‘Wonka’ Is No More Than a Hodgepodge of Far Better Musicals

By ![]() Josh Lezmi

Josh Lezmi

Wonka, penned as a prequel to the Gene Wilder-led Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, is yet another movie musical overwrought with big-budget CGI and intricately choreographed dance sequences that boast maximum dazzle yet minimal deft. Made-up words allow for juvenile rhyme schemes, which, even in the hands of Timothée Chalamet’s unwavering wide-eyed wonder and caffeinated charisma, grow stale and a tad irksomptious. (Not to mention, Wicked has already done the fictitious vocabulary shtick, and it did it with an “Ozian Glossararium” that was far more extensive and distinctive.)

The film’s every facet — each cartoony cantankerous crotch, despondent deserted daughter, silly song, and bold ballad feels plucked from a pot of peerless predecessors. What could have been an original and inspired origin story gives way to a derivative dance.

Mild spoiler warning for Wonka

Wonka follows a young “something of a magician, inventor, and chocolate maker” who travels to a city renowned for its chocolate shops. Yet, he comes up against the chocolate cartel — three candy shop owners in criminal cahoots who will do anything to squelch the ingenious competitor. They bribe the Chief of Police (with chocolate obviously) to “silence” him, yet with help from his fellow dwellers of Mrs. Scrubitt’s dastardy hotel — all of whom have been hoodwinked into servitude — Wonka sets out to bring his science-defying candy to the world.

The movie opens with Wonka on a ship, leaving behind what he knows to travel to a city where dreams come true. As he serenades audiences with “A Hatful of Dreams,” one can’t help but visualize Sweeney Todd’s far more contemplative “No Place Like London.” Wonka may be intended as a “light” movie, but so was the ‘71 classic, and that was far from short on depth — using its whimsical atmosphere to juxtapose the class inequality at the core. Wonka ultimately arrives in a city that feels like an amalgamation of multiple metropolitan areas — with sinister streets and opulent designer stores mere blocks apart. Yet, it is when we meet Olivia Colman’s Mrs. Scrubitt and her lowly business partner Bleacher (Tom Davis) that the film tramples right over the line of homage and into mimicry.

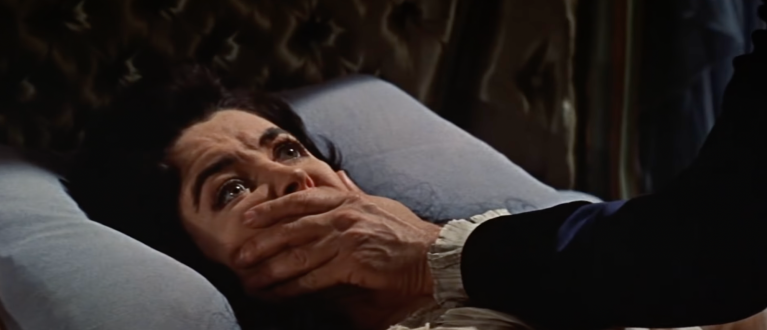

Colman’s character is equal parts Mrs. Trunchbull of Matilda, Madame Thenardier of Les Misérables, Mrs. Lovett of Sweeney Todd, and Miss Hannigan of Annie. However, in this case, she’s not the wife of the man charging “two percent for sleeping with the window shut,” she’s the mistress of the house charging extra for “warming your feet by the fire.” She also throws the young Noodle (the only child stuck in servitude) into the chicken coop when she defies her.

Colman plays the character with a devilish exaggeration. She’s digging her yellowed and crooked teeth into the villainy with a snide sense of misplaced superiority. Colman is scrumptious, yet the character is so blatantly imitative that she cannot reach the heights of her boozy and brash counterparts; she is merely banal. Though she is having a ton of fun, we’re losing the plot as we picture Carol Burnett singing “Little Girls.”

Though multiple musicals traipse into this movie’s foreground, Les Misérable seems to serve as the film’s narrative framework. When Wonka is tricked into living a life as a servant to Mrs. Scrubitt (to pay off the debts he unknowingly acquired), we meet the rest of the tricked gang, who introduce him to their way of life via the song “Scrub, Scrub.” They clean ‘em, they steam ‘em, they fold ‘em, and they “gotta do their time.” Multiple voices sing in unison, working their way through several verses, and always back to the words “Scrub, Scrub.” Spotify search “Look Down” from Les Misérables when you get a chance. Just like the characters at Javert’s mercy, these individuals are Mrs. Scrubitt’s prisoners.

Mrs. Scrubitt and Bleacher “look after” (a phrase used loosely here) Noodle, who doesn’t know what happened to her parents; she is the stand-in for Cosette, even singing a slow ballad titled “For a Moment,” in which she imagines a better life just “for a moment.” She can escape the agony of destitution when she daydreams. This is her “Castle on a Cloud.” And, as for Wonka, he is her Jean Valjean, who will do all in his power to save her from this wretched life, despite an implacable officer who aims to silence him (Keegan-Michael Key). Though Wonka is and never was a criminal like Jean Valean, and Key’s Chief of Police is not operating in unwavering service to legality at all costs, these moral grays would have been presumably too complex for the target demographic. That being said, the general premise is synonymous. Wonka is merely a brighter and more fantastical take digestible for the short-attention-spanned young-ins watching.

The narrative is not new. The goofiness inherent to the silly songs is not new. The sobriety inherent to the should-be tender moments feels forced and hurried. The movie has simply put a glossy finish over acclaimed works from the Great White Way. It Disney-ified the theatrical space it’s pulling from and, in doing so, also did a disservice to the Wonka character. Chalamet’s portrayal lacks Wilder’s erratic, not-to-be-trusted or understood disposition. He is sweeter than the candy he sells. And, maybe he’s simply yet to be jaded, but, if this is an origin story, should it not have provided a foundation for who he becomes? The two movies feel utterly disconnected, with no more than the tune “Pure Imagination” connecting them — a song that surfaces toward the end and is the film’s singular moving moment, which speaks more to the lasting impact of its predecessor than its own emotional resonance.

Wonka is currently playing in theaters.