Everything You Need To Know About Confidence, Ego, And Humility Explained In One 3,000 Year Old Story

If confidence is knowing your strength, humility is an awareness of one’s own weaknesses.

By ![]() Ryan Holiday

Ryan Holiday

The ancient story of David and Goliath helps explain confidence, and the timeless problem of the ego and humility ratio.

We generally admit that humility is a virtue and ego is a vice. Yet this black and white definition is made complicated by the fact that any sensible person would also admit that confidence is important.

We’d say it’s more than important—we know that confidence is essential. After all, if you don’t think you can do something—if you’re crippled by fear for instance—you’re probably not going to be able to do it.

Which is why it is such a tough and eternally vexing question: What’s the difference between self-doubt and humility? Where does confidence end and ego begin? Is it about degrees? How much should you have of each? Or are the traits opposed to each other? And if ego is so bad, why do so many successful people seem to have big ones?

The truth is that like all important things the answer is complicated. There is no magic number of units you’re supposed to have of each, no modern solution to this timeless problem. Which is why, as worn as the story has become, there is no better lesson about the dangers and benefits of confidence and ego and humility than the story of David and Goliath.

If we go back in time then, to 1000 BCE, we’d find Israel and Philistine locked in terrible war in the Valley of Elah. It would be the great Goliath who issued his bold challenge to the Israelites, offering to put an end to the stalemate between his army, the Philistines, and theirs. “This day I defy the armies of Israel! Give me a man and let us fight each other,” he shouted as he paced up and down the lines of soldiers. His offer was simple: if a man could beat him, the war would be over and his people would submit. If he beat them, the Israelites would be forced submit to him.

For forty days, twice a day, Goliath repeated this challenge. Not a single soldier stepped forward, not even the King of Israel, King Saul. In fact, the Israelites trembled in fear. They huddled inside their lines, believing it to be impossible to defeat this giant (who according to the texts was either 6’9’’ or 9’9’’ tall and incredibly strong). These were supposed to be the bravest men in all of Israel, but they were paralyzed, frozen in fear.

This, if you’re wondering, is the definition of cowardice. It’s not like a different soldier tried every day for a month and all were defeated. No one tried. Of course they should have been afraid—but courage is what you do when you are afraid. It is the triumph of training and spirit over fear. It’s not as if the army came up with all sorts of different attacks and were repulsed. They did nothing. They just waited. They just hoped he would go away.

Then comes young David. David is a shepherd and three of his brothers are serving in the army. He comes to visit and while he’s there with them, he hears Goliath’s daily challenge. He asks his brothers about it and they make fun of him—as if their little brother could even comprehend what was happening. David brushes aside their teasing and approaches King Saul about undertaking the challenge. Once again, he is dismissed. This is the power of cowardice, cowardice and ego. The other soldiers, including David’s own brothers, are so certain of their own beliefs that they find it impossible than any other reality than one dominated by the fears they feel.

But David is not convinced by their cowardice, he sees the situation with fresh eyes. He responds to the king’s dismissal by pointing out that for years he has bravely kept watch over his father’s flock.

“When a lion or a bear came and carried off a sheep from the flock, I went after it, struck it and rescued the sheep from its mouth. When it turned on me, I seized it by its hair, struck it and killed it. Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be like one of them, because he has defied the armies of the living God.”

This then is the definition of confidence. David has evidence (not simply belief) that he can successfully face this challenge because he has faced similar challenges in the past with bravery and strength. He has killed lions and bears with his own hands. He knows what he is capable of. He knows courage. Religious people would also say that he has the comfort and security of his belief in God and whether you agree with that or not, it’s undeniable that this was a source of strength and purpose for him. It’s part of his confidence.

So how does Goliath respond to seeing this tiny challenger emerge in front of him? He responded like most egotistical bullies. He laughed. He said to him, “Am I a dog, that you come at me with sticks?” Goliath could see only a small boy, not a threat. “Come here,” he said, “and I’ll give your flesh to the birds and the wild animals!”

This then is ego. Goliath had gone unchallenged for so long, he had begun to see himself as invincible. David might have had strong faith in his god. Goliath, because of his size, his strength, his position, had come in part to believe he was a god. There is an argument that David was crazy. That Goliath was right to dismiss him, that it wasn’t ego but deserved confidence. Except subsequent events would prove that demonstrably false. And indeed it was this ego, this inability to see the threat that a smaller, nimbler, courageous opponent might represent that would be the opening that would make it possible for Goliath to be defeated. We often miss that in discussions about ego—that it sows the seeds of its own destruction—but here it is obvious and undeniable.

I know you think you know the end of the story and I know I’ve just hinted it at it, but there is another variable to look at, and it has to do with how David challenged Goliath. When King Saul allowed David to fight Goliath, he first insisted that he wore the standard armor and helmet of a soldier. David tried them on, but found it impossible to move, being so small. “I cannot go in these,” he replied, “because I am not used to them.” Instead, David went in his shepherd’s clothing and fished a few stones out of the river.

