Was Queen Katherine Howard Truly Guilty Of Treason, Or Merely The Victim Of A Conspiracy?

Of Henry VIII’s famous six wives, there is no doubt who possesses the worst reputation: fifth wife Katherine Howard. Anne Boleyn may be seen as the “Temptress” but is known as innocent of the adultery and incest charges trumped up to separate Henry from Anne and Anne’s head from the rest of her.

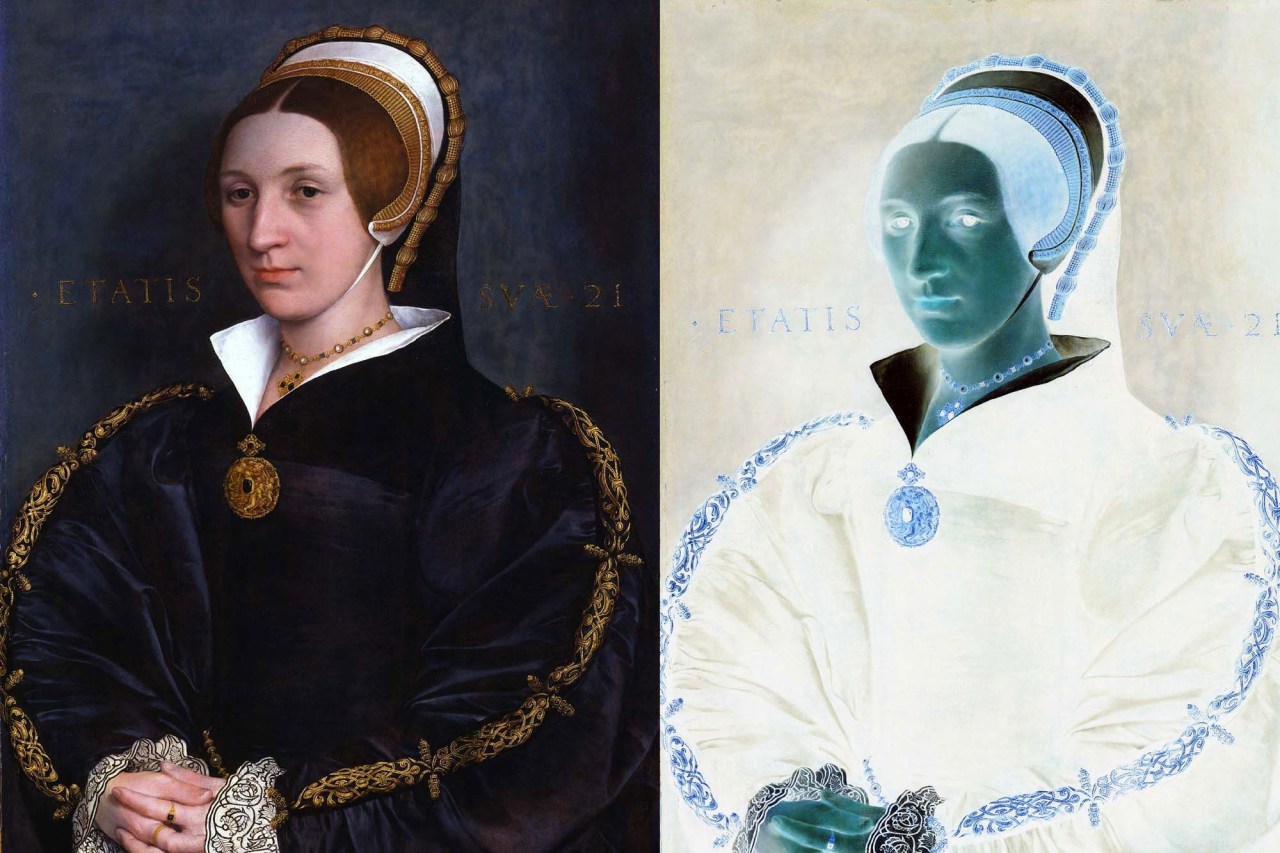

By ![]() Denise Noe

Denise Noe

Of Henry VIII’s famous six wives, there is no doubt who possesses the worst reputation: fifth wife Katherine Howard. Anne Boleyn may be seen as the “Temptress” but is known as innocent of the adultery and incest charges trumped up to separate Henry from Anne and Anne’s head from the rest of her.

As author Antonia Fraser observes, Katherine Howard is viewed as the “Bad Girl,” a 16th Century Miss Hot Pants recklessly enjoying premarital dalliances and even more recklessly committing adultery when a queen’s adultery was treason.

Modern people may sympathize with a woman who lived in a culture in which losing her head over a man could mean – well, losing her head. However, that sympathy is tempered by viewing Katherine as a shallow, horny, hedonist.

Historian Karen Lindsey accepts Katherine’s guilt but attempts a positive spin, seeing “courage to [Katherine’s] reckless affair with Culpeper” because she was “a woman who listened to her body’s yearnings.” Trying to force a 16th Century Queen into a contemporary feminist, Sex Revolution mold does not quite gel.

