This Grisly Documentary Series Shines Light On One Of The Most Gruesome True Crime Cases Of All Times

By Erin Whitten

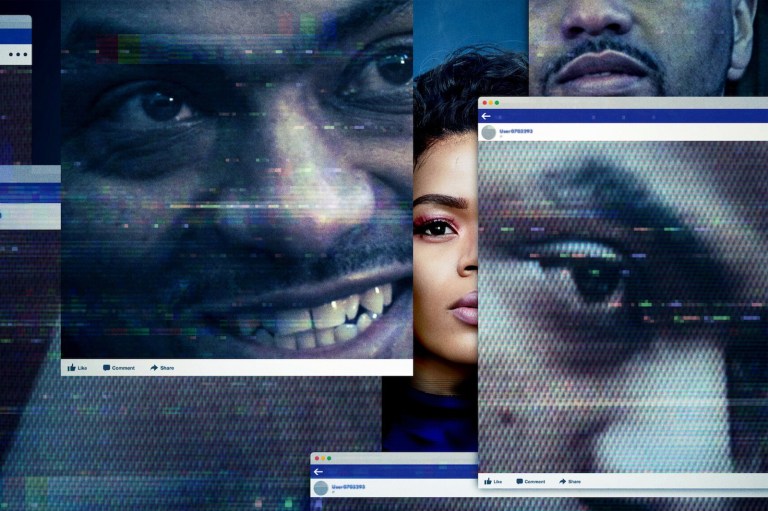

Netflix’s 2019 documentary series The Alcàsser Murders revisits one of the most horrific and inexplicable crimes of recent European history. The brutal murders of three Spanish girls shocked the nation in 1992 and even now, thirty years later, theories and debates over the case remain heated and inconclusive. The series, directed by Elías León Siminiani, digs deep into the evidence, the investigation, and the flaws of the original trial. As gripping as it is disturbing, the show paints a dark picture of what it’s like to live in an era when media and justice intersect in the public eye.

The night of November 13th, 1992, began like any other in the Valencian town of Alcàsser. Three teenage girls, Miriam García (14), Antonia “Toñi” Gómez (15), and Desirée Hernández (14) asked their parents to be allowed to go to a party that evening at the Coolor nightclub in a neighboring town, Picassent. Their parents agreed, not suspecting the dangers that awaited them on the road. In Spain, hitchhiking was not as dangerous as it is in the United States, and people were willing to pick up random hitchhikers even if they did not know their destination. After receiving permission from their parents to leave for the party, the three set out together to hitch a ride to the disco. Their parents would never see them alive again.

