McDonald’s Just Brought Back Monopoly – But Its Dark $24 Million Mob Crime Past Still Lurks Beneath Every Peel

By Erin Whitten

McDonald’s revealed on Sept. 29, 2025, that after a 10-year hiatus, the Monopoly game is back at restaurants in the United States, this time with digital integrations, new prizes and a whole lot of nostalgia about “remember the thrill of the peel.” The truth of why the game was gone for a decade has nothing to do with marketing or consumer desires though. Its absence is a direct result of an absurd scandal that took over a decade to unfold. It’s the kind of heist movie plot that Hollywood wouldn’t dare put on screen, mobsters and psychics, strip-club owners and cocaine dealers, an ex-cop smuggling away stolen tickets in a custom vest, and an FBI sting so elaborate it would make Donnie Brasco blush. If you binged HBO’s McMillions docuseries, you know some of the saga – but the truth is darker, stranger and juicier than most people know.

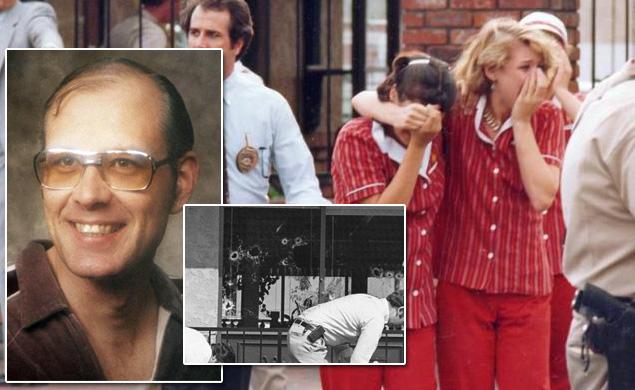

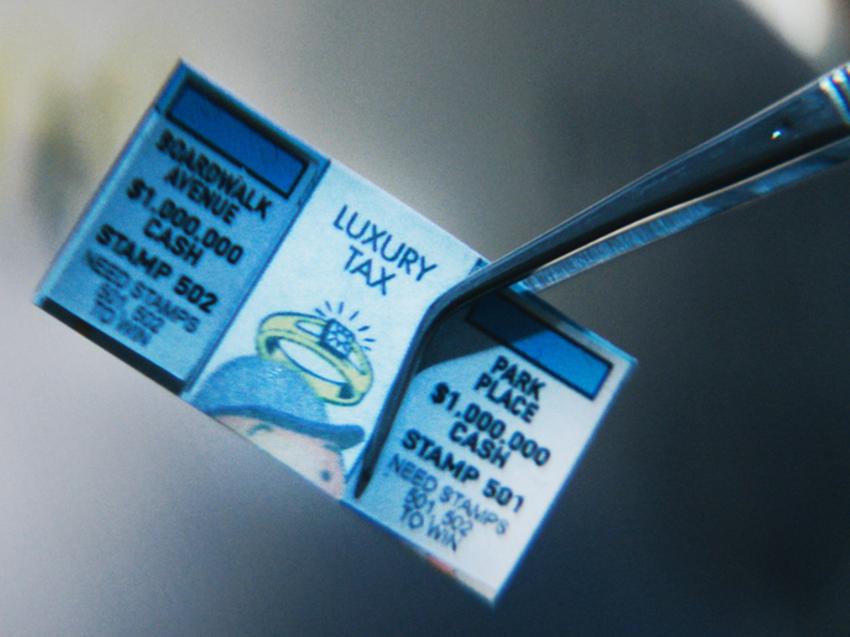

The cast of crooks and ne’er-do-wells all trace back to Jerome “Jerry” Jacobson, a former Florida police officer who never quite graduated from probationary status after a medical issue. He reinvented himself in the private security business and worked his way into the head of security position for Simon Marketing, the firm hired to run promotional games for McDonald’s from the early ’80s until the early ’00s. Jacobson’s job was simple, secure all of the winning game pieces in his office, oversee the staff that sealed them into envelopes, and fly them on his company plane to various factories where they were affixed to fry boxes, soda cups, and magazine inserts.

Jerry Jacobson found a major vulnerability almost by accident. A supply-chain employee mistakenly shipped him those heavy-duty metallic seals used to close the high-value envelopes. With access to the seals, Jacobson could open any envelope, swap a winning piece for a worthless one, and reseal it so the switch wouldn’t be obvious. He smuggled the stolen winners inside a vest he wore on his plane – leaving all of the customers with nothing but false hope.

