What Your Accent Says About You

Perhaps accents are meant to reflect culture and background, and people feel duped when they are “acquired.” I find this a limited definition. Rather, accents are often coincidental.

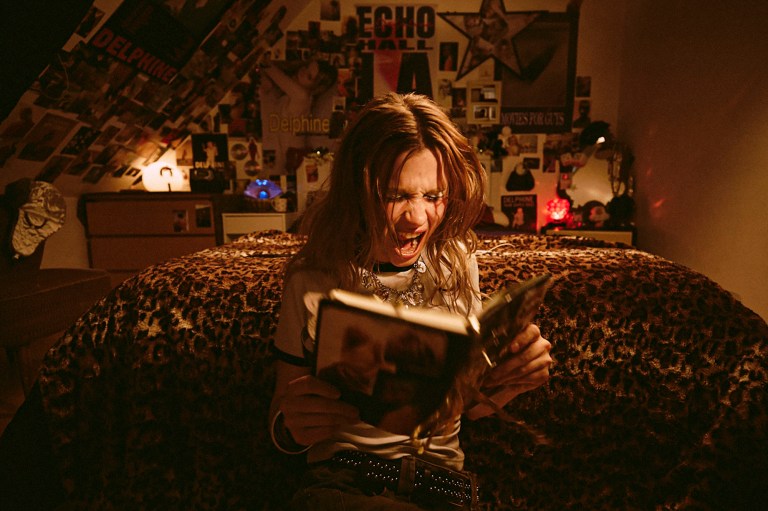

By ![]() Lin King

Lin King

“Maybe the girls there will find it cute that an American dude speaks their language with an accent,” a friend of mine mused before leaving for a language program in Asia.

“Is that a thing?” I asked.

“Well, you know how American girls find it cute when guys have an accent?”

“They do?”

“Yeah, like a French or Italian one or something.”

“Right, but not an Asian one.”

“Right.”

In 2012, CNN conducted a Facebook poll on “the world’s sexiest accent.” Though this is hardly scientific, the article citing the poll does have 20,066 likes, so I’ll just work under the premise that the Internet have certified it as fresh. Out of interest, the top five winners were Trinadidian, French, British Oxford, Spanish, and Italian. Keeping in mind that these are the preferences of a select group — CNN frequenters, online poll enthusiasts, etc. — it is undeniable that certain accents tend to be preferred over others.

I have not studied linguistics, nor the psychology involved, and I’m not trying to assume any authority. I have, however, been fascinated by the unequal treatment of accents for a long time.

Currently, at age 20, I am an English major at an American university. Through my speech, people have guessed that I’m from Jersey, or Illinois, or maybe California. At age 9, however, I was nagging at my dad to confirm that I could spell “people”, the most difficult English word I knew, in preparation for class at my Taiwanese public school. I said it more like “peepoh”.

Prior to this, my only contact with English had been through my Filipino nanny, Nelda. As an only child with working parents, I spent much of my time with her, and since she spoke an assortment of Filipino-accented English and piecemeal Mandarin Chinese, I, too, began tossing “becus” and “dees, dat” into the mix.

Nelda did not stay for long, but later my parents told me that when they overheard us talking, they would have expected to find a Filipino girl. My parents, who had each spent more than a decade in the US, both spoke English quite fluently. Though they intended for me to eventually attend an American college, they wanted my early education to build a strong base in Mandarin. Thus, before Nelda, my English was a blank slate, ready to follow whatever example it met.

With Nelda gone and my Taiwanese school commencing English lessons, I quickly adopted a crisper Taiwanese accent with flatter intonation. I did well on the quizzes, which involved memorizing basic vocabulary, and was confident in my skill. But one day, my friend who spent many summers in the US told me, “Your English doesn’t sound American.”

I was embarrassed. I did well in class, so why was my speech was less-than-perfect? When I brought this up to my mom, she explained that she and dad had accents too (this surprised me), that it was because they started learning English late, but that also didn’t mean their English was “bad.”

The year before I transferred to the Taipei American School at age 11, I resolved to practice English everyday by reading Harry Potter and watching the movies religiously. My accent quickly morphed to match the films’, not because of Anglophilia but because my life goal was (is) to be Emma Watson. That summer, when my dad took me to see Prisoner of Azkaban in theaters, the audio track malfunctioned and switched to the Mandarin dub. I clearly remember crying passionately: “They simply cahn’t do that!”

The British phase was short-lived. After transferring to the American School, I was placed in ESL and worked hard to get out. This meant studying, but also assimilating; soon I was saying “duh” and “whatever,” donning bracelets from Claire’s, and spelling aeroplane the “right” way. Eight years later, starting college in the States, nobody suspected me of being an international student. Some expressed disbelief. “But you don’t have an accent!” is the objection that I have learned to anticipate.

I sometimes wonder how my life would be different now if I had kept one of my former accents. How would my friends have perceived me if I had introduced myself with a Filipino or Taiwanese tongue? Would they have been as approachable, or would I have been dismissed as a “fob”? And what if I had kept a British flair? One of my best friends is an American who was raised in London, but never acquired an English accent. We sometimes joke that, should she have one, she would be in a very different social crowd — one that is, by high school terminology, “popular.”

Sometimes, I feel as though I’ve settled on the most boring option possible. Now, there is no way to change my decision without grouping myself with Jenna Maloney. Accent-shaming is a common phenomenon, whether it’s mocking of an original accent (think Bruno) or hating on a “fake” one (think Madonna). But why are people so adamant about a “real” accent?

Perhaps accents are meant to reflect culture and background, and people feel duped when they are “acquired.” I find this a limited definition. Rather, accents are often coincidental. Where you live, how your parents talk, where you went to school, what mass media you follow — there are countless influences that add up in undefined ratios. Whether we find an accent to be sophisticated or scathing is just as much an accumulation of personal experiences: I, for one, do not associate heavy Chinese accents with comedy, but real life.

Whatever accent you prefer, try asking people for the stories behind theirs — they may be more complex than you’d expect. ![]()