything on her own besides getting into situations that require her rescue. She spends most of the story flinching, falling down, whining/crying, cleaning and obeying dudes.

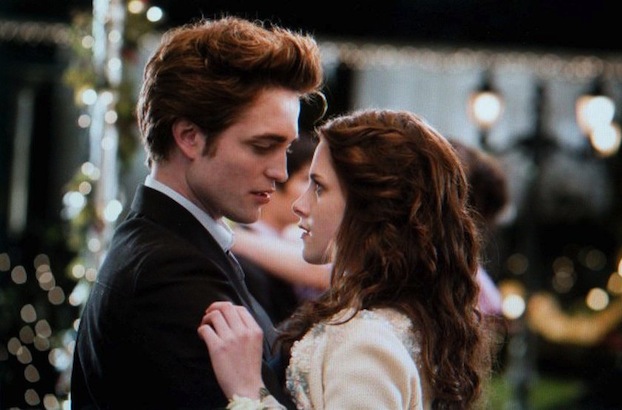

When Bella meets sparkling vampire Edward he pretty much becomes her whole life, to where she disconnects from her old friends; platonic males become contentious for Edward while Bella abruptly loses interest in her ‘galpals.’ She starts lying to her long-suffering single father because Edward is the only thing she cares about. Then when Edward leaves due to a melodramatic misunderstanding Bella is totally inconsolable and engages in high-risk behavior until she meets Jacob, some other dude who likes her, and only under his attention does she begin to act somewhat emotionally stable again.

From there, the entire storyline revolves around saving Bella from evils including her own desire to become a vampire, a goal to which everyone who cares about her is firmly opposed. Edward is basically like ‘you think you know what’s good for you but I do and you don’t,’ and his attitude pervades all of Bella’s decisions from wanting to still hang out with Jacob to whether or not she should visit her mom or marry Edward or have sex with him [he holds the latter over her head to get her to do the former, essentially].

So there is much logical ‘public backlash’ about how Bella is a bad heroine, a ‘negative female stereotype’ and how despite theoretically ‘promoting a message of chastity,’ the Twilight franchise is a ‘bad influence’ on young girls or something. However, the brand remains explosively popular not only among young girls but among actual adult women of all ages.

To understand why, the fantasies presented in the story bear further examination. The following examples present ‘what happens to in Twilight’ versus ‘what happens in a woman’s real life’ in a fashion that will hopefully prove illuminating to readers of all kinds.

1.

In Real Life: I feel mousy, self-conscious, clumsy and insecure. I will spend high school being awkwardly groped at sporting events by boys for whom I have no particular affinity, and then after I reject traditional standards of beauty for myself I will marry a man who mostly stays out of my way and with whom I struggle to enjoy sexual chemistry.

In Twilight: I feel mousy, self-conscious, clumsy and insecure. I am the perfect partner for a heart-stoppingly gorgeous supernatural super-strong man who will live forever and love me forever until time stops.

2.

In Real Life: Now that I have a boyfriend I don’t really feel like seeing my shitty friends anymore and when I am finally overcome with guilt for completely blowing them off I make a half-hearted attempt to reach out and they can no longer make time for me, resentful that I have been too absorbed with my relationship to feign interest in them.

In Twilight: My gorgeous supernatural partner has invited me into his world and I no longer need anyone or anything else. My family and friends hang around expressing their concern until I feel like acknowledging them again.

3.

In Real Life: My gorgeous, powerful boyfriend enjoyed my company for a while, but when I became needy he started to think about how every other girl in school also is attracted to him and given that he has lived for a couple centuries and will live forever he thought about seeking someone more ‘on his level.’

In Twilight: Despite my lack of discernible ‘special’ traits, my gorgeous, powerful boyfriend maintains his eternal devotion to me and is demonstrably suicidal when separated from me.

4.

In Real Life: My boyfriend leaves me inexplicably, probably to have an affair with someone else or because I was too demanding or otherwise not good enough. I am never able to process or understand the breakup.

