Was Queen Katherine Howard Truly Guilty Of Treason, Or Merely The Victim Of A Conspiracy?

Of Henry VIII’s famous six wives, there is no doubt who possesses the worst reputation: fifth wife Katherine Howard. Anne Boleyn may be seen as the “Temptress” but is known as innocent of the adultery and incest charges trumped up to separate Henry from Anne and Anne’s head from the rest of her.

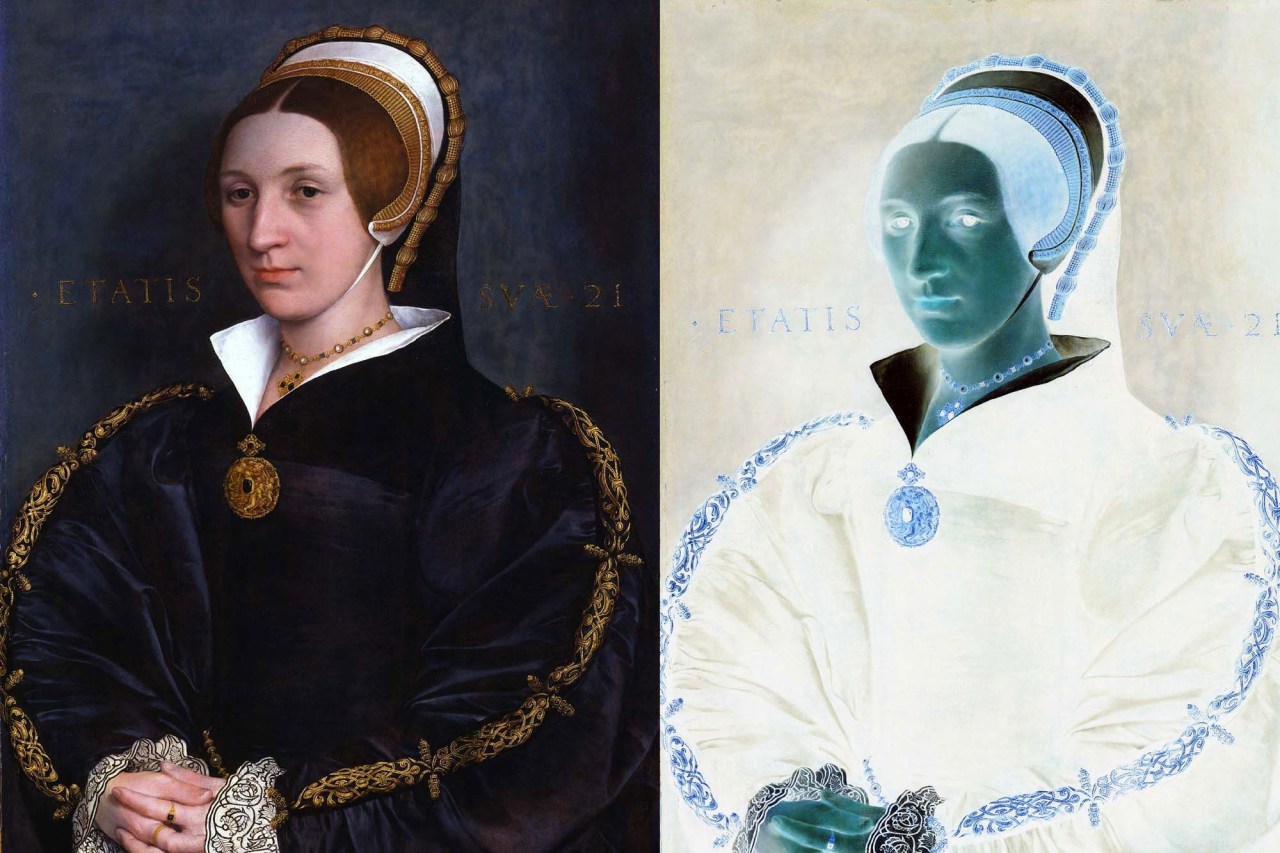

By ![]() Denise Noe

Denise Noe

Ominous Allegations

Only days later, Cranmer left a note with allegations of Katherine’s pre-marital sexual hi-jinks in Henry’s private pew. Henry turned pale as he read that Katherine had enjoyed two lovers in her youth. While not treasonous, it would be enough for Henry to want out of the marriage. Cranmer’s letter stated that courtier John Lascelles had learned of Katherine’s youthful indiscretions from his sister Mary Hall, who had lived at Norfolk House with Katherine under the guidance of Katherine’s step-grandmother Dowager Duchess of Norfolk Agnes Tilney.

Henry put Cranmer in charge of an investigation. Cranmer soon informed Henry that not only had Katherine enjoyed pre-marital sex but she had committed adultery. Norah Lofts writes in Queens of England, only days after thanking God for Katherine, Henry “was accepting – in a passion of tears – some far from conclusive evidence of her infidelity.” Lofts continues that Henry “wept when told what gossip was saying; yet, although they were still under the same roof, he made no attempt to face his wife with the rumors or to hear what she had to say; he simply hurried away from Hampton Court, leaving everything to Archbiship Cranmer who [was] prejudiced against Catherine on account of her religion.”

