A Word For Those Who Don’t Understand Anxiety

"...He was stuck in his brain, and couldn’t find the way out of his mental hell."

I love my mother-in-law. Not many people can say that about their in-laws. But I’m a lucky one. She’s a naturally gregarious and gracious woman who always makes others feel at ease, and has raised three very smart, solid children with the help of a conscious, thoughtful husband—and after 30+ years, they genuinely love each other.

They are the model and legacy that I want for my husband, myself, and my family in this lifetime.

I, on the other hand, come a very dramatically different family dynamic.

I would like to interject very quickly and say that my M.I.L. (mother-in-law) is a fan of the T.V. show “Modern Family.”

Like most kiddos in the 90s (and many today), my parents were separated in 1994 and divorced in 1996. Divorce is nothing new; but the circumstances always vary.

My dad had cheated on my mom from the 15 of the 19 years they were married—but I’m glad they are divorced: they couldn’t be two more of the opposite people (she, a Republican female executive powerhouse; and he, a liberal, hippie, economist moving from city-to-city every six months).

I was never “woe-is-me” about my parents’ divorce—though I’m sure my mother would argue otherwise during the natural teenage angst years. The only thing that ever bothered me about their legal separation was that my father left five children under 18, married two weeks after he divorced my mom to a woman he barely met online, and moved away to Pennsylvania to have “the life he’s always wanted.” (They divorced five years later, and still searching for that unattainable dream life.)

Here’s another thing: There’s a five-year gap in-between my siblings. Meghan, Danny, and Paul are roughly 10 years my senior, so when my parents divorced, my younger sister (by less than two years) and I stuck firmly by each others side.

Still, the age difference never bothered me. Molly and I speak our own language through our shared experiences and generation (thanks, Pepsi!), love of the cancelled ABC Family “The Brenden Leonard Show,” and admiration for Glassjaw, Coheed and Cambria, and other nostalgic screamo delights.

The same year my father moved away in 1996, my grandfather Arthur passed away from a heart attack and my grandmother Dorothy moved into our home. Before moving in, my grandfather helped with our big brood: helping to make lunches, running the carpool, and dealing with the emotional chaos of five, wild children as my mom worked her ass off to make ends meet.

Even still, I would still like to say that I never had anxiety through my childhood. I had a very solid group of childhood friends at a small elementary and private school; I was very active in my then-Catholic community, and was one of the top students throughout public high school as a proactive as Publicity Lead of Masque and Gavel (a.k.a. drama club, Latin club, and journalism).

My childhood attitude was: “This is life, everyone. Deal with it.”

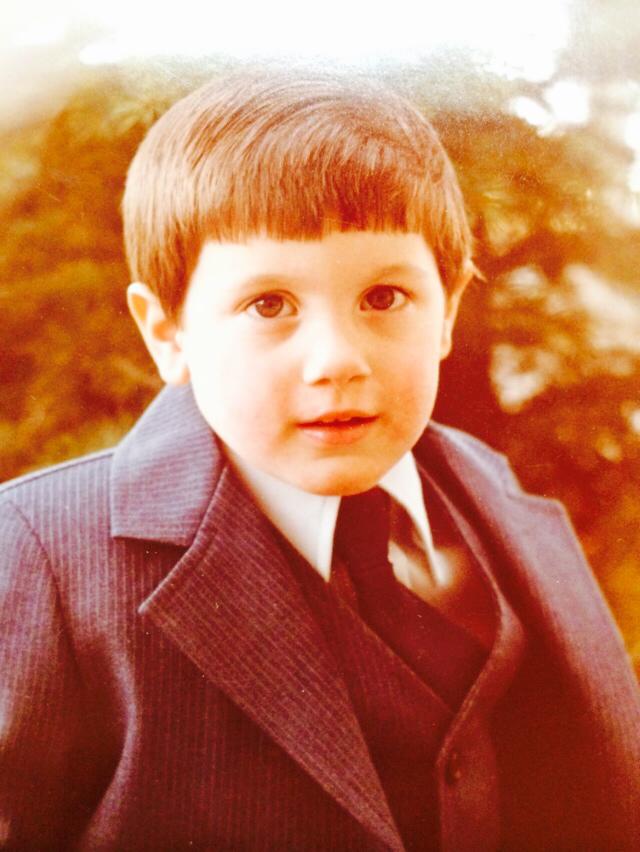

However, my oldest brother Danny dealt with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Bipolar Disorder throughout these life changes. I always thought of about “nurture vs. nature” when Danny was at the pique of his struggles. I thought he was so dramatic and insecure; I naturally blamed it on the nature of my parents’ divorce and thought prescription medication was an absolute joke.