In Twilight: My boyfriend leaves me inexplicably, but I later learn he was simply trying to ‘protect’ me and suffered immensely in exactly the same ‘wrenching’ fashion as I. We reunite and he promises never to abandon me again.

5.

In Real Life: The hot guy on whom I relied when I had problems with my boyfriend is pissed at me for leading him on. He decided he had too much self-respect to stand around watching me make out with my boyfriend and that he had better things to do with his life than spend it waiting around on me. We are no longer friends because when he got over the heartbreak he felt used and misled.

In Twilight: The hot guy on whom I relied when I had problems with my other hot guy will always love me, being my friend forever even though I went back to my boyfriend. He loved me for its own sake, not because he was expecting something back. If things do not work out with my boyfriend, he will still be waiting.

6.

In Real Life: My boyfriend disabled my car to prevent me from seeing a male friend. My friends, family and I are creeped out by this controlling behavior that could portend future abuse.

In Twilight: I am a prize at the core of a centuries-old war between two supernatural races. These two men are fighting over me and both have my well-being at heart.

7.

In Real Life: I really enjoy the emotional rapport that my boyfriend and I have and yet I feel he is pressuring me to be more sexual than I would otherwise prefer. I often wonder what portion of our relationship is explained by his physical interest in me, and fear being ‘used for sex.’ As a result, using my sexuality is the only time I feel assured of my power in any interaction with men, but I must be cautious not to push it too far or else I must be responsible for their reactions.

In Twilight: Even when I feel ready for sex and would like to do it with my boyfriend, he resists, telling me it is a sacred thing we should do when we are married and he loves me too much to place my virtue at risk. My boyfriend encourages me to use self-restraint and blames himself for his response to my body.

8.

In Real Life: I have a confusing and painful future full of loneliness, indecision and unwanted responsibility to look forward to when I graduate high school.

In Twilight: I have an eternity of sparkling, great sex, lying in fields and gamboling in the woods with my hot boyfriend who will love me until the end of time to look forward to when I graduate high school.

The preceding examples make it clear how appealing the impossible fantasy presented by Twilight is in particular to women who have been told they must be particularly strong, independent and emotionally/sexually responsible. The atmosphere of Twilight is almost constantly ‘threatening’ and/or ‘wrenchingly melodramatic’, as Bella is torn between two loves, requiring protection from initially unknown but rapidly-gathering dangers and yet completely reliant on impossibly strong men to save her. She seems to want nothing else but to be loved and protected.

It would seem this is an extreme ‘escapist’ response to the complex pressures of being a woman. Jacob is secretly a werewolf and might suddenly ‘transform’ if he loses his temper, harming Bella if she is too close by at the time. Edward is so into the scent of Bella’s blood that he might ‘lose control’ and harm her if she has too much physical contact with her. In that regard, Twilight is a fiction that allows women to admit the primal fear of male anger and male sexuality, respectively.

These are fears that numerous women still harbor but feel they are not at liberty to admit lest they be judged‘bad feminists’. Twilight is a series that says it is ‘okay’, even beautiful or dramatic, to ‘want a man to take care of you’, to ‘feel helpless in a man’s world’ or ‘to need a man’s help to discover your identity’, which is tremendously relieving to some women. Others may not privately ascribe to those kinds of ideals but enjoy it in a quaint ‘fiction-of-the-past’ kind of way.

So it’s maybe ‘sexist’ or ‘presents a bad example’ but its popularity is highly illustrative of the fact that some women really don’t want to be ‘an example’. In a world where it’s fucking difficult to understand what it means to be a woman in a world where gender roles are being reasserted, Twilight’s ‘escapism’ is probably welcome to a lot of people who are tired of the fatiguing pendulum-swing between wanting a man who will ‘call you after sex’ and feeling like you shouldn’t ‘want a man’ at all, even if you want sex, or you should want to be loved or not want to be loved or you should be ‘in charge’ but then not want someone who isn’t ‘bringing anything to the table’ or you should ‘be treated like a queen’ or ‘be a king’ or whatever, it sucks and it is confusing but Twilight’s little world is very alleviating and makes a lot of sense.