Indeed, Henry should have suspected a reformist plot. John Lascelles, who had supposedly first informed Cranmer of Katherine’s misdeed, was so strongly reformist that he would be burned to death during Mary Tudor’s reign – as would Cranmer.

“No More The Time To Dance”

Katherine was practicing dance steps in her Hampton Court Palace chambers when a door burst open. Guards told her, “It is no more the time to dance” arrested her, and ordered her to stay in the chambers. She asked to see Henry but was denied.

Katherine’s alleged “paramours” were Henry Manox and Francis Dereham before marriage; Thomas Culpeper after it.

In 1536, Henry Manox tutored Katherine in music. In 1538, Francis Dereham, employed by Katherine’s uncle, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, to conduct business, frequently visited Tilney’s residence. In August 1541, Queen Katherine appointed Dereham usher to her chamber.

Thomas Culpeper, a Gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber and distant cousin to Katherine, was charged as her adulterous partner. There are reports Culpeper once raped a park-keeper’s wife, murdered a villager who attempted a rescue, and was pardoned by Henry for these crimes. However, in Wicked Women of Tudor England, Retha M. Warnicke notes that this story is suspect, being was based on “an unverifiable rumor” that a Tudor contemporary named Richard Hilles reported in a letter months after Culpeper’s execution.

A series of interrogations were made of Katherine, the other suspects, and various “witnesses.”

More than one problem exists with the “confessions” and “evidence” assembled. The “confessions” could be unreliable because possibly extracted under torture; they and the “evidence” could have been manufactured.

However, even as given, much is susceptible to less sinister interpretations – at least regarding Katherine – than usually placed on them. For example, Cranmer reported Katherine confessing: “At the flattering and fair persuasions of Manox, being but a young girl, I suffered him…to handle and touch the secret parts of my body.” This would have been in 1536 – when Katherine was 11 or 12. It would not make her a “delinquent,” but a molested child. Manox is recorded as telling interrogators that he stoked Katherine’s genitals, admitting she was reluctant but claiming she was “content” to permit it. If this did happen, it is more likely she was unable to effectively resist as the era was one in which molested children were often blamed and shamed.

Interrogators claimed Dereham admitted sexual intercourse with Katherine before her marriage but said he and Katherine were “pre-contracted” in marriage. In those days, saying you were married and consummating it through intercourse made you married. Katherine is recorded as saying, “Francis Dereham by many persuasions procured me to his vicious purpose and obtained first to lie upon my bed with his doublet and hose…and finally he lay with me naked and used me in such sort as a man doth his wife many and sundry times.” She was 12 or 13, either not yet or just barely a teenager. Cranmer reported Katherine insisted Dereham used “force” and “violence” and she never willingly had sex with him. That Katherine appointed Dereham usher does not mean she could not have been raped by him; the knowledge she was not a virgin meant a potential for blackmail, making her beholden to her rapist.

Cranmer also said Katherine adamantly denied a pre-contract. Historians have been baffled by this denial since it could have annulled her marriage to Henry and saved her life. Some have thought she was too stupid or too upset to realize the escape offered; Denny ascribes her denial to “pride.”

Lofts suggests Katherine showed “integrity” in her “refusal to take the easy way out which a previous marital arrangement with Dereham offered.” Warnicke observes, “The church required a [marriage] vow be freely given and not coerced.” Katherine may not have considered herself pre-contracted if Dereham raped her. Warnicke elaborates, “[Katherine’s] denial was consistent with the claim that Dereham forced his attentions upon her.”

Indeed, Katherine sounds principled when asserting, “I am innocent of all charges and will never admit to these lies. If there is any ground of truth in these statements, then it is because of childish ignorance and the evil companions with whom I was formerly surrounded. I also seek to state that I am faithful to the King and would never wish harm upon him. I will seek his mercy but not by admitting to these treacherous lies.”

Cranmer reported Katherine admitted meeting with Culpeper but insisted Culpeper touched no part of her body other than her hand and that Katherine’s Chief of Privy Chamber, Jane Parker, Lady Rochford, had always been present. Katherine also said she had told Jane, “I pray you, bid him desire no more to trouble me or send to me.”

Jane contributed to the tragedy suffered by Katherine’s cousin, Anne Boleyn. From a strongly Catholic family, Jane probably resented Anne Boleyn’s role in England’s break with Rome. The Parkers supported Katherine of Aragon and Princess Mary after Anne became Queen. Anne sent Jane from court in 1534. In the trial of Anne, Jane testified that her husband, Anne’s brother George Boleyn, had committed incest with his sister, helping ensure their executions.

Although Dereham denied relations with Katherine after she was Queen, interrogators extracted a “recollection” from his friend Robert Davenport that Dereham once remarked, “If the King were dead I am sure I might marry [Katherine].” A recently passed law made it treason to “maliciously wish, will or desire by words or writing” harm or death to the King so that was enough to execute Dereham. Lofts observes that the “recollection” is suspect since interrogators knocked out Davenport’s teeth to get it!