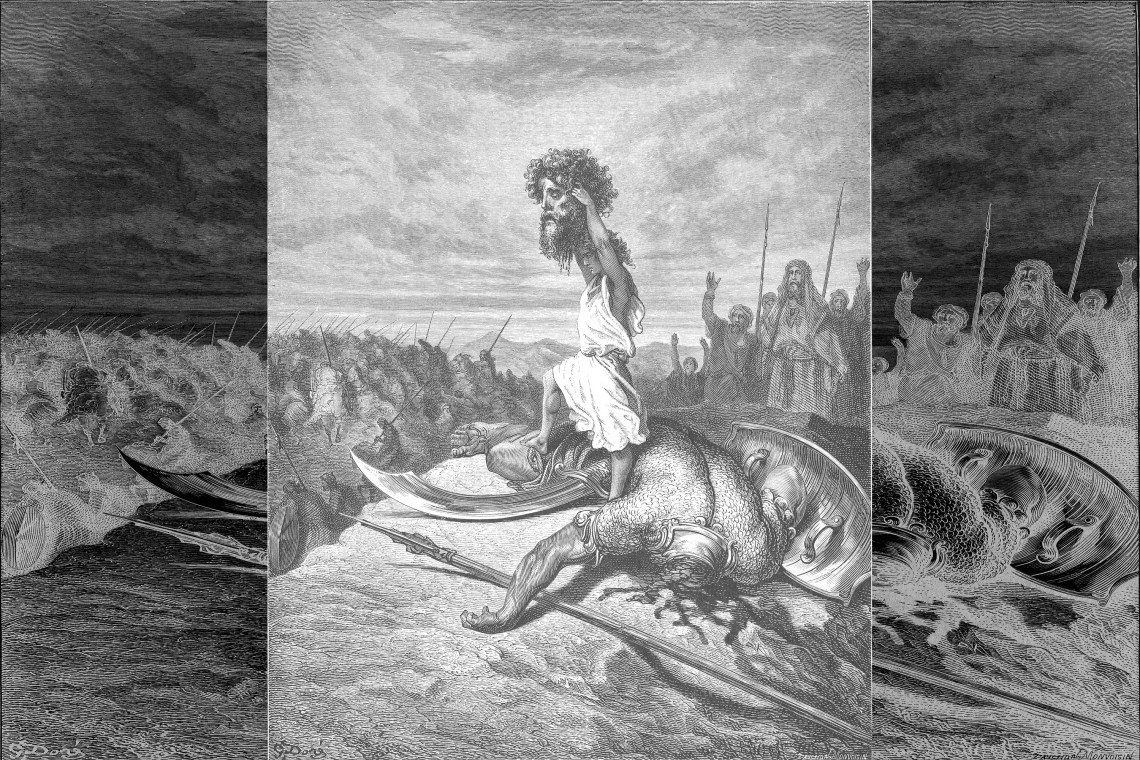

Believing that he couldn’t beat Goliath in an even matchup, David knew he needed to move quickly. He ran at the great man, reached into his bag, and with his sling, threw one perfectly aimed stone from a great distant. Within seconds, the fight was over. Goliath pitched forward, stunned by the blow, and while he was on the ground, David cut off his head—with the man’s own sword.

If confidence is knowing your strength, humility is an awareness of one’s own weaknesses. David possessed as much humility as he did confidence. It must be said first that he never sought out this fight—he’d have preferred that the army took care of it. He’d probably have preferred the war never need to take place at all. Once the challenge came his way, however, and he saw that no one else was doing anything, he asked himself what he might do if he had to. David knew that he was too small and weak to fight in traditional armor. He could see how it slowed him down. He knew that his courage was hardly sufficient to compensate for the massive size differential and that his lack of fighting skills made a direct challenge next to impossible. He knew that if Goliath got his hands on him, it was over, that his flesh would soon be fed to the birds and animals. Yet also aware of his skill with the sling, he knew he had an advantage. If he could get one shot off, time it right, there was an opportunity. He was confident enough to take it.

It is here that David’s faith also plays a role. Just as his belief gave him confidence, it also makes him humble. He sees himself as a servant of the lord, and also a servant of his king. He believes he’s been called to answer this challenge—his will is strong because it’s not his will—but conversely, if he were to lose, he would see that as being God’s plan as well. In a sense, he’s willing to proceed knowing full well that it could go horribly wrong for him. There is real humility, real courage in that.

