America’s Only Unsolved Skyjacking Still Haunts The FBI Over 50 Years Later

By Erin Whitten

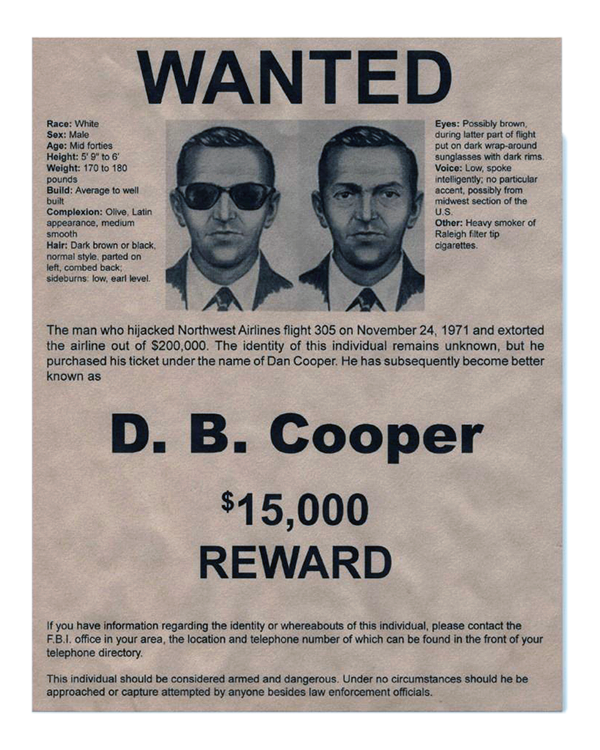

It was the evening before Thanksgiving in 1971 when a man who called himself Dan Cooper walked up to the ticket counter at Portland International Airport and paid cash for a round-trip ticket to Seattle. He looked like a businessman to the ticket agents and the other passengers. He was in his 40s, black hair parted in the middle, brown eyes, wearing a suit and raincoat and clip-on tie, clutching a briefcase and a paper bag. Inconspicuously, Cooper took a seat in the back of the Boeing 727 and ordered a bourbon and 7-Up. That is exactly when everything changed – and where Cooper showed he wasn’t here for just any other business trip.

After the plane took off a few minutes later, he gave a note to flight attendant Florence Schaffner. She assumed it was a telephone number. He told her, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.” The note, just like the flight, was brief and clear. He wanted $200,000 in cash and four parachutes, to be waiting for him when the plane landed. To reinforce his message, Cooper opened his briefcase to reveal a neat row of red cylinders, wired to a battery. Captain William Scott was notified, and for the next two hours the jet circled Puget Sound while police and FBI agents frantically tried to assemble the ransom. Passengers were told only that the flight had a minor mechanical problem and would be delayed.

Flight 305 touched down in Seattle at 5:46 p.m. The exchange took place in near darkness at the edge of the runway and all of the passengers walked free while a ground crew placed $200,000 in $20 bills and the four parachutes on a table. Cooper had kept his promise to let the passengers go, but he ordered the crew to stay on board. Flight attendant Tina Mucklow became his messenger, carrying the parachutes and the bag of cash to the rear of the plane. With the money safely in his possession, Cooper made his next demands. The plane was to fly south toward Mexico City, as slowly and as low as possible, with a stop to refuel in Reno. He even dictated flap settings and insisted the cabin remain unpressurized which suggested he had a pilot’s familiarity with the 727’s systems.

About half an hour after leaving Seattle, the cockpit instruments registered the rear staircase lowering. At 8: 13 p.m., the jet gave a sudden upward jolt, as if a great weight had suddenly been dropped. By the time the plane rolled into Reno just before midnight, it was surrounded by FBI agents. They swarmed through the cabin, but the hijacker, the cash and two of the parachutes, had vanished.

