Don’t Click On This Link — Don’t Visit This Website

If the government doesn’t know about it, they should. After what happened to me. After what could happen to someone else.

When I was little, the only books I read were mysteries. Nancy Drew. Wishbone. The Adventures Of Mary-Kate and Ashley. I even had monthly detective kits delivered to the house, filled with fingerprint dust and invisible ink.

When I got older, I gave up my deerstalker in pursuit of a graduation cap and a degree in psychology, but mysteries remained a hobby of mine. Whenever I had a minute to breathe, I read Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie. Or I played a game.

The Game.

I heard about it on Reddit, in one of the controversial sub-categories that some users have filed complaints about. One that revolves around NSFW pictures of corpses and stories from morticians, masochists, and necrophiliacs.

In bright blue letters, the title said, “Don’t click on this link.”

So, obviously, I clicked.

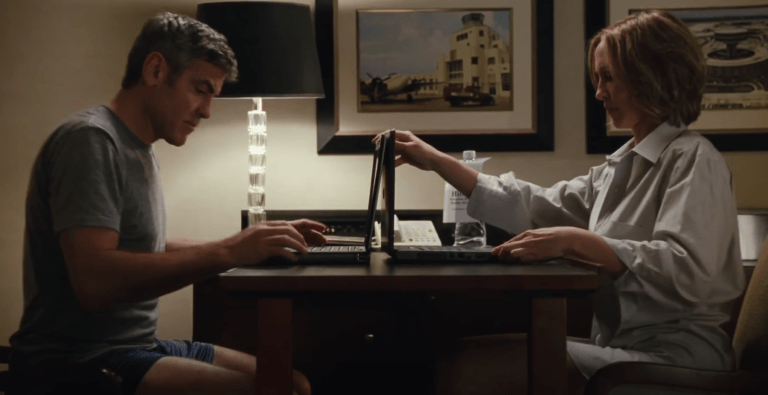

I was directed to a website where I got to live out my childhood dreams. All I had to do was choose a date and a location (a calendar popped up with arrows next to the month and year, along with a map of the US) and I would see photographs of a real crime scene. Blood smears on the floor. Broken glass pooled beneath the windows. Yellow tape sectioning off the area.

It was more than a game. It was an exercise. A riddle. I had to look at all the photographs and try to figure out what happened. Did someone get hurt? Did someone die? If so, who was the victim? Who was the murderer? And most importantly, why did they do it? What was their motive?

If I went decades back on the calendar, the pictures that popped onto my screen would be dark and grainy. Hard to see. Even harder to piece together clues.

But if I clicked on a more recent date, say Wednesday of last week, I’d see more than 4×6 pictures. I’d get a 360° panoramic version of the crime scene. I could click on the kitchen and poof — I was in the kitchen. I could click on an up arrow and see burn marks on the ceiling, click on a down arrow and see blood on the tiles. It was like I had stepped inside of a different world, and all I had to do was turn my neck to examine the different areas of the house.

It was fun as long as I thought of it as fiction, but once the reality set in, it felt intrusive. Immoral. Illegal?

Some users swore that the government already knew about the site. Some even had a theory that they set it up themselves, because internet nerds were detailed, perceptive. They could solve the case for the police while they sat on their asses. Get paid to do nothing.

Me? I never had a concrete opinion on it. But if the government doesn’t know about it, they should. After what happened to me. After what could happen to someone else.

It was all because of a miss-click. After choosing Alabama on the map, my home state, I accidentally clicked on today’s date instead of a date from the past. I assumed I’d be met with an error message.

Instead, I saw my living room. The same flat screen television, propped on a table instead of mounted on the wall. The same three-bulb lamp, arms extended like a willow tree. The same brown couch, stained with cigarette butts and dark marks from the dog’s tongue.

How did the game do that? At first, I thought that was the mystery. Try to figure out how the programmers got inside of your house, inside of your head.

Maybe my computer camera had been turned on at some point over the last three months of my obsessive game playing. The laptop scanned the room. Took photos. Turned them into a panoramic masterpiece. It was the twenty-first century. We were always being monitored, watched by little lights in our electronics. It wasn’t impossible.

In fact, it was kind of cool, once you got past the whole you’re-never-really-alone-because-big-brother-is-everywhere idea.

