How I Became An Orgasm Donor

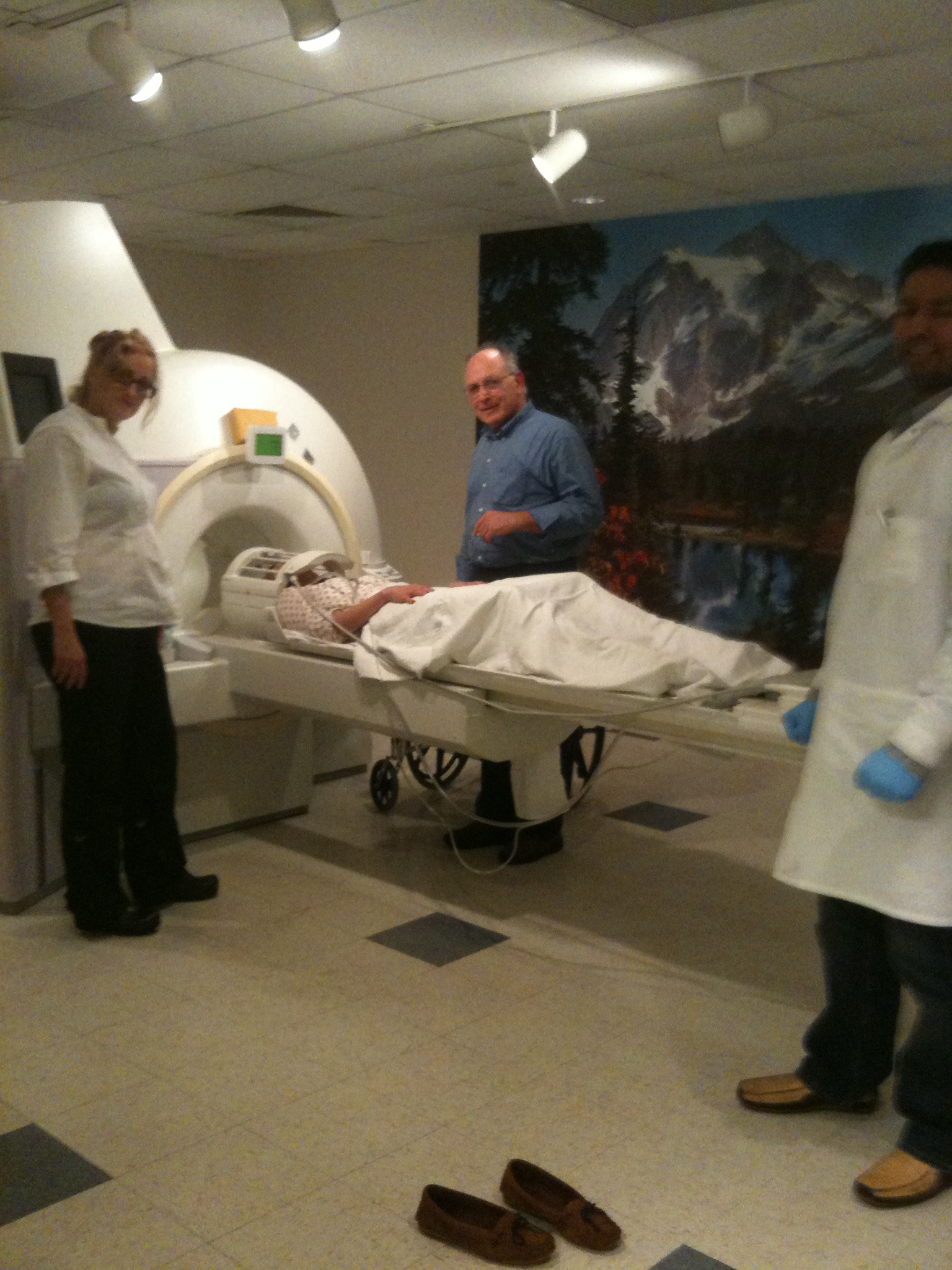

Perched atop an exam table at Rutgers’ Imaging Center, twitching bare feet, I glance from the standard medical gown keeping me cold to drab linoleum floor to unforgiving fluorescent ceiling lights. The back wall’s landscape mural fails to distract me from the elephant in the room: A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine with an offensively small cylindrical opening. I’ve volunteered to participate in a study that requires masturbating from within this behemoth while a team of scientists led by Barry Komisaruk, PhD, a Professor of Psychology and the author of several books on human sexuality, monitors my brain.

In spite of mounting anxiety, I allow Komisaruk and his colleague, Meryl Streep lookalike Nan Wise, LCSW, to enclose my upper body in a cage-like device. Within seconds, I can no longer budge my neck or head—at all. Thanks to large headphones connected to a microphone through which Komisaruk will eventually communicate with me, I am also deaf to my surroundings.

I remind myself that the aim of this experiment—to create a sensory homunculus (a map, essentially) of the female brain during climax, the male equivalent of which has long existed—is honorable and essential. But no matter how helpful my participation might be to the 24 to 37 percent of women who report trouble orgasming, the fact is that I am supremely uncomfortable, and I have never felt less sexy.

How the hell am I supposed to get myself off under these conditions?

As Komisaruk and Wise guide me into recline, each grasping one clammy hand, I try to drain my mouth of fast accumulating saliva. But the natural chin motion required to do so isn’t possible. Overwhelmed by this additional sacrifice in body functionality, I flail arms and kick up legs, a turtle on its back desperate to turn over.

“Deep breaths,” Komisaruk coaches while releasing me from headgear.

“I’m so sorry,” I clamor.