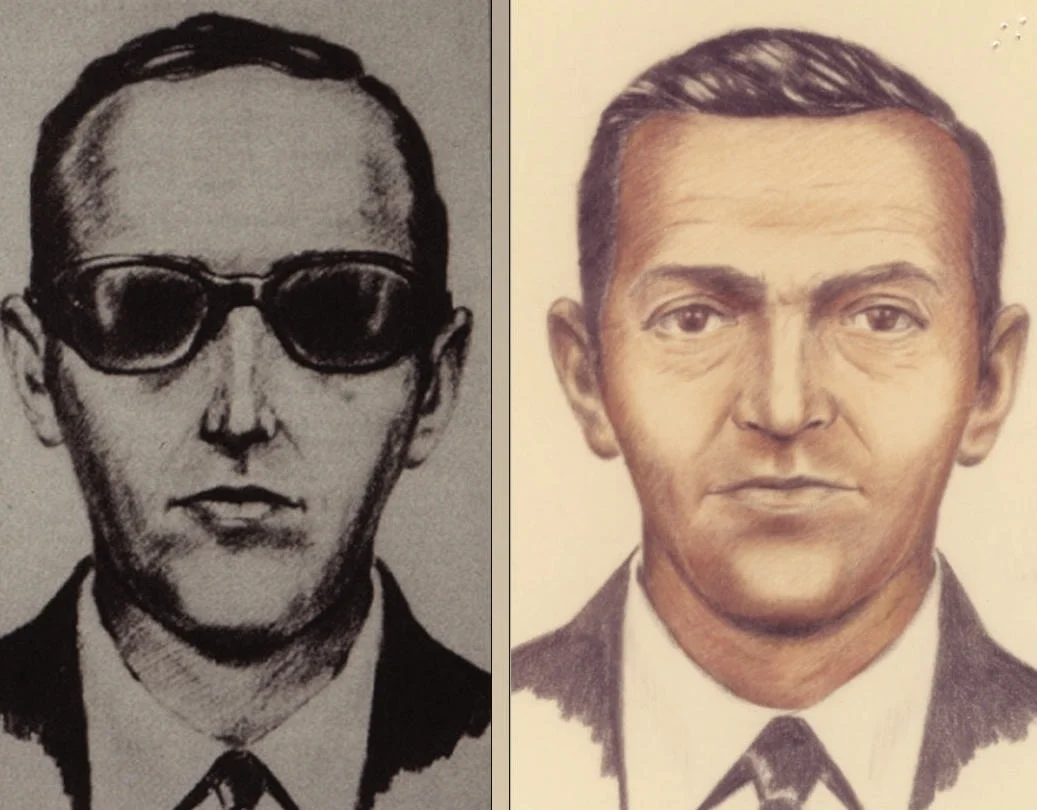

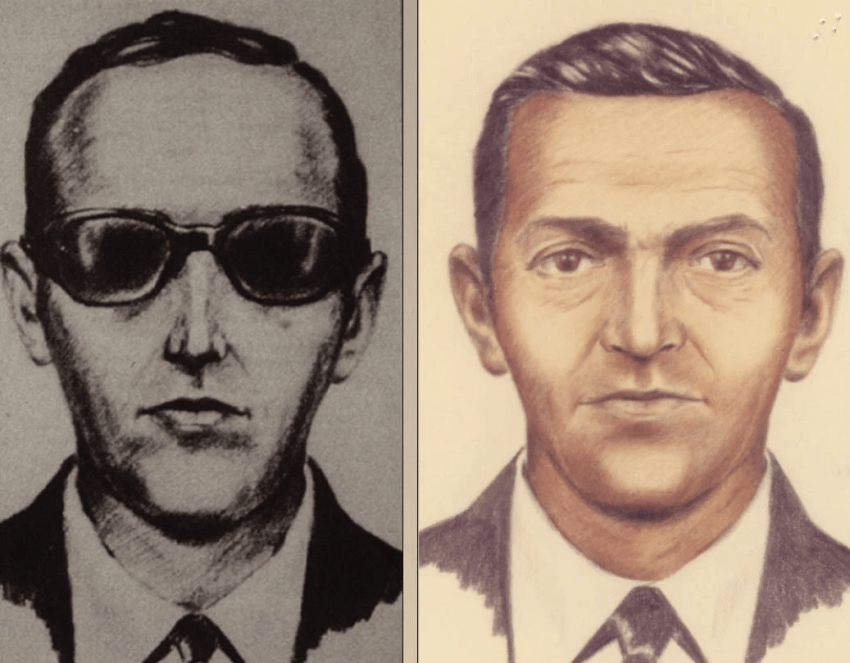

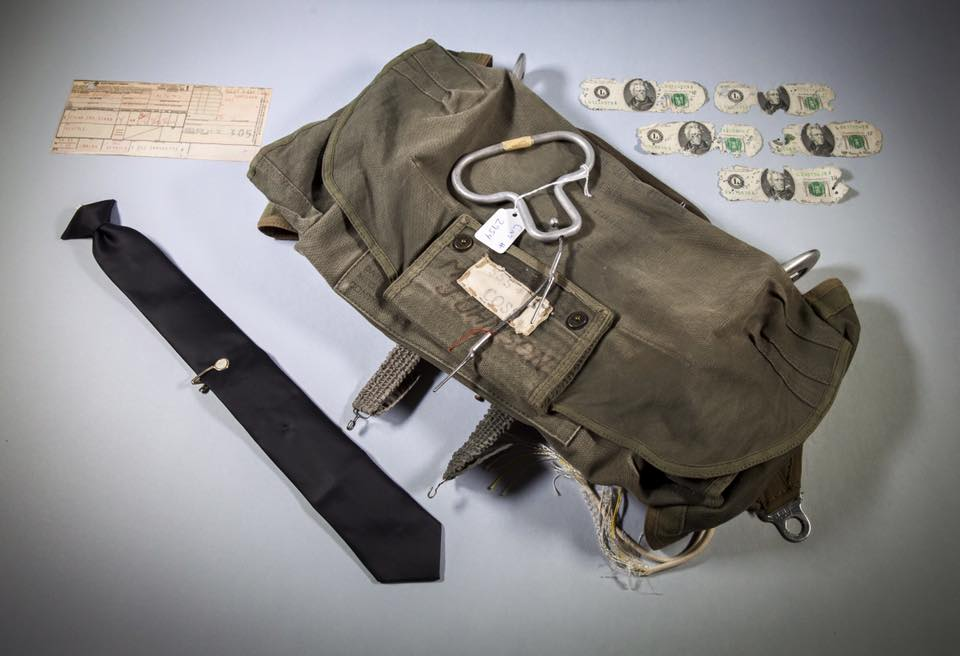

Agents from the FBI searched the cabin and gathered up his few personal items left behind, including a black clip-on necktie, a mother-of-pearl tie clasp, and some cigarette butts in the armrest ashtray. Dozens of latent fingerprints were dusted off the plane, but none could be definitively matched to a suspect. Every eyewitness was interviewed, and within days composite sketches of the mystery hijacker were distributed nationwide.

Identifying a more specific area to search, however, proved far more difficult than anyone had anticipated. There was no way to know precisely where Cooper had left the aircraft. The jet’s airspeed and altitude had been approximate, the weather was turbulent, and only Cooper knew how long he’d waited after jumping to deploy his ripcord. Fighter jets tracking the 727 that night reported no activity. Teams of investigators combed the forests, rivers, and farmland of southwest Washington. Helicopters and boats were deployed, and in one particularly creative case a submarine was even pressed into service. The team searching the region scoured thousands of acres over the next few months, but they found no trace of Cooper or his equipment.

The FBI would eventually review more than a thousand potential suspects, ranging from former paratroopers and convicted embezzlers to amateur skydivers and escaped convicts. One of the most scrutinized was Richard McCoy Jr., a skydiver who executed a near-identical hijacking just months later. McCoy was eliminated from consideration by flight attendants who said he didn’t fit the memory of the man they’d known. Other suspects were floated over the years: Sheridan Peterson, a Boeing employee and experienced skydiver; Robert Rackstraw, a self-described con man and small-plane pilot with a colorful history, and Kenneth Christiansen, a former Northwest Airlines employee whose brother later claimed the company defrauded him of his identity, and who his brother later claimed had confessed to the crime on his deathbed. None of these or the hundreds of other leads would prove any more fruitful.

