The Real Horror Of Hulu’s ‘Good American Family’ Goes So Much Deeper

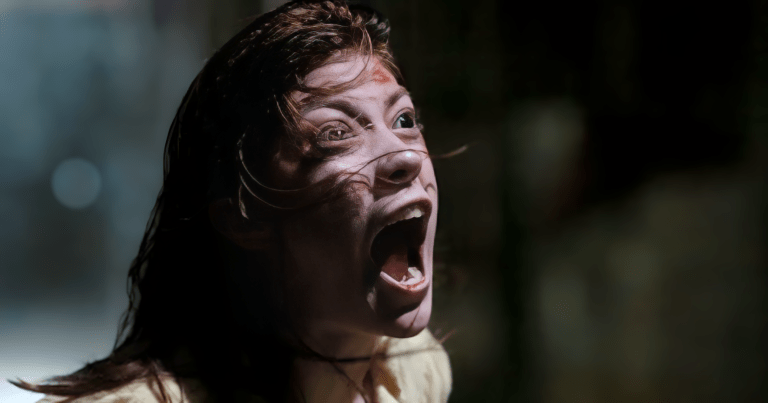

There’s a type of horror that doesn’t come with jump scares or bloody crescendos.

Instead, it shows up in broad daylight, with khakis and cul-de-sacs, PTA meetings and perfect smiles. Hulu’s Good American Family is exactly that kind of horror. On the surface, this limited series chronicles the story of Natalia Grace and the Barnett family, the Indiana couple who adopted a Ukrainian orphan and later accused her of being a grown woman masquerading as a child. But the real horror is how the story is told. The narrative choices aren’t just editorial decisions, they’re moral ones. And, whether intentional or not, they quietly tell viewers who to believe, who to fear, and who to blame.

When The Myth Comes Before The Truth

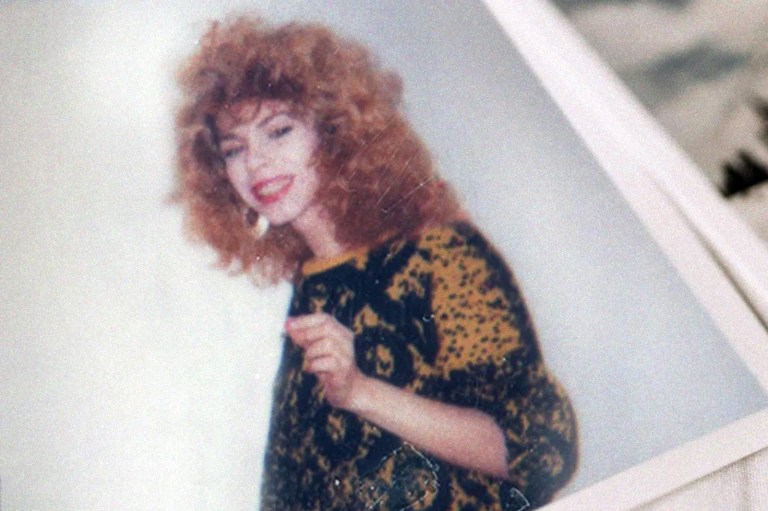

From its title alone, Good American Family is loaded with irony. It conjures Norman Rockwell paintings, church picnics, and the whole white-picket-fence fantasy. But that image cracks almost immediately. The Barnetts are introduced as the all-American dream team led by Kristine, the energetic, overachieving mother, and Michael, the gentle, agreeable dad. They show us photo albums and videos showcasing happy times with their three sons.

For a moment, we’re almost lulled into seeing them as sympathetic. And that’s the problem. The show begins squarely in their corner. We see Natalia through their eyes first as strange, suspicious, and ultimately dangerous. This child with dwarfism becomes the creepy outsider in their perfect world. She doesn’t smile enough. She doesn’t act grateful. She’s different. And that difference is painted as a threat before we ever hear her speak her truth.

By the time the story moves on to Natalia’s perspective, the damage has been done, with viewers conditioned to see her as the villain of this twisted fairy tale. That’s not just a creative choice, it’s a moral failure. Because when the voice of a vulnerable child is withheld until later episodes, it reinforces the very narrative that turned her into an object of fear in the first place.

Natalia Was Always More Than A Twist Ending

One of the most disappointing things about Good American Family is how Natalia is used more as a question mark than a person. For most of the series, she’s more of a symbol than a person. She’s framed as the problem child, who disrupted the Barnetts’ self-made illusion of goodness. She’s also foreign, disabled, and doesn’t perform the role of grateful adoptee the way Kristine wanted. And for that, she becomes their scapegoat.

That is the show’s central thesis, whether it wants to admit it or not. When someone threatens the myth of perfection, the system will do whatever it takes to erase them. We need to talk about how that myth is propped up because it’s not just about Kristine sobbing in front of a camera. It’s about how the media still loves the story of the white savior parent, the struggling orphan, and the miracle of adoption. But when the child doesn’t fit, the frame gets changed, and the child gets discarded.

The Show’s Ambiguity Is The Most Chilling Part

To its credit (or maybe to its detriment), Good American Family doesn’t give us clean answers. There’s no big reveal that ties everything in a bow. The series presents the Barnett’s version of events and Natalia’s later rebuttals and lets viewers decide where they land. But that kind of “balanced” storytelling can be dangerous when it pretends both sides hold equal weight. By giving more airtime and emotional space to Kristine Barnett early on, the series gives her suspicion legitimacy it doesn’t deserve.

And even when it shifts toward Natalia’s side of the story, the framing still subtly questions her credibility, despite the legal outcomes and DNA evidence that back her up. We can’t pretend storytelling choices don’t matter. They do. Especially in a true story where one side is a child who was abandoned in an apartment, and the other is a family that legally changed her birth year to avoid parenting her.

The Real Story of Natalia Grace

Natalia Grace was born in 2003 in Ukraine with a rare form of dwarfism called spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita and was given up by her birth mother because of it. She was adopted by Kristine and Michael Barnett in 2010. A few years later, they decided she wasn’t really a child and petitioned a court to legally change her birth year to 1989, making her 22 on paper. They moved her into an apartment and left the country. But Natalia wasn’t an adult. She was a little girl.

A court-appointed expert confirmed it in 2023 using epigenetic age testing. The charges brought against the Barnetts for child neglect were ultimately dropped, but the facts of what happened remain disturbing. Natalia was failed, first by the people who were supposed to care for her, and then by a system that debated her identity instead of protecting her humanity. Now, Natalia lives with a loving family. She’s pursuing her education and speaking about the abuse she suffered in her own words.

The thing about true stories is that they need to be told with care, and Good American Family doesn’t always do that. It’s entertaining, narratively complex, and even socially insightful. But the one glaring mistake it makes is sacrificing clarity for suspense. It treats a child’s trauma like a puzzle to be solved instead of a tragedy to be mourned. We can’t keep turning real people into plot devices. Especially not when those people are already marginalized, already voiceless, already fighting to be seen.