I was a walking, talking, breathing voice: “Just deal with it, Danny. They’re emotions. Just deal with it.”

Even with Danny’s anxiety, I knew that with the support of my ever-positive mother and other siblings, that Danny would overcome his anxiety, and it was just something that happened in your 20s—it’ll pass. Someday, I’ll get to know “the adult” Danny.

But his self-consciousness got the best of him with every passing year, and the drugs that he was prescribed—the Xanax, the benzos, the morphine, the whatever else to calm him down—began to get the very worse of him and took him to another level. Many other levels.

He had been to attend rehab a few times for his addiction to prescribed medication. He once stole money from random gym locker rooms, would joy ride cars in those gym parking lots, and even took his new silver Honda Accord and crashed it into a house—high as a kite. He went to jail a few times which crushed his confidence even more—naturally. He lived in a halfway house. Many halfway houses.

He was stuck in his brain, and couldn’t find the way out of his mental hell.

And that mental hell was causing my mom pain, my sisters pain, his best friend and brother, Paul, pain. Everyone pain.

“What a selfish asshole,” I always thought. “Think about someone other than yourself. It’s not that difficult.”

This is what I thought of Danny — perpetually.

Still, when I was young and in my teens, I didn’t have anxiety and wasn’t even close to comprehending it. I didn’t respect my older brother Danny. I simply judged him on the fact that all these so-called dramatic actions were a result of my parents’ divorce, and that he simply needed attention, never wanted a job, and needed to grow up.

After I graduated high school in Tempe in 2003, my mom was offered an executive job in Houston and I moved with her. That way, I could support my youngest sister, Molly, and she could finish high school without being alone, and we could attend the University of Arizona together the next year.

It was when I was 20, our first year in Houston in 2005, that I was driving the car with my mother. My phone rang and my Dad was calling me. He originally called my mother, whom we both laughed at and ignored him, when he first rang for me.

“Dad, Mom and I are busy—”

“Brighid, I need to talk to your Mom. Tell her to pull over the car.”

I tried to talk him out of it (chalking it to dramatics) until a biting tone finally gave way to hand the cell phone to my mother.

When Mom pulled over the BMW in a brand-new school and its empty school parking lot; it was her heaving hysterics that I couldn’t decipher when Dad starting talking to her through my many “what’s going on?” questions. My mother finally said: “Your brother is not alive.”

Not: Your brother is dead. It was: Your brother is not alive. As if maybe he’ll come back.

We flew to Phoenix immediately, attended the funeral a few days later, and I stayed up the entire night before constructing a eulogy about Danny, my 26-year-old brother who had overdosed on the medication in which he was prescribed for anxiety.

Here’s the truth: I didn’t know Danny, my brother who was seven years older than me. I never respected Danny in my life. He was a mumbling drug addict filled with cheap one-liners, self-consciousness and self-doubt, and was the very person I did not want to be.

He once called me a “good sister” because I loaned him $10 two days before Christmas one year. And I knew he was just going to spend that on drugs.

I was the final sibling of the four to give a eulogy, and I cringe as I think about it because actions speak louder than words and I clearly didn’t know about my brother who had struggled with something purely chemical; nurture vs. nature — and I had always judged nature, thinking he was melodramatic about my parent’s divorce.

After the Catholic funeral where my mother’s brothers tumbled in from all over to orchestrate, my mother’s boss said to me after the funeral: “Your eulogy flowed really well. It had a three-pronged thesis and you followed through with ease.”

I wrote an unforgettable college essay for my brother’s funeral.

Then, my mother’s close friend wrote a sympathy card the following week discussing the heartfelt highlights from the rest of my siblings highlighting personal moments they had shared… except my own.

Today, I am not the confident, judgmental, bitchy, know-it-all, 20-year-old when my brother passed away. On January 7, I turned 30 and my “just get over it” attitude no longer exists.