Jacobson tested his new system first by giving winners to family members. His stepbrother Marvin pocketed $25,000. A local butcher in Atlanta once gave Jacobson $2,000 in exchange for a $10,000 winning piece. When those early gambits were never challenged, Jacobson’s appetites grew. He started diverting million-dollar winners and hoarding them in safety deposit boxes, and when he got around to it, taking his cut before deciding which “lucky customer” would be allowed to claim the prizes in exchange for a price. As the scam continued into the 1990s and early 2000s, his list of fake winners ballooned far beyond his network of friends and family.

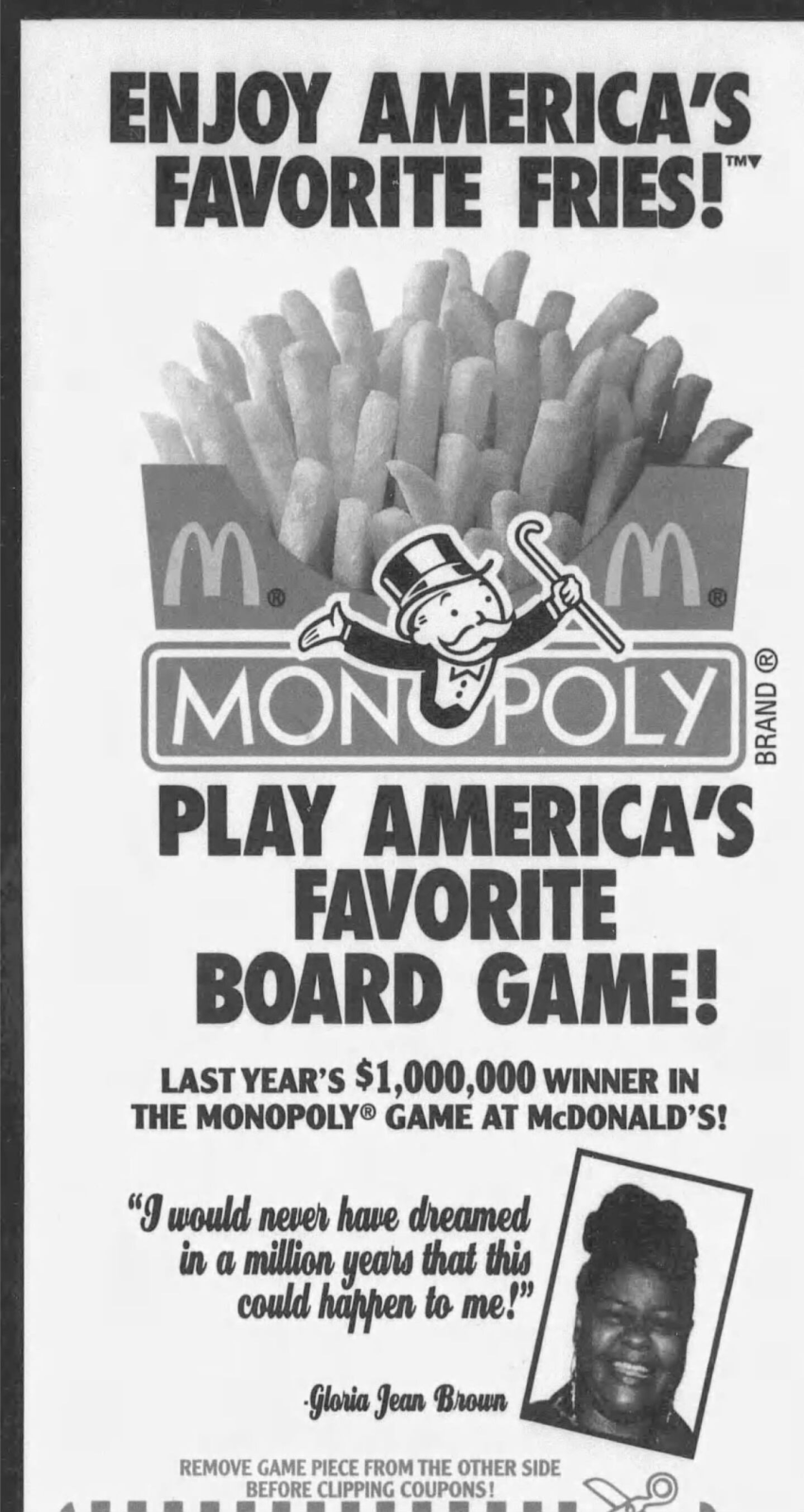

Jacobson’s ring turned into a rogues’ gallery of American hedonism. One of his earliest and most flamboyant recruits was Gennaro “Jerry” Colombo, a South Carolina strip-club owner who liked to brag about his ties to New York’s Colombo crime family. Colombo loved the attention he was getting from his wins, and happily waved a giant Dodge Viper car key for a McDonald’s promotional video. Like most winners, he quietly opted for the cash. Colombo brought in his wife Robin, her father, and even her best friend to “win” million-dollar prizes after purchasing tens of thousands of dollars in stolen tickets. Gloria Brown, for example, met Colombo on the side of I-95 in South Carolina to exchange $40,000 in cash for her winning piece. He coached her on exactly what lies to tell about where she found it, including a fake South Carolina address to cover her tracks.