Katherine was taken to Syon Abbey and incarcerated in a sparsely furnished room. On November 24, a formal indictment was issued against Katherine for leading “an abominable, base, carnal, voluptuous, and vicious life.”

While Culpeper denied sex, he supposedly admitted intending “to do ill with her,” also sufficient for execution.

Culpeper’s room at court was searched. Investigators said they found a letter from Katherine in that room. The letter was taken as proof of treasonous adultery.

Katherine has been damned as an adulteress in many eyes by it.

Master Culpepper, I heartily recommend me unto you, praying you to send me word how that you do. It was showed me that you was sick, the which thing troubled me very much till such time that I hear from you praying you to send me word how that you do, for I never longed so much for [a] thing as I do to see you and to speak with you, the which I trust shall be shortly now. The which doth comfortly me very much when I think of it, and when I think again that you shall depart from me again it makes my heart to die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company.

It my trust is always in you that you will be as you have promised me, and in that hope I trust upon still, praying you that you will come when my Lady Rochford is here for then I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment, thanking you for that you have promised me to be good unto that poor fellow my man which is one of the griefs that I do feel to depart from him for then I do know no one that I dare trust to send to you, and therefore I pray you take him to with you that I may sometime hear from you one thing.

I pray you to give me a horse for my man for I have much ado to get one and therefore I pray send me one by him in so doing I am as I said afor, and thus I take my leave of your, trusting to see you shortly again and I would you were with me now that you might see what pain I take in writing to you.

Yours as long as life endures,

Katheryn

One thing I had forgotten and that is to instruct my man to tarry here with me still for he says whatsomever you bid him he will do it.

A love letter? Maybe not. Warnicke notes that the beginning, “Master Culpeper,” is “quite abrupt” since “Cupeper was a knight and a member of the privy chamber and thus deserved a title.” Lady Lisle wrote a 1537 letter to him beginning “Good Master Culpeper.” Warnicke writes that Katherine’s sympathy with him about a recent illness may have been an attempt to “placate him with politeness.” Warnicke reports that phrases such as “at your commandment” were part of the “elaborate contemporary formula of letter-writing.” Culpeper had used that exact phrase in a letter to Lady Lisle – and no one has suggested they enjoyed a romance.

The sign off may not indicate intimacy. Warnicke observes that “Yours” was a standard sign off. In letters to Cromwell, Mary Tudor signed off “Your loving, assured friend during my life” and Elizabeth, Duchess of Norfolk, signed off “By yours most bounden during my life.” Neither woman was suspected of intimacy with Cromwell. Warnicke believes the word “endures” indicates tension.

Warnicke writes, “The two items on the fearful queen’s agenda were that she desperately wanted to speak with Culpeper and learn whether he would keep his promise to her.” Warnicke believes Culpeper was blackmailing Katherine with knowledge of her having not been a virgin at her marriage and that he may have been sexually harassing Katherine.

A Plot To Take Down A Queen

Ten years of research led writer Elisabeth Wheeler to conclude that Katherine was the victim of a plot in which “reformists Cranmer, [Thomas] Audley, and [Charles] Suffolk” sought to bring her down. Wheeler found it “necessary to dismiss the gathered evidence against Catherine and look instead at the interrogators themselves.” Wheeler believes that having a devoutly conformist queen was “an unthinkable blow to the reformists.” In addition, there was much resentment against the Howard family which many saw as overly ambitious and proud. Commitment to religious reform and dislike of the Howards led powerful men around Henry to plot against Katherine. Wheeler believes reformists need “to get rid of [Katherine] before a male heir would be born.”

Wheeler also believes Henry himself was a victim of “a diabolical plot by his inner cabinet to deprive him of his queen and the chance to provide sufficient male heirs for the security of the realm.”

It is also possible that, as Wheeler believes, Katherine’s interrogators created “a faked and forced confession.”

Wheeler also suggests that the supposed “love letter” from Katherine to Culpeper, may have been forged. In Wheeler’s judgment, the “first eight words” of that epistle are “written in a different hand, in a small neat script” distinct from the rest.

Men of Power makes a strong case that reformists sought to destroy a possible threat and that neither “confessions” nor “evidence” should be taken seriously.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-mUMWUcQvo&w=560&h=315%5D

Belated Fairness For The Fifth Queen

Unlike Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard was allowed no public trial. Perhaps the reason for this is that Anne answered the charges so astutely. Thus, Katherine was not allowed the same chance.

It may be that Katherine Howard was the victim of child molestation and rape when young; of sexual harassment and blackmail when queen. It may also be that her supposed partners were also innocent and, like her, victims of a plot to take down a possible threat to the Privy Council reformists. In either case, she was unfairly judged and that unfairness continues to this day.

The general perception of Queen Katherine Howard renders her death a matter given little weight. Someone as giddy, reckless, and utterly irresponsible as she is often considered would be unlikely to accomplish much even had she lived a normal lifespan. Hopefully, this story will lead at least some readers to a more positive view of her character, to see her as compassionate, and to consider the possibility that she was falsely accused. If some readers see her execution as a genuine tragedy, this story has accomplished its purpose. ![]()