Over the past 10 years, I have been diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Attention Deficit Hyper Disorder (ADHD), and Bipolar Disorder… I don’t know if I am any of those labels, but here’s what I do know:

I sometimes gets to the point where I can’t look people in the eye when I’m having a conversation. I get lost on the road because my mind races, and I’m afraid that I’m going to hit someone on the road because I cannot concentrate. I then have to park in any parking lot after panic attack passes so I can get my bearings. I cannot focus on verbal conversations like I used to when I was younger. I need to read something in order to understand it. I am not the one to talk; I’m the one to listen. And even so, my mind often wanders somewhere else. Where, I don’t even know. My energy is wasted when I’m around people or useless meetings; and being alone with my thoughts revitalizes myself.

When I was 22, I had a public mental breakdown and briefly ended up in a mental hospital for a week. I care endlessly what you think about me. I am straddling a world in-between self-doubt and wanting to do more, something bigger than myself. I hate my comfort zone, but I love it more than being around people.

When I was 20, I did not imagine myself here—with this personality and these struggles—at 30. But guess what? I’m glad that I’m here…. Sitting at the airport on a business trip writing–finally being open about my anxiety, disorders, whatever.

It has been through the loss of my brother where I have actually gotten to know him and to love him. I take Xanax whenever I need to attend or present for a meeting at work. I take a Xanax whenever I’m in a social situation. I’ve found a prescription that works for me (a daily antidepressant) where I can function and control the severity of my emotions.

No, I am not a drug addict. I’ve just returned managing a project form a business trip that gave me heaps of anxiety to be here. But I’m here for Danny. And for myself. And my future children or niece or nephews who might have anxiety. And especially for you—reading this who probably feels the same way, or for you who has no idea what your loved one is going through.

