My Best-Selling Book Started Off As A Joke: What You Don’t Know About Publishing

All you need to do to publish a best-selling book is take a selfie of your foot. Seriously.

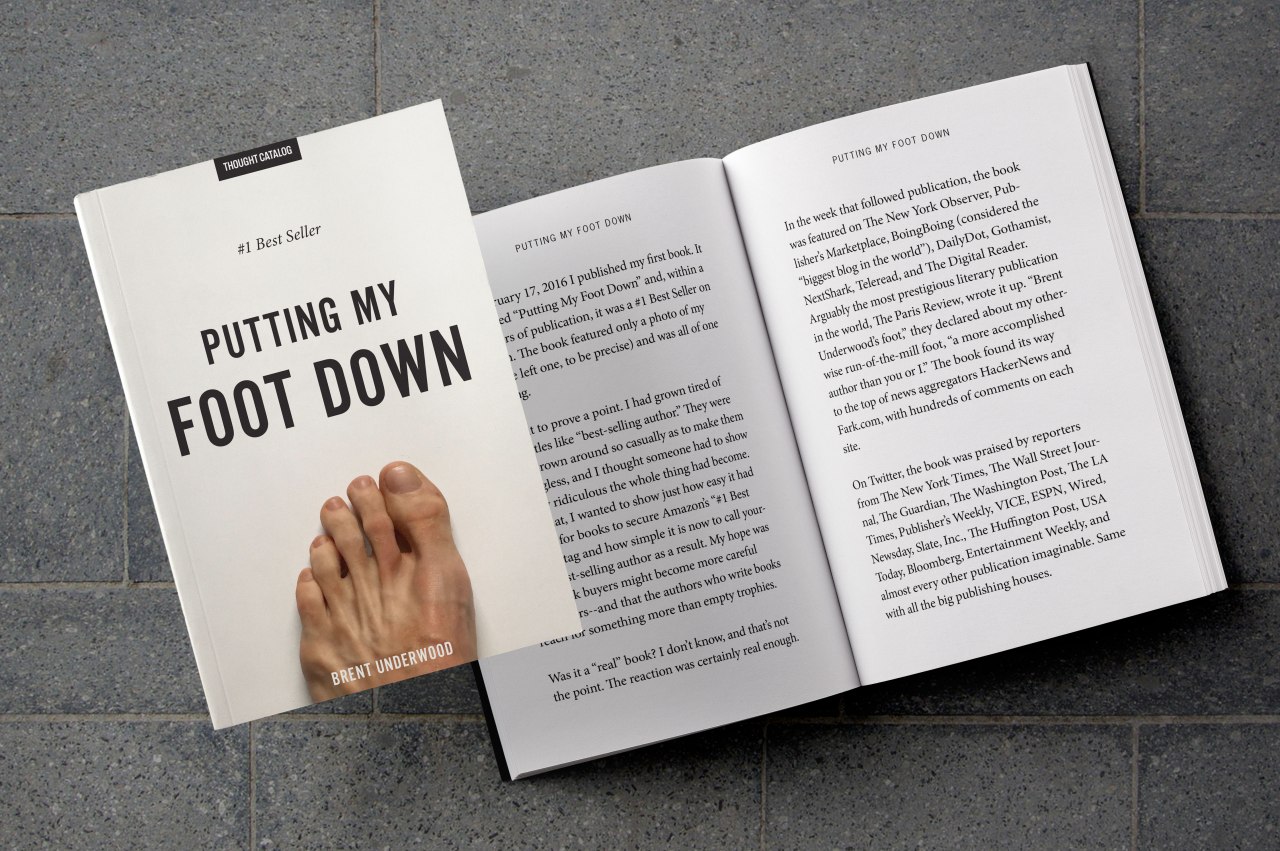

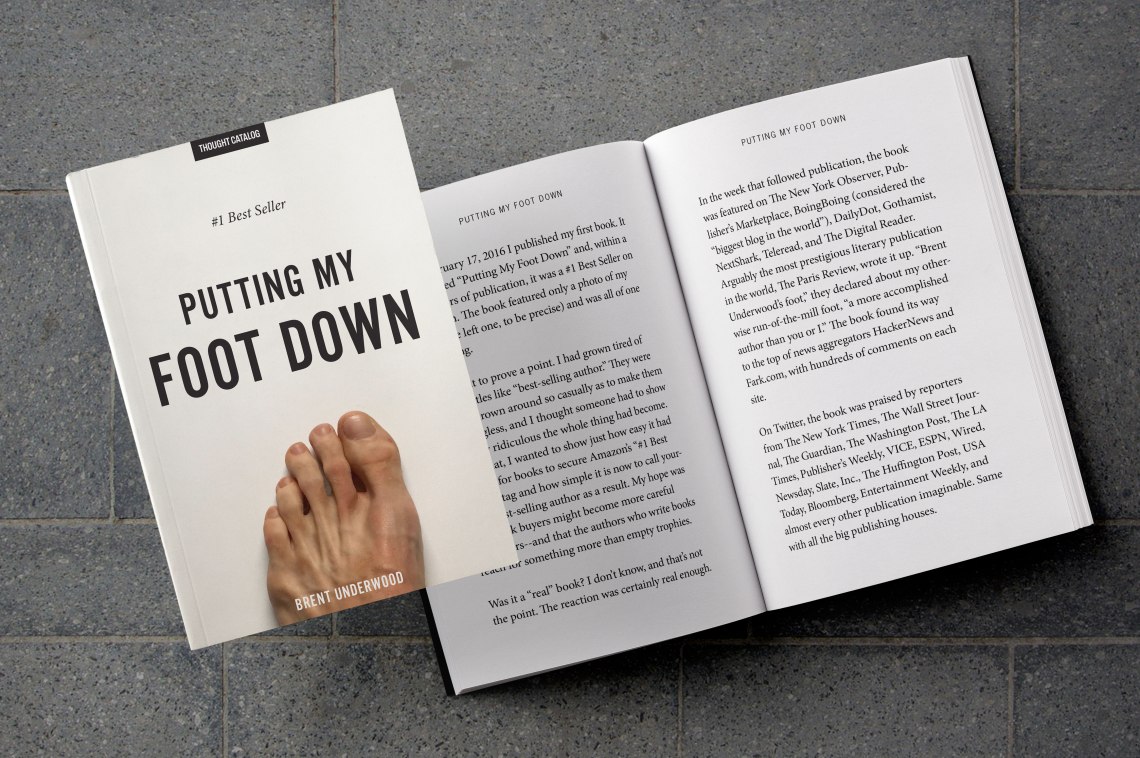

On February 17, 2016 I published my first book. It was called “Putting My Foot Down” and, within a few hours of publication, it was a #1 Best Seller on Amazon. The book featured only a photo of my foot (the left one, to be precise) and was all of one page long.

I wrote it to prove a point. I had grown tired of vanity titles like “best-selling author.” They were being thrown around so casually as to make them meaningless, and I thought someone had to show just how ridiculous the whole thing had become. To do that, I wanted to show just how easy it had become for books to secure Amazon’s “#1 Best Selling” tag and how simple it is now to call yourself a best-selling author as a result. My hope was that book buyers might become more careful customers–and that the authors who write books reach for something more than empty trophies.

Was it a “real” book? I don’t know, and that’s not the point. The reaction was certainly real enough.

In the week that followed publication, the book was featured on The New York Observer, Publisher’s Marketplace, BoingBoing (considered the “biggest blog in the world”), DailyDot, Gothamist, NextShark, Teleread, and The Digital Reader. Arguably the most prestigious literary publication in the world, The Paris Review, wrote it up. “Brent Underwood’s foot,” they declared about my otherwise run-of-the-mill foot, “a more accomplished author than you or I.” The book found its way to the top of news aggregators HackerNews and Fark.com, with hundreds of comments on each site.

On Twitter, the book was praised by reporters from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The LA Times, Publisher’s Weekly, VICE, ESPN, Wired, Newsday, Slate, Inc., The Huffington Post, USA Today, Bloomberg, Entertainment Weekly, and almost every other publication imaginable. Same with all the big publishing houses.

In a sad bit of irony, the book received the kind of outsized attention that only a small percentage of authors manage to get for their work.

* * *

All good things must come to an end, I suppose. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of this press led Amazon to remove my book from the site on February 24th. The reason? The “quality” of it. Or at least that’s what I could surmise from the pre-drafted form e-mail I received when it was taken down. This was the same book, of course, that Amazon had dubbed a “#1 Best-seller” in its category and allowed to be published in the first place. My customer service representative, Adriana S, encouraged me to reach out “If you have any questions regarding our quality assurance review process”. Well, four unreturned emails (two to Adriana, and two to Jeff Bezos) over the next two days, and I had neither answers to my questions nor a book to sell to all my new fans.