Some writers, including this one, question Katherine’s guilt.

A New Church And The Battle For Its Soul

To understand Katherine’s tragedy, we must review the link between Henry’s marital history and religious conflict. When the Pope refused to annul Henry’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Henry founded the Church of England of which he was head so he could annul that marriage, enabling him to wed Anne Boleyn. Except for being headed by Henry instead of the Pope, the new church was as Catholic as the Roman Church.

However, many hoped to “Protestanize” the new church. Anne Boleyn herself was among the “reformists.” Holy Roman Empire Ambassador Eustace Chapuys derided her as “more Lutheran than Luther himself.”

“Conformists” wanted to preserve Catholic ways and hoped to reconcile with Rome.

Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn typifies the old saying, “Be careful what you wish for, you might get it.” After pursuing Anne for years and founding a new church to get her, Henry soon tired of her. Her births echoed those of her predecessor: daughter Elizabeth followed by multiple miscarriages.

Thus, Anne Boleyn’s execution on May 19, 1536.

Only a child at the time, Katherine Howard must have been proud when her cousin became queen but dismayed by her disgraceful death. However, the rift between England and Rome that Anne triggered also triggered a rift between the Boleyn and Howard wings of the family. The latter were solidly conformist. In Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy, Joanna Denny writes, “[Katherine] lit candles for her dead parents, ate fish on Fridays and said her prayers by rote in the happy assurance that whatever she did would be forgiven in the confessional.”

Henry’s marriage to Jane Seymour provided an heir but her death led to the search for a wife to birth a “spare.” Since Henry was a second son, taking the throne after brother Arthur’s death, he knew the importance of an extra.

Reformists tasted triumph when Henry agreed to marry Anne of Cleves who hailed from the Protestant German state of Cleves. They were undoubtedly crushed when Henry found her so repulsive he could not consummate their marriage.

After ridiculing Anne as a “great Flanders mare,” Henry’s eye was caught by one of her ladies-in-waiting: petite, graceful, fair-haired Katherine Howard.

Perhaps her tender age was a strong attraction. Denny argues, “The anonymous Chronicle of Henry VIII reports Katherine was 15 when she first met the King in late 1539, making her year of birth 1524 or 1525.” Denny elaborates that the traditional view that Katherine was born in 1520 or 1521 was based on a French Ambassador’s “guesswork.” Contemporary observers frequently mentioned her “youth” which supports the earlier date as they would be unlikely to comment on it had she been older than that date suggests.

Conformists hoped Katherine would influence Henry to hold the line against Protestant tendencies and perhaps even bring him back under the Pope.

Henry married Katherine on July 28, 1540.

A Caring Queen

Graciousness and compassion characterized Katherine’s Queenship. Anne of Cleves visited the newlyweds and knelt before Katherine who lifted her up. When Anne rose, Henry hugged and kissed his “sister” before they dined. Katherine and Anne danced together. Katherine gifted Anne with two small dogs and a ring.

Katherine took a protective interest in cousin Anne Boleyn’s daughter, seven-year-old Elizabeth, playing with the child and giving her trinkets.

Although Katherine and Mary Tudor shared religious persuasions, there were reports of early tension between them. It had apparently dissipated by May 1541 when Katherine approved Henry’s granting permission for Mary to live at court.

In Men of Power: Court Intrigue in the Life of Catherine Howard, Elisabeth Wheeler writes that Katherine “sent warm clothing” to elderly Lady Salisbury Margaret Pole, imprisoned for treason for Papist sympathies. However, Katherine could not persuade Henry to pardon Salisbury who was later executed.

Denny writes, “In February [1541] [Katherine] intervened in the case of Sir Edmund Knyvet, who was involved in a quarrel with Thomas Clere.” Clere was injured and Knyvet sentenced to have a hand amputated. Henry approved the sentence. Katherine begged him to withdraw that approval. He did – just in time. A terrified Sir Edmund learned of the clemency just before his hand was to be severed.

Sir Thomas Wyatt was another beneficiary of Katherine’s kindness. An informer reported Wyatt had made treasonable statements. Thrown into the Tower, a baffled Wyatt said he had no idea “whereby a malicious enemy might take advantage by evil interpretation.” Even though he was a reformist, the conformist Queen rescued him. Chapuys wrote that Henry and Katherine “passed through London by the Thames the people gave her a splendid reception, and the Tower guns saluted her. From this triumphal march she took occasion to ask the release of Wyatt.” Henry pardoned Wyatt. Katherine also successfully persuaded Henry to pardon suspected traitor Sir John Gallop and suspected felon Helen Page.

On November 1, 1541 All Saints Day, Henry ordered churches to offer special prayers of thanksgiving for Katherine, his “jewel of womanhood” and “the good life he led and trusted to lead” with her.