Live-Action ‘The Little Mermaid’ Changes Lyrics to “Poor Unfortunate Souls” — For Better or for Worse?

By ![]() Josh Lezmi

Josh Lezmi

The live-action version of ‘The Little Mermaid’ alters some of the lyrics in “Poor Unfortunate Souls.” But, does Ursula (and the movie) benefit from this change? What inspired the adjustment?

It seems like yesterday that the live-action version of The Lion King defiled Scar, reducing his villainous anthem to a two-minute somewhat-rhythmic monologue. The song went from a rallying of the hyenas and a laid-out plan for a mutiny to an uninspired condemnation of Mufasa. Scar’s cunning and devious nature was replaced in favor of what? Mere anger and jealousy? His words seemed no longer “a matter of pride.”

The live-action Scar also lacked the superiority complex, condescending air of pretension, and flamboyant swagger inherent to the legacy of his animated counterpart. However, that’s a topic for another time, as we’re here to focus on lyrical alterations, not delivery. The lyric changes matched the new Scar’s darker persona and were likely penned to fit “modern sensibilities,” as is the argument concerning the changes to “Poor Unfortunate Souls.” Yet, the question is: do these lyrics benefit the song and the character, or reduce the Sea Witch to a pale imitation of her predecessor? That depends on perspective.

Breaking down the lyrical changes to “Poor Unfortunate Souls”

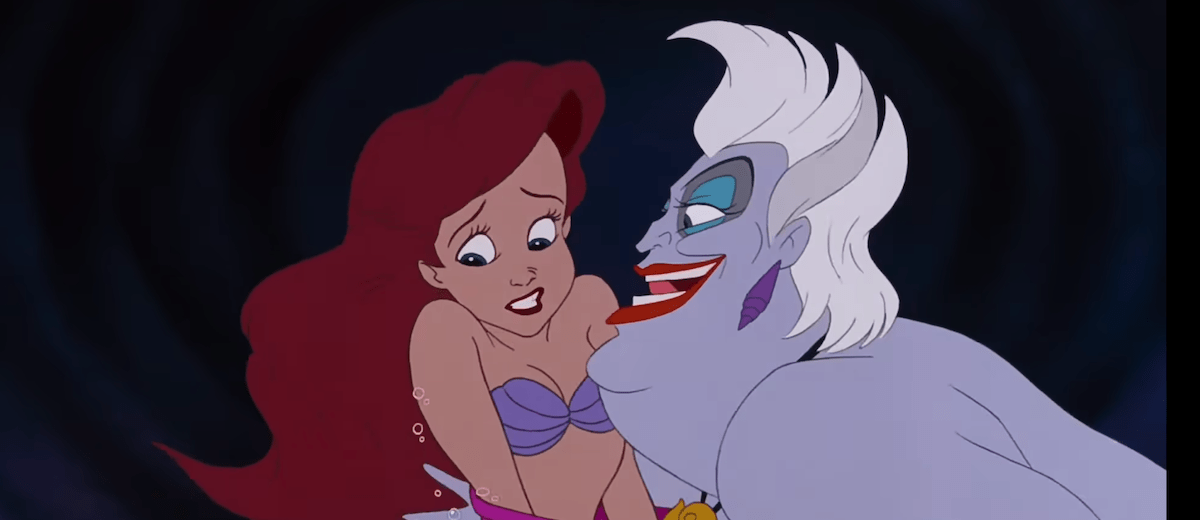

The original lyrics to “Poor Unfortunate Souls” contained a verse that is inherently misogynistic (more on this to come), as Ursula explains to Ariel why she won’t need a voice to snag her man. She sings:

“The men up there don’t like a lot of blabber

They think a girl who gossips is a bore!

Yet on land, it’s much preferred for ladies not to say a word

And after all dear, what is idle babble for?

Come on, they’re not all that impressed with conversation

True gentlemen avoid it when they can

But they dote and swoon and fawn

On a lady who’s withdrawn

It’s she who holds her tongue who gets a man”

In the new song, the verse is replaced with a line of dialogue. Ursula says:

“Fine then. Forget about the world above. Go back home to daddy and never leave again.”