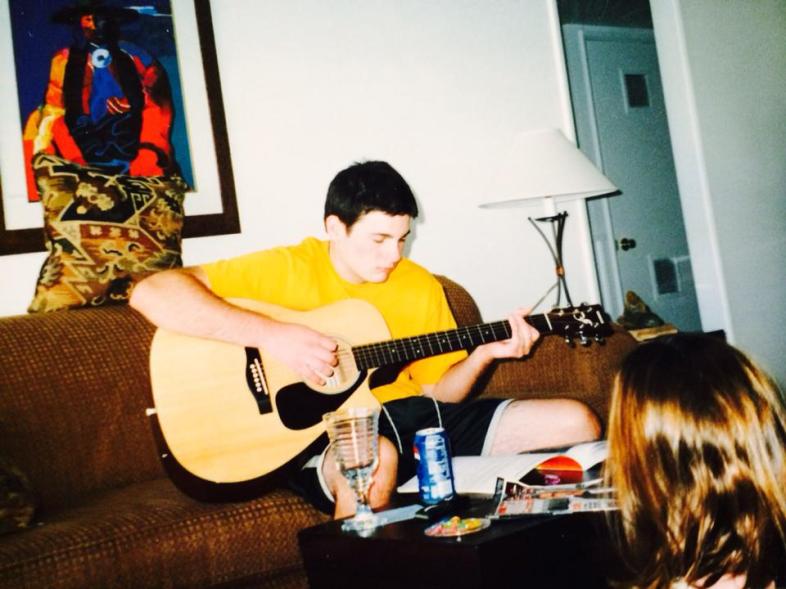

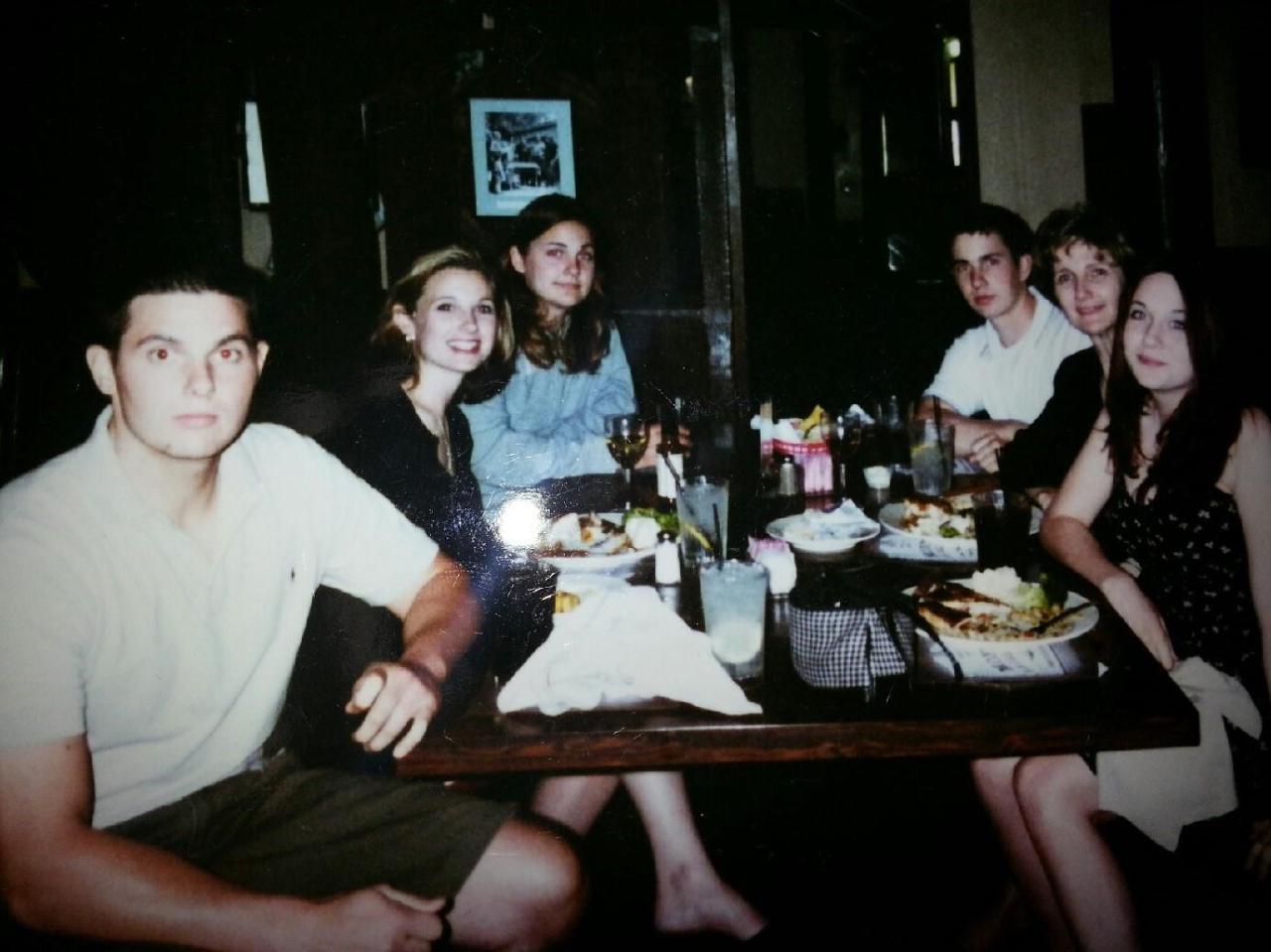

I have isolated myself, like my brother, and through my anxieties I have deeply gotten to know Danny, and deeply gotten to love myself. And I love him for it. I love him for his self-consciousness. For his nervous one-liners. For his quick wit and easy quotes of dystopian novels and adoration of bands like Rage Against the Machine.

So, when my mother-in-law was telling me about that certain someone, and wondered why a certain someone did a certain something because it seemed so simple to her, I felt compassion about the person she was discussing.

But I also felt the need to give people with anxiety a voice.

Because I am the woman trying to make every day work. And it is work. Because Danny was a man with anxiety trying to make his life work. And he didn’t make it.

You have no idea the daily struggles of what anxiety is like… for anyone. Anxiety is not depression. We all have our unique fears, quirks, and distresses; and we’re all here together figuring our lessons out together attempting to be a weird, netted, human support system.

So here’s a not-so-new, but much-needed-to-be-reiterated thought: Instead of judging others, let’s just decide to feed each other compassion.

That’s all I’m asking for no matter where you are: in the workplace, at line in the grocery store, during a seemingly uninteresting interaction—give people the benefit of the doubt about what’s really behind their mind, what they’re coping with, and give them your empathy—give them your love. Not your judgments.

Because you probably made their day. ![]()