How On Earth Did Bob Dylan Approve ‘A Complete Unknown?’

Moira Rose’s favorite season is upon us: Awards! That means that YouTubers, culture critics, and your good friends at Thought Catalog are about to be very busy. There’s just so much to discuss and so little time.

That said, among these developments up for discussion is Timothée Chalamet’s performance in A Complete Unknown, which is so lifelike as to be uncanny. Chalamet gets the reclusive singer’s look, voice, and gait down pat, and perfectly captures Dylan’s movie-long transition from shy asshole to confident asshole. It’s a brilliant portrayal of a brilliant artist and delivers satisfying entertainment at every turn. On the other hand, the movie around him is a surprisingly conventional way to depict a famously unconventional person.

That’s not to say I’m knocking the movie. A Complete Unknown is a rousing, moving film, heightened by poetic dialogue and, of course, Dylan’s music. But back in 2007, when director Todd Haynes directed that other Hollywood Bob Dylan biopic – the experimental, controversial I’m Not There – Dylan said that he wouldn’t have approved any other screenplay. And yet, here we are. In terms of its format and conflict (standard three act drama; Man vs. Society) A Complete Unknown is far more conventional and far less revolutionary than either I’m Not There or Dylan himself. However, the singer supposedly gave A Complete Unknown his stamp of approval after doing a readthrough with director James Mangold. What gives? Has Dylan lost his edge?

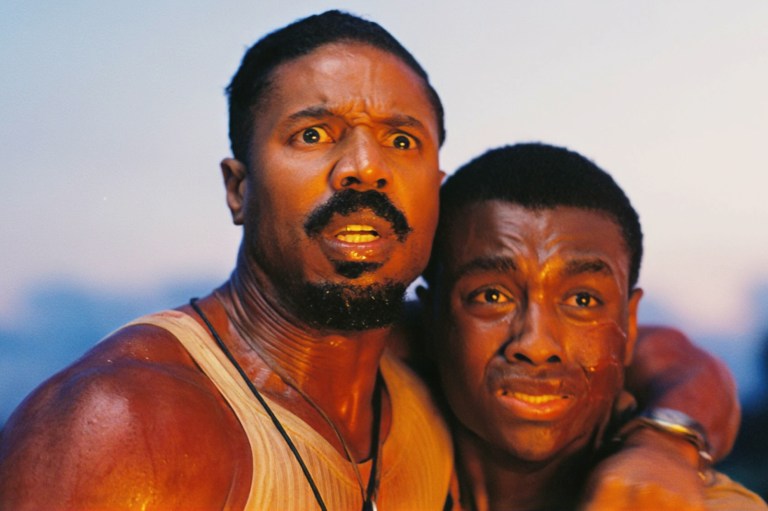

Perhaps it behooves us to describe I’m Not There a bit further, in case you didn’t catch this uniquely complex curio from the mid-aughts. I’m Not There is a non-linear “experimental biopic” that examines six aspects of Dylan’s life through the lens of six different fictional characters – none of whom are named Bob Dylan, and each of whom is played by a different actor. In this way, the movie is a prism, refracting Dylan at six different angles and into six different horizons. Christian Bale plays “Jack Rollins,” who embodies Dylan in his first years of stardom, when he leans into folk music and rages against capitalism. Heath Ledger portrays an actor, Robbie Clark, tasked with playing “Rollins” on screen. In doing so, Clark upturns his life and becomes a cipher for Dylan’s real-life marital difficulties. Meanwhile, Marcus Carl Franklin plays “Woody,” an 11-year-old Black version of Bob Dylan representing the artist pre-fame and at his most vulnerable; at this point, he’s trying to survive and honor his artistic inspirations.

On the other hand, Ben Whishaw (Q from the latest Bond movies) plays an enigmatic and fitfully poetic version of the singer named “Arthur Rimbaud” – perhaps the movie’s closest approximation to Dylan’s public persona, or at least the one he adopts in interviews. Rounding things off, there is Richard Gere as “Billy the Kid,” a reclusive old man and a metaphor for Dylan later in life. And last but not least, there is Cate Blanchett – yes, that Cate Blanchett – as Jude Quinn, a rebellious, electric-guitar playing wunderkind who typifies Dylan at his most charismatic. Blanchett earned an Oscar nomination for this mesmerizing performance. In the movie, no one ever draws attention to the fact that she is Cate Blanchett.

I’m Not There is a hypnotic, kaleidoscopic, scintillating, titillating, confounding piece of art – a perfect send-up of a man who has defied explanation and avoided scrutiny for the better part of his long life. A Complete Unknown is a straightforward, crowd-pleasing story with familiar faces and an empathetic central performance. (Chalamet does give Blanchett a run for her money, though.) So, again, what gives? Why did Dylan suddenly decide that I’m Not There was no longer a sufficient encapsulation of his dreams, fears, and failures? Did he perhaps want to make his music more accessible to younger audiences? Was he attracted to the theme of rebellion inherent in A Complete Unknown, which hones in on Dylan’s transition to electric guitar?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind. But as we try to grasp at it, you may as well take this as an opportunity to revisit Dylan’s music. No movie will ever convey the rapturous, furious concessions and objections of his lyrics, so you may as well just appreciate them in their intended context. And while you do that, I will be off somewhere trying to turn Timothée Chalamet gay.