The only real break in the case came in 1980, when an eight-year-old boy digging along the Columbia River discovered three packets of decomposing $20 bills partially buried in the sand. The serial numbers matched Cooper’s ransom payment. The find raised as many questions as it answered. Had Cooper died in the jump, and had the money been scattered downstream in his fall? Or had he hidden it, and only the river later uncovered it years later? No additional bills have been found.

For years, amateur sleuths and seasoned investigators obsessed over every detail of the case. The FBI would even conduct experimental test flights, using weighted sleds to recreate Cooper’s jump in order to better understand the turbulence and conditions he would have faced. In 2016, after 45 years of investigation, the FBI announced they were officially closing the case, saying their resources would be better spent on other, more tangible cases. The files however, yes all 66 volumes, complete with handwritten notes and sketches remain publicly available.

Theories about Cooper’s ultimate fate remain split among investigators to this day. Many are convinced he died in the jump, falling into the dense, mountainous forests with no survival equipment, only to be consumed by the elements. The sheer improbability of his escape and the fact that a substantial amount of his ransom cash has never been found suggests to many that he lived. Copycat hijackers in the years that followed managed to parachute from 727s and survive, and that fact keeps alive the belief among many that Cooper did too, and lived quietly for years under another name. One thing is for certain, no conclusive evidence has ever been recovered, and no suspect has ever been definitively identified. Fifty years later, D.B. Cooper’s dive into the storm over the Pacific Northwest remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in American history.