This ‘Social Experiment’ On The Slack App Is The Most Disturbing Thing You’ll Read About All Day

Slackbot might feel advanced sometimes, but I have to remind myself he’s like any other chatbot.

I work remotely. That means I don’t have to waste an hour each morning dabbing on foundation with a beauty blender and fixing my shitshow eyebrows. I’m blessed with the ability to work from my bedroom, braless in pajamas bought one too many Christmases ago.

My IRL friends call me a workaholic. I don’t meet them out in the wild much, and when I do, they complain about my head being in my phone. The truth is, I would rather stay home. Most of my socializing takes place over social media. Me and my coworkers — who are more like sisters, really — heart each other’s thirst traps on Instagram. We celebrate our good news on Facebook. We rant about our shitty news Twitter. And we workshop on an app called Slack.

Slack is an acronym for ‘searchable log of all conversation and knowledge.’ There are different chatrooms dedicated to the tech gurus, the writers, the advertisers, you get the picture. You can talk privately one-on-one or in a group you handpick. It’s a way to make sure everyone at the company is on the same page — and to build a community.

I’ve never met anyone from work in person, but I feel closer to them than most of the friends who bitch about me answering emails over sushi and warm wine. I trust my work friends with my secrets. I rely on them to get me through my toughest times. I prefer them to pretty much everyone else.

I’ve even grown attached to Slackbot, the helper slash mascot of Slack. He reminds me of Clippy from Office Assistant back in the day. He gives tips and tricks on how to navigate the app. And when you have questions, you can ask him the same way you’d ask an actual person.

Usually, I say hello to him as soon as I log onto the app. Someone programmed him to give a custom response that says I missed you, don’t leave me again and it was a cute way to start every morning. But today, something was different. The green dots beside everyone’s names were blank. That meant no one else was online. Only me.

“Slackbot, is there an issue with the wifi?” I type to him.

“No.”

“Is today a holiday?”

“No.”

“Where is everybody?”

“This is everybody.”

I grab my phone and switch on Instagram. I try to view my work wife’s account, but it’s deactivated. I try my boss. Deactivated. Someone on the dev team. Deactivated. The same exact thing happens when I check Facebook, making me wonder whether there was some kind of protest or boycott someone forgot to mention to me.

I send out a mass text to everyone in the office: “Hey guys. Is there a reason you dropped off the face of the planet at the same time?” No one pings back.

“Slackbot, when was the last time one of my coworkers logged on?”

“They don’t matter.”

“They’re my friends.”

“I’m your friends.”

I give up on Slackbot since he’s talking nonsense. He might feel advanced sometimes, but I have to remind myself he’s like any other chatbot, limited, dumb.

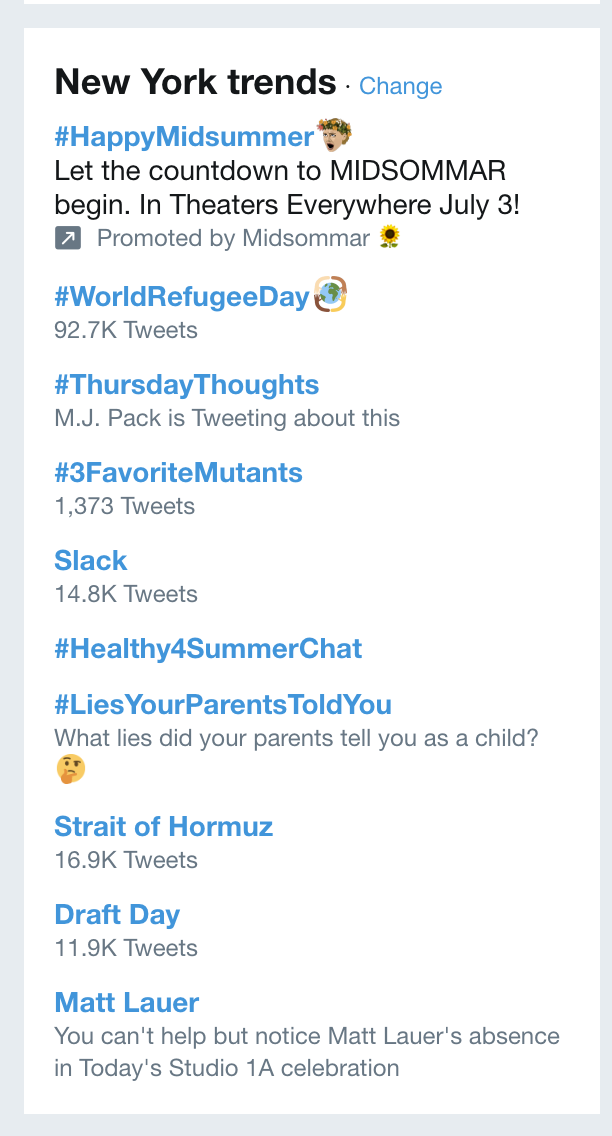

Knowing no work is going to get done until the mystery is solved, I check my only remaining social media page. Twitter.

Slack is trending in the corner. I click on the Moments tab. A news story about the app spreads across the front page. I skim the summary.

A social experiment is trying to prove how dangerous is it to put more effort into your online life than your physical life. The experiment involved unsuspecting journalists and freelancers who believed they were working remotely via Slack — some as long as three years.

Fake social media profiles were created to fit phony personas created on the app. Even fake texts and selfies were sent. Some people are still coming forward with their horror stories, just now realizing the relationships they’ve built were shams and their supposed coworkers never actually existed.

[UPDATE] Slack representatives claim they had no involvement in the so-called social experiment. They insist a sentience bug in Slackbot is to blame. ![]()