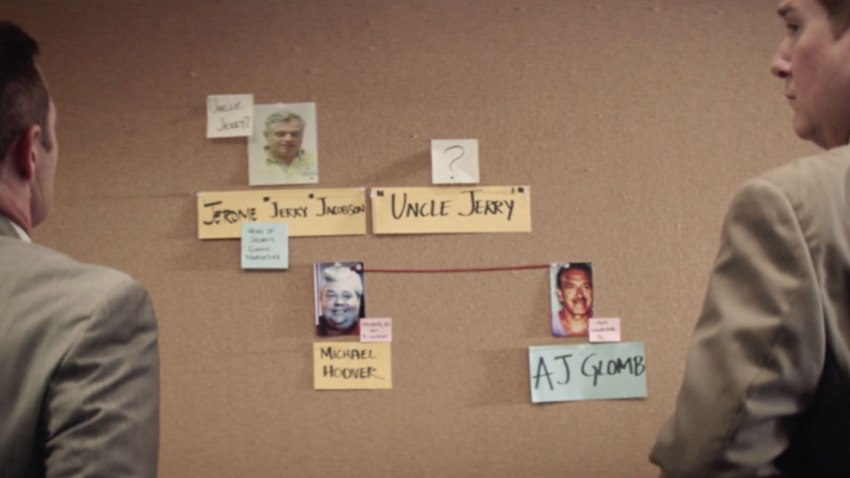

Colombo wasn’t the only person Jacobson tapped to help scale his operation. Jacobson brought on Don Hart, a trucking magnate, who in turn introduced Jacobson to Andrew Glomb, a convicted cocaine trafficker, who distributed stolen tickets to his old criminal network. Among other winners were psychics, strip-club operators, and random people selected from parties or just handed a winning ticket on the street or at Mardi Gras parades. Jacobson’s empire grew exponentially, and at its peak, almost every single big prize, cars, cash jackpots, trips, was claimed by a winner with a hand in the scam. Regular customers never had a chance.

What brought it down was one of those random tips to the FBI. In 2000, someone called and said that “Uncle Jerry” was running a scam rigging McDonald’s Monopoly. Special Agent Richard Dent, based out of Jacksonville, Florida, opened “Operation Final Answer” and started connecting dots. He quickly noticed geographic patterns like clusters of winners from the same towns, almost all with links to Jacobson’s lake house in South Carolina. McDonald’s agreed to conduct a new Monopoly promotion under FBI surveillance, allowing agents to track winners, intercept phone calls, and even send a team to pose as a McDonald’s film crew making a commercial. One of the most surreal moments of the sting involved agents filming Rhode Island man Michael Hoover, a cook coached into claiming a million-dollar prize. On camera, a nervous Hoover told a preposterous story about a lost People magazine falling into the ocean, and his buying another copy that magically contained the winning piece. The agents watching from behind the lens knew that they were recording a lie in real time.

In August of 2001, the FBI raided the national network and Jacobson was arrested at his home in Georgia. A total of more than 50 people were eventually convicted in the scam altogether. Jacobson himself admitted to stealing at least 60 winning pieces, worth more than $24 million in prizes. He received a shockingly light sentence of just 37 months in prison for the largest-ever theft from a McDonald’s promotion. His network of recruiters received sentences ranging from probation to short prison stints.

The trial’s timing meant that the story never registered with the public. Jury selection started September 10, 2001, and within a day, 9/11 swept every news cycle. The McDonald’s fraud, was effectively placed in a deep freezer. McDonald’s – keen to limit reputational damage, spent $10 million on a promotional giveaway to save face and quietly severed ties with Simon Marketing.

With the game’s relaunch in 2025, McDonald’s Monopoly will be equipped with technological protections using its app, property tracking and verification systems to prevent another “Uncle Jerry” from emerging to secretly stack winners. For all the pretty advertisements and shiny prize boards, it’s easy to forget Monopoly’s history was once both extremely weird and very, very seedy. It was a tale of mobsters and middlemen, swindlers and civilians drawn into the orbit of a former cop who pocketed game pieces in airport bathrooms and constructed a pyramid of counterfeit millionaires. Now, as McDonald’s invites us to peel again, it’s hard not to wonder if the real jackpot was always the story hiding behind the fries.