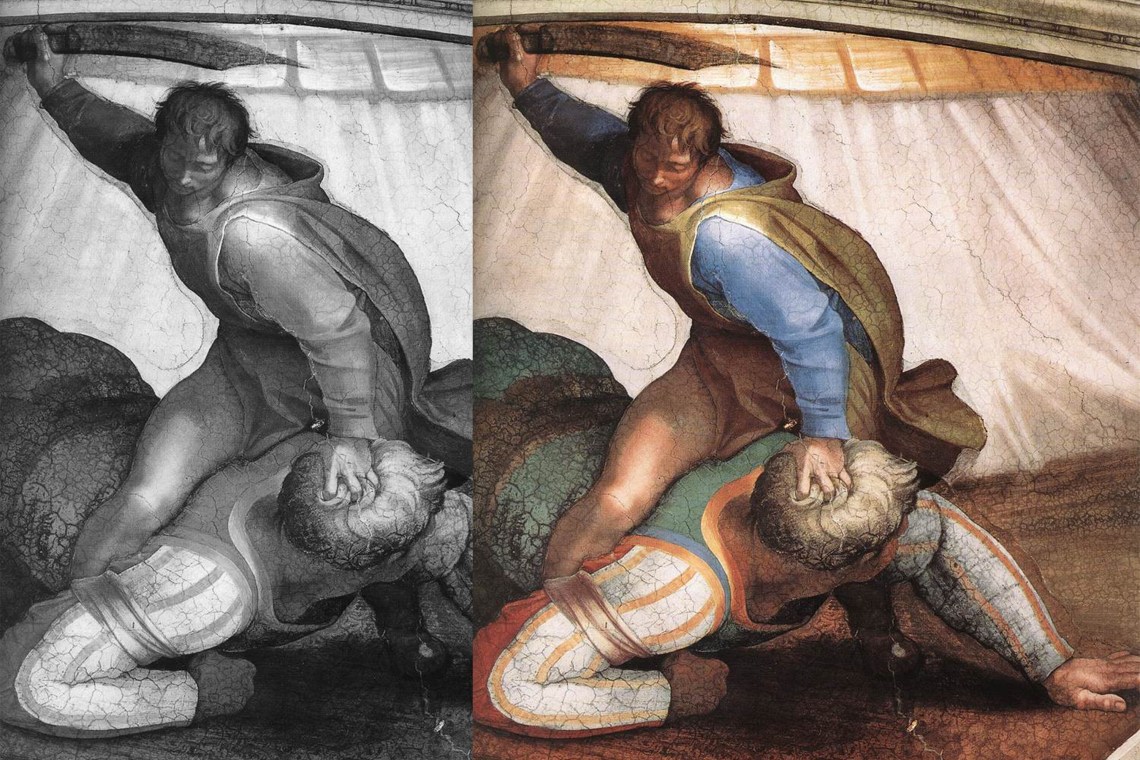

In Caravaggio’s great painting of David with the Head of Goliath, there is a detail that most people miss. The painting shows David holding Goliath’s head in one hand and his sword in the other. On the hilt of that sword, in small lettering, is the acronym, H-AS OS, humilitas occidit superbiam. Humility Kills Pride. Pride is a sin for a reason—because it makes us think that we are better than God, or than other people. Humility kills ego as well. Or rather, humility and confidence, in concert with each other, are an unstoppable force.

Another great fighter and champion, Frank Shamrock, would say many centuries later, that ego is a sort of false idea, a kind of mental garbage. “If you’re running on ego,” he said, “you aren’t running on good clean emotions or cause and effect.” Is that not the story of all great boxers? The scrappy underdog beats the overconfident champ, only to become the overconfident champ who is defeated by the next scrappy underdog? “Champ-itis” is what they call it. That was the problem for Goliath, and the moral of his story. He had gone far beyond confidence, he had gone well into pride and hubris. For forty days, twice a day, he was right. No one could beat him. He was invincible. An entire army cowered in front of him. But like the famous story of the turkey, it only took one day to change everything.

David’s life changed too. His quiet confidence, his creative humility not only made him victorious over Goliath but soon enough it would make him king. The moral of David’s story is there to counteract that timeless worry, expressed so well by the Reverend Dr. Sam Wells, that if we are humble, we will end up “subjugated, trodden on, embarrassed, and irrelevant.” In fact, humility makes us powerful and it can be the source of great strength. As for David it transformed from servant to leader, challenger to incumbent. One can imagine he soon felt the pull and corruption of ego once he held power, putting him firmly in the shoes of Goliath and Saul…as it always seems to go. And so in this way, ego is always the enemy—of who you are, where you are going, and what you want to do.

The reason the story of David and Goliath survives is not simply because it is the tale of the underdog, which we all love. It survives because it is the rich interplay between the traits and virtues every person must wrestle with in their own way in their own life: Where does my confidence come from? What does it mean to be humble? How can I avoid the dangers of ego and hubris?

The answer is in the text if you look for it: It’s that we need confidence or we are weak and afraid. We need to be wary of ego because it makes us vulnerable and self-destructive. Most of all, we need humility to guide and direct us. And these three variables are in constant flux and flow with each other, bringing us success and honor and heroism when they are in balance but pain, suffering and disaster when they are not. ![]()