The Joy Of Thinking (Differently)

The universe becomes uncanny at its core, always shifting and realigning depending on how you look at it.

Here’s an easy exercise. Look around the room and choose anything you see, anything you think of. Me, I’m looking at my set of keys.

Now start listing all the ways this thing — my set of keys — can be categorized, thought, imagined, all of its uses, all the ways it connects to other things. My keys, for instance, are little knives; symbols of discovery; symbols of enslavement; a literal weight on me; a plethora of opportunity and possibility; the limitation of my possibilities; envelope and box openers; a child’s toy; a dangerous child’s toy thanks to the lead; a collection of like things; a security blanket when I’m out and about, that jangle and jab tethering me to place and vehicle; the history of keys, of secrets, of private property; children’s games of secret passageways; a sign of adulthood (my beast does not carry keys; at what age will he have his own key, I wonder).

What else?

Each thing — visible and invisible — exists within multiple categories, multiple series, multiple networks. Most things have a more or less prescribed use: this is what you do with keys, silly man, you open doors.

Inventors, of course, find different uses for known things. This is amazing: they find life, extend the thing, create new worlds from the old world. It is nothing less than a miracle.

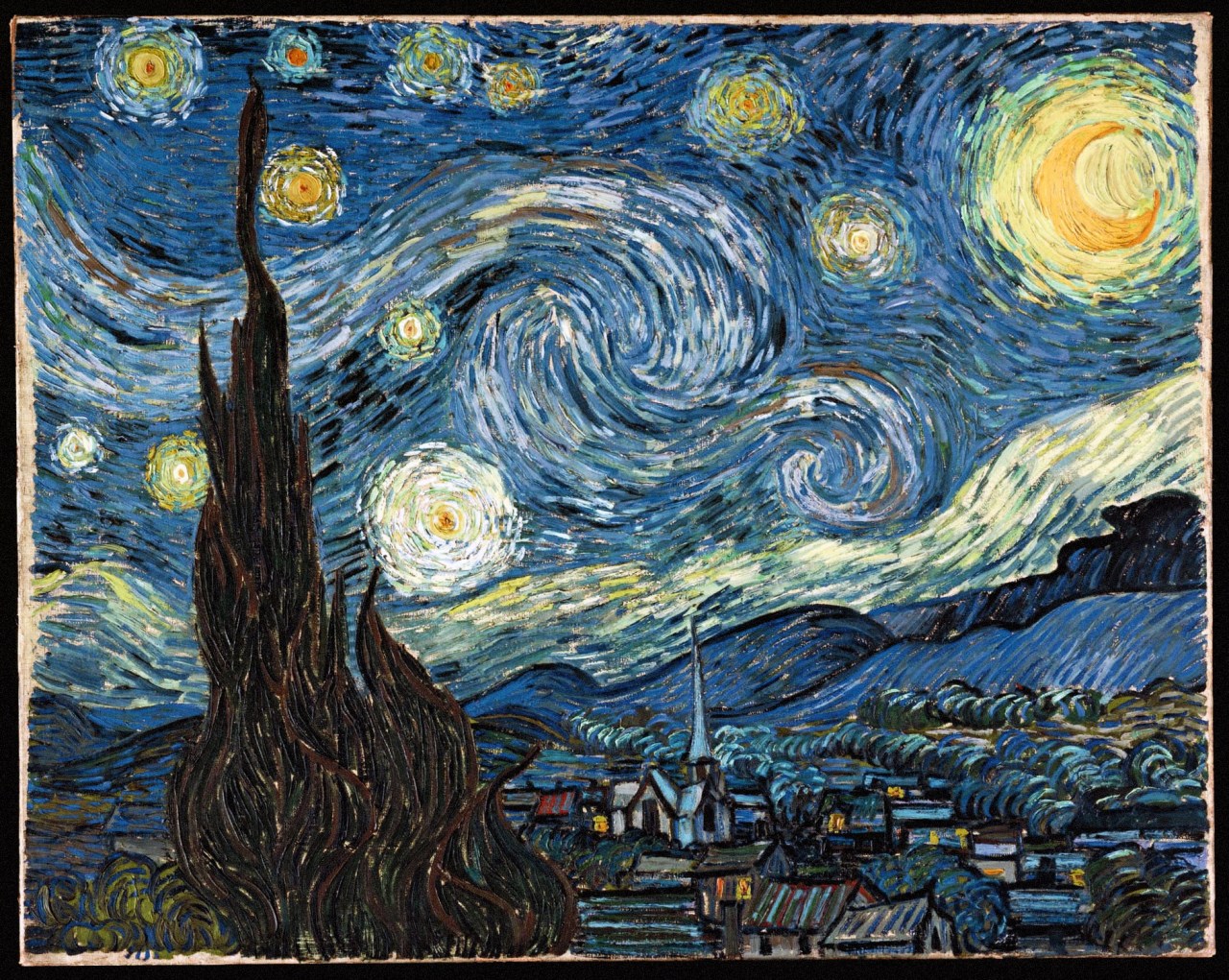

Artists do the same: they literally have us see anew. Take something as simple as Starry Night: doesn’t Van Gogh teach us to see the sky — something we see everyday — again and anew, as if for the evry first time?

Reading — interpreting, perhaps, but I don’t like that word for a number of reasons — can do the same thing. It can take a known object and make it unknown and then known again as something new. It is truly incredible: I can read some words on a page that make me see something I’ve always seen, understand something I’ve always understood, as if seeing it for the very first time. What was dead is summoned to life, to new life, to new possibility.

This is the way I experienced when I first read Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality v1. I was someone who believed that sexuality was a vital force that the powers that be repressed, beginning with the Victorians. Such and such culture or such and such historical period were certainly more liberated than we are. Indeed, like so many others, my understanding of sexuality was defined by the figure of repression/liberation.

Until I read Foucault who told me that repression was, in fact, another form of power — that power does not only restrict, it constructs. Look, Foucault says, look at how often and how much the so-called repressed Victorians talked about sex — relentlessly. They were so obsessed with sex they covered the legs of pianos out of discretion.

Oh, man, when I read that the whole world yawned anew. To have such a hallowed idea, an idea that I didn’t even realize I had because I simply thought it was true, to have such a thing so completely re-organized, redistributed, a whole new sense of it forged was invigorating, intoxicating, making me delirious with possibility. The whole world — every thing, every idea, every person — could be read from multiple angles and perspectives, redistributed and recast and repeated and become something new. The universe becomes uncanny at its core, always shifting and realigning depending on how you look at it.

To think different, to think differently, is to create life. It is the ultimate joyful act — to read critically is to perform Whitman’s great line: urge and urge and urge/always the procreant urge of the world.

If all things are multiple, are nodes with different series, then to forge or discover these series is to breed life. ![]()