My intention with the project was to make a point. It just happened that in this case, I felt that one page was all that I required to make that point. But it was still a book. The package–the container we call “a book”–was necessary for the statement. Certainly, my criticism of bestseller lists would have made less sense as a paper pamphlet or an anonymously published pdf.

Let’s be clear: it’s not as though Amazon has some hang-up about books that might be, ahem, light on the substance. This is the same Amazon, after all, where for the past four years you could purchase the book “What Every Man Thinks About Apart From Sex”, which is 200 pages of completely blank paper. Or this guy’s interpretation of “The World’s Shortest Book” which is just a Table of Contents and a Bibliography with the word “Intrigue!” in between? Who is Amazon to judge any of this? How many pages of writing does a book need to have? How many pictures does a picture book need to have to be considered a real book? If 1 is not enough, is 2? Is it 20? 100?

And what of all the obscene, stupid, poorly written, derivative, or otherwise awful books on Amazon’s platform? Who is to say that the effort of those writers and what they’re trying to say is worth more or less than what I was attempting to say? In a world where other authors can sell books on Amazon that proclaim to help authors sell books–a case of the tail wagging the dog if ever there was one–why should I be punished for actually following their advice?

Remember: absurd art has a long pedigree. Think of Duchamp’s Fountain, a urinal bought as a practical joke among friends, which became one of the most influential works of art of the 20th century. In April 1917, the painter Marcel Duchamp bought a urinal at a plumbing supply store, took it home, turned it sideways, signed it “R. MUTT 1917” and called it Fountain. The piece was rejected from the first art exhibition he entered it in, even though the rules of the exhibition stated that all works would be accepted.

Duchamp’s point was to turn on its head the whole idea of what art is by turning a “readymade” object into art. There was no precedent for this at the time, yet it remains one of those signal moments in the art world. The avant-garde magazine, The Blind Man, put it like this in 1917, “Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.” Challenging the very notion of what is art resonated with the masses and Duchamp’s idea that art should be driven by ideas is the basis of conceptual art today.

Put more simply: some art doesn’t always feel like art, at least not at first. That’s why Richard Prince can sell screenshots of other people’s Instagram photos for $90,000 each. Or a song composed in 1952 with four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence ( 4′33″ ) can become one of the most famous musical compositions of the 1900s and chart on the UK Singles Charts as recently as 2010. Or why Banksy can dominate the media cycle for weeks at a time by doing things like driving around a truck full of stuffed animals. The examples are endless.

Look, I’m not a crazy person. I know that my foot book wasn’t a Duchamp or a Banksy. It wasn’t going to inaugurate some new era of art. Frankly, I’m not even sure I see myself as an artist. (I own a hostel and help run a marketing company.) But I’m also not sure that my book doesn’t deserve an audience, even if that audience is moved more by the irony of the situation than by the content of the book itself. I made something that grew from a professional and personal frustration with the state of the book industry. It resonated, and it had its place in the Amazon catalogue after they approved it, even if the point I was making left a little egg on Amazon’s face in the process.

This isn’t a point about what Amazon can do; it’s a point about what they should do. One of the stories of our time is how much control we cede to technology companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, and, yes, Amazon. We give them our clicks, our money, our attention, and, in some cases, our judgments, often without thinking about what we’re handing over. But it’s important to ask when lines are crossed, when we might have given away too much to these huge impersonalities. That might be when Apple can determine what to share with the FBI in a criminal investigation. It might be when Google can sell your web history to advertisers looking to hawk their wares. It might be when Facebook chooses what does and doesn’t get top billing in the newsfeed. And it might be when Amazon decides what does and does not constitute art. I don’t have absolute answers to these questions, but I think the questions are worthy ones to raise–and that they don’t get raised often enough.

* * *

Luckily, after failed attempts with Amazon, I was approached by a publishing company who wanted to help me: Thought Catalog. They’ve graciously agreed to re-issue “Putting My Foot Down.” I find it exhausting when someone spends too much time explaining their creations, so I won’t say much more other than to say that this is a revised and expanded edition. It captures the interaction between the art, the audience, and the artist.

So here we are, together “Putting My Foot Down” again. Enjoy. ![]()