The truth is that we know embarrassingly little about female orgasm, a phenomenon that’s less easily measured than its more mechanical, splash-finale male counterpart. So when presented with the opportunity to help Dr. Komisaruk decode the female brain—and, however selfishly, to obtain some information on the inner workings of my personal sensual department—I couldn’t resist. Luckily, Komisaruk welcomes volunteers, most of whom find him by word of mouth, like I did.

A week before I trekked from New York City to Rutgers campus in Newark, New Jersey, Wise rang me to chat about my upcoming contribution to science. She explained that the data they planned to collect would be grouped with other participants’ to create a time course depiction of the areas activated at the start of stimulation, throughout build-up, and during orgasmic resolution.

“The more we know, the better equipped we’ll be to help the millions of women suffering from Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD),” she said. “There are even potential pain-blocking applications to understanding these neural pathways.”

Visual stimulus would not be provided during the experiment, Wise said, and while dildos were permitted, a clitoral climax was preferred for the sake of consistency (most participants before me had opted against a prop).

“One other thing I have to emphasize is that you can’t move anything other than your hand.”

“I can’t move my hips? At all?” I gasped, envisioning the pelvic thrusting upon which I rely heavily when touching myself down there.

“Our heads are vulnerable when any body part budges, and even a millimeter wriggle will compromise the data, Sweetie. It’s doable, though, I promise.”

Wise was right. I was not their first guinea pig, after all. Plus, there are people out there who report thinking themselves to climax.

“I can do it,” I declared. I would just have to practice.

Seven days later, I entered Rutger’s Psychology Department somewhat proficient at playing statue while masturbating.

Wise greeted me in an oversized white blouse, hair tousled, air calm. She introduced me to Dr. Komisaruk, who, in black slacks and a blue oxford, seemed refreshingly at ease as well.

“I realize we demand a lot from our subjects,” said Komisaruk while scuttling about to collect release forms and gather the tools to shape my mask.

As I lay atop a cushioned table, Komisaruk customized sheets of white mesh plastic to match the contours of my face and the back of my head after heating them in hot water. The finished product would make a solid Halloween costume, I joked.

By that point, any reservations I had about performing the most intimate of acts in front of people were sidelined by the kinship I felt with Komisaruk and Wise, who clearly cared deeply about their research. There would be four others I had not yet met watching me through an observation window while I went about my business, but I felt good about my role in the project and those guiding me through it.

If only I had been able to preserve this sense of well-being when transferred from office to hospital.

At the Imaging Center an hour later, robbed of too many faculties in an environment neither cozy nor sensual, I continue to panic.

Freed from restraints, I hunch over to heave in and out.

“This isn’t an abnormal reaction,” says Komisaruk.

“Drink some water,” advises Wise.

Eventually, I manage to sit upright, at which point I note four pairs of strange eyes peering back at me. Suddenly, it matters how these four lab coats might see me. My special rotating hand movement! My o-face! Shouldn’t we all at least have dinner first?

At Wise’s behest, I drag myself into the observation room to rest, where a young male technician and three female students greet me. Each congratulates me on my courage. One girl who holds a copy of “Do Gentleman Really Prefer Blondes?” kindly briefs me on some of the science behind sex, love, and attraction.

How can I disappoint such a warm group so dedicated to an important cause?

Half an hour and a few sips of water later, I collect my bearings.

Positioned inside the fMRI, I breeze through preliminary exercises. I complete five rounds of kegels in 30-second increments punctuated by 30-second rest periods. It’s easy to clench and release my vaginal muscles when instructed, but I have to work hard not to do so while at rest because I’m still thinking about the motion. To distract myself, I hum “Like A Virgin.” When Komisaruk asks me to “commence nipple tapping” (another warm up) in the husky voice of an older man, I manage not to crack up.

Finally, I am told to “begin clitoral self-stimulation.”

When a few of my go-to circular motions prove futile, I begin to perspire. Again, I am the young adult struggling to decipher her anatomy. I curse my body for producing moisture in my armpits rather than my private parts, but self-loathing only leads to more sweating.

This is when I realize that negativity and self-doubt are self-defeating. To orgasm, I have to feel good. I have to get in the right mindset in spite of my current confines.

To separate myself from my surroundings, my discomfort, and my audience, I imagine some of the best sex I’ve ever had. I relive the flirtation that stemmed from instant chemistry with my current boyfriend. I remember how we couldn’t resist ripping each other’s clothes off as soon as we were alone together. How I straddled him while he looked at me with those charmingly devilish eyes. I recall the extended seconds between the times at which the tip and shaft of his penis entered me for the first time. I become wet and aroused, as I was then.

At the onset of orgasm, I raise my left hand (the agreed upon signal). When the sensation passes, I lower it, smiling.

Afterward, Dr. Komisaruk and his team thank me profusely. Immersed in the after glow of fulfillment, I am happy to have helped, and happier yet to know that I’m capable of letting go in the least promising circumstances.

A few weeks later, I return to Rutgers to review the results with Dr. Komisaruk and Wise, who point out that my scans depict neurological activation in the expected regions. This is reassuring, but the green dots speckled across my brain’s pleasure centers seem like just that in the end. Of greater note is the news that I’m a “good candidate for multiple orgasms” since I climaxed within a relatively short amount of time (2 minutes and 6 seconds).

But the real takeaway is recalling my fMRI achievement—and what it means about the elasticity of our minds and bodies. The possibilities, it seems, are truly limitless. ![]()

Like this article? Check out the author’s book Surviving in Spirit via iBooks or Amazon.

A version of this story was originally published in the October 2011 issue of Cosmopolitan.