That’s why I clicked on the dining room (my dining room) and jumped there to investigate. My bay window had three holes through it, bigger than bullets, but smaller than fists. When I looked at the window seat, which I used more as a shelf, the little figurines that usually lined it were toppled over. Some missing. Maybe they were what had been thrown out the window? They were about the right size.

I pressed the down arrow to explore more and saw blood. Blood on the wooden floors. Blood on the area rug. Blood trickling out from a body with a knife jammed through the neck.

Cute. The program probably scanned my face while I was playing. It didn’t take a genius to figure that out. I knew what to expect. When I pressed the down arrow again, when I looked close at the body slumped on the ground, it would have my features. It would be meant to scare the hell out of me. Like a jump scare in the middle of a Youtube video that you’re not supposed to see coming, but can always sense.

But when I zoomed in, I realized I was wrong. It wasn’t me. The eyes were a slightly different shade of blue. The arms were spotted with brown. The eyebrows were thinner, the lips thicker.

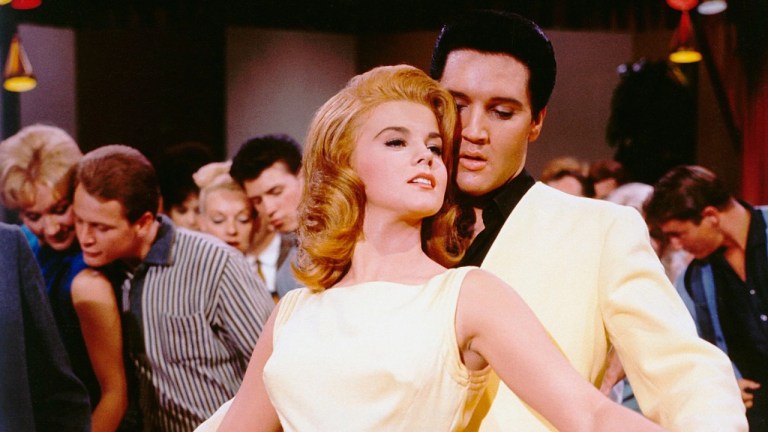

It was me, except older. It was my mother.

But she’d never been in my apartment, never been near my laptop and the pinhole eye of the camera. We had a… strained relationship. One that grew worse with age.

She was supposed to visit that weekend, but I had canceled on her at the last minute. Got annoyed by all of her Scientology talk. Threw a tantrum like a little girl, texting her that I hated her and her cult. Texting, because I didn’t want to hear her voice. To feel bad and apologize.

I tried to disconnect, to treat the game like I always did and search for clues to solve the mystery. The first thing I noticed were the bloody tracks across the floor, from a size eight or nine shoe, the same size I wore.

Then there were the shattered figurines — Precious Moments figurines. They were gifts that my mother had given me on my birthday, every year since I was born.

And there was my cell phone on the counter. The phone with the nasty texts. The texts that made it look like I hated my mother.

Like, maybe, I had reason to kill my mother.

If I was playing the game as an outsider, I would’ve sworn I had done it. If I was a cop, I would have thrown handcuffs around my wrists.

Thwump. Thwump. Thwump.

It took me a minute to realize the knocking wasn’t coming from my headphones, but from my front door. My mother must have been outside, suitcase rolling behind her. Of course. She already had a plane ticket. Had requested off from work. Of course she was here. What did a little argument matter?

I should’ve turned off the game to greet her, but I was afraid to answer the door. Afraid of myself.

Would I take her life, because the game implanted my mind with the idea? Or because the game could see into the future, could predict what I was destined to do? No. No, there wasn’t any scenario where I was a killer. I love my mother. She annoyed me, frustrated me, angered me, but I loved her.

I must’ve sat there, a statue in front of my computer, for a little too long, because she was in the house now. Calling my name. Asking if I was home. She must have found the key hidden beneath the garden stone on my stoop.

I wished she would go away. I didn’t want her anywhere near me, and not for the same reason I had a few hours ago. I wasn’t mad at her anymore. I didn’t dread listening to her rants about abortion and alcohol and atheism. I wanted to protect her. I wanted to keep her safe. I wanted to protect her from myself.

But I wasn’t a killer. I wasn’t a killer. I wasn’t a killer.

I was still repeating those words when I heard the glass shatter (once, twice, three times). When I heard the scream. When I bolted into the dining room and saw a gloved man escaping, a knife deep in my mother’s neck, and my own sneakers leaving trails through the blood.

I was right. I wasn’t a killer.

I was being framed. ![]()