Guillermo Del Toro Says He’d ‘Rather Die’ Than Use AI – And That Defiant Stance Created The Most Beautifully Human ‘Frankenstein’ Ever Filmed

By Erin Whitten

Guillermo Del Toro has long been clear about his animosity toward generative AI. During a screening last month, he simply laid out the facts as he saw them… “Fuck AI”

At a more recent event, he said he would “rather die” than use it. To Del Toro, machine-made images are an empty artifice, a shortcut that deprives art of the work, the risk, the love, the struggle, the beauty that make it real. “Semi-compelling screensavers,” he has called AI’s output purposeless images with no intention, no labor, no pain, no human flaws and longings to push them into moving pictures. Del Toro’s rejection of AI isn’t just rhetoric and with Frankenstein? He has finally made the perfect expression of everything he knows real creation must be.

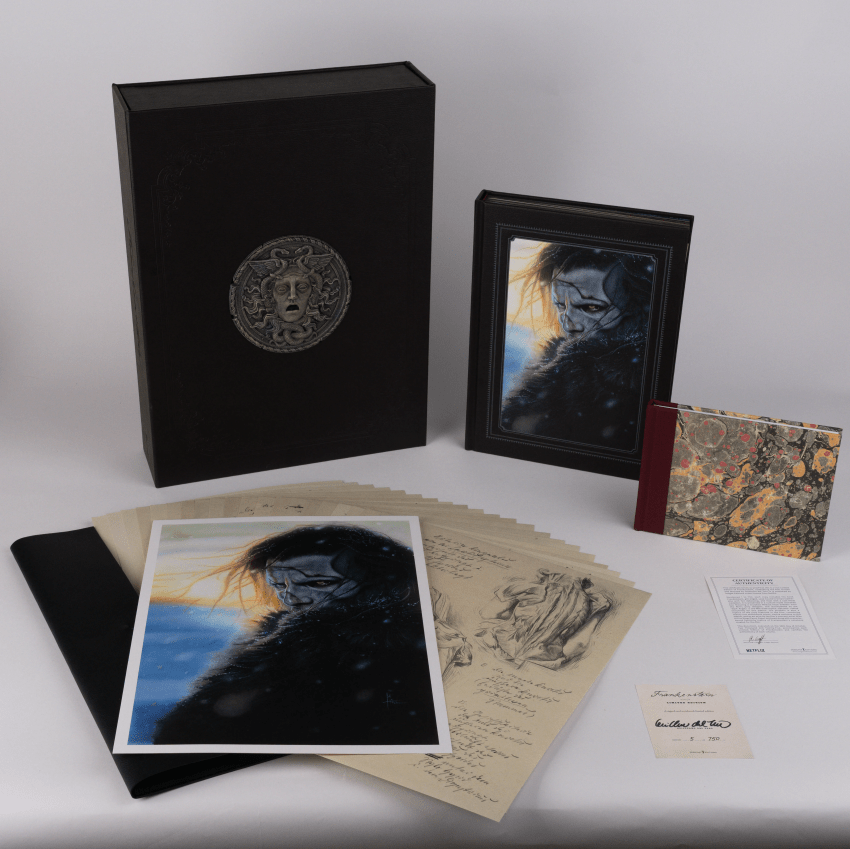

Del Toro has been building toward Frankenstein for most of his life. “All my life I’ve been aiming towards this movie, all 50 years of craft,” he said ahead of the film’s debut. Shelley’s novel has been part of his DNA for decades, from Cronos to Crimson Peak, every movie rehearsing some idea or some image he would deepen here. The notebooks, drawings, and journals that appear in The Art & Making of Frankenstein reveal a filmmaker who designs by hand, who thinks with pen and paper, who obsessively sketches and erases and sketches again until his instincts and his emotions connect. Oscar Isaac told the same story, sitting in Del Toro’s kitchen, eating Cuban food and talking about their fathers, the wounds they inherited from war. Conversation…not algorithms, not automated processes became the seed of Victor Frankenstein.

Del Toro’s handcrafted ethos flows through every department of the film. Production designer Tamara Deverell spent months building the immense laboratory inside an abandoned Scottish stone building, with its great circular window and rigorously weathered and aged equipment. When she first stepped inside the completed set, she couldn’t help but repeat the novel: “It’s alive!” She and Del Toro did not work through spreadsheets or procedurally generated graphics, instead, they shared visual references, visited old sewage plants and towers in Scotland, and constantly traded paintings and architectural details.

Creature designer Mike Hill designed Jacob Elordi’s Creature with the same attention to human detail. Del Toro did not want a mechanical monster stitched together he wanted a newborn, raw and vulnerable. Hill avoided any prosthetic that would distract from the eyes, the soul, because Del Toro was adamant the audience must feel for the Creature more than fear him. The team sculpted skin that looked like a “first draft” of life, something imperfect, fragile, and touchable. Every appliance was hand-built and then moved each day so Elordi’s performance could break through the prosthetics instead of being overwhelmed by them.

The work continued in the costumes, where Kate Hawley’s team spent months testing pigments and fabric until Mia Goth’s dresses glowed like living things in Dan Laustsen’s candle-lit cinematography. The color Claire wears, the film’s dominant color of blood, rage, and memory and Elizabeth’s malachite green required unending trial and error. Nothing about those colors was automated. They were discovered through test after test, failures, camera tests and recalibrations. Hawley even joked that the Creature’s wardrobe became “a huge monster” in its own right, trashed by snow and mud and wolves and explosions until it somehow held its character’s journey in its frayed seams.

Laustsen’s cinematography also repudiates the sanitized and the clinically perfect. He often lit with candles, pumped smoke into the vast gothic spaces, and relied heavily on deep shadows and single-source light. Del Toro and Laustsen regularly argued about the blocking of shots, from left to right or right to left, not for efficiency but for emotional impact. They debated how a camera should move not because there was a good way and a bad way but because they sought the weight of a shot.

Even the score embodies human vulnerability. Composer Alexandre Desplat viewed the music as a way to articulate the Creature’s feelings, the things he never says. He used a large orchestra but layered it with delicate violin lines that Desplat wrote specifically to express the character’s vulnerability. When scoring the sequence of Victor assembling the Creature, Desplat initially imagined something horrifying or chaotic until he and Del Toro realized it should instead be viewed through the artist’s eyes, a waltz of creation.

Del Toro’s resistance to generative AI rests on deeper principles beyond creative habits. It is the spine of Frankenstein. His film stands as a statement that real monsters, real heartbreak, and real wonder can only come from living labor. His lifelong dream project has finally proven his point: art is alive only when the hands that make it are.