The lyrical alterations focus on Ariel’s desire to see the world above, as opposed to reducing her earthly longings to a yearning for one man. Yet, it’s important to remember Ursula’s intentions when considering these lyrics, as well as her status as a villain turned cultural icon.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gi58pN8W3hY&t=98s

On the surface, the new lyrics to “Poor Unfortunate Souls” seem to dampen Ursula’s villainy

Lyricist and Composer Alan Menken explained to Vanity Fair why the lyrics were adjusted, stating:

“We have some revisions in ‘Poor Unfortunate Souls’ regarding lines that might make young girls somehow feel that they shouldn’t speak out of turn, even though Ursula is clearly manipulating Ariel to give up her voice.”

In his explanation, Menken arguably contradicts himself, noting that Ursula is “clearly manipulating Ariel” and, thus, her words should not be interpreted as fact, but rather as finesse. Ursula is bargaining with a youthful girl she knows she can outwit. Naivete reigns supreme during adolescence, as do innocent crushes, and using this as a deception tactic merely highlights Ursula’s nefarious mind — augmenting her villain status. To Ursula, Prince Eric is no more than a pawn to be played in her game.

Some will argue that the demographic at play is not mature enough to understand this and will, nonetheless, internalize the misogyny. Yet, while children may not piece together all the complexity, kids are pretty good at drawing one conclusion: “Villains are bad. Don’t listen to them.” Not to mention, much of this film’s viewing audience will be individuals who were kids when the animated version premiered. They’re now well into their 30s (at least). So, could something else be at play?

Ursula has become a source of inspiration over the years, and that changes the game (at least a little bit)

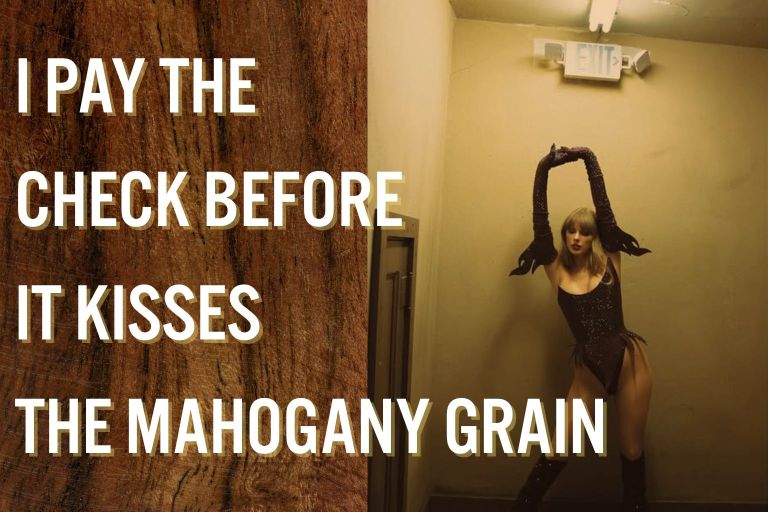

Disney undoubtedly knows that Ursula — who in 1989 was no more than a villain — has become a beloved character (to some, even a hero). Ursula is one of Disney’s only full-bodied villains who claims her space and sashays across her lair with pride. She’s smart and sexy.

She doesn’t quiet herself so as to not draw attention, nor does she aim to take up less space while allowing the patriarchy to spread its legs far and wide. (Her actions directly contradict the misogynistic messaging she employs in “Poor Unfortunate Souls,” further highlighting the verse as exploitative not explanatory). She may be the narrative’s villain, but to so many, she is the indomitable queen to Ariel’s snappable princess.

The generations that first witnessed the Drag Queen-inspired showstopper sing “Poor Unfortunate Souls” has gone on to celebrate the character. There’s even a popular slam poem about the Sea Witch that further humanizes Ursula and underscores just how much she means to fans:

In short, is it possible that the generation that loves Ursula will now be taking their kids to this film — the children they have shared their adoration for Ursula with? With parents on board (at least to some extent) with the film’s antagonist, the possibility of kids internalizing the Sea Witch’s misogynistic messaging increases. Even if just a little.

It may be a bit of a stretch, but Ursula has undoubtedly taken on a positive cultural presence that she did not possess upon her origin. If she’s going to be a villain narratively, yet an inspiration to young girls culturally, maybe it’s wise to ditch the line and avoid the complex dichotomy of the situation altogether.

That being said, the new version deletes one of the most entertaining verses in the song, and it’s a loss on a musical and lyrical front. Ursula shaking her hips as she uses a guttural voice to sing the words “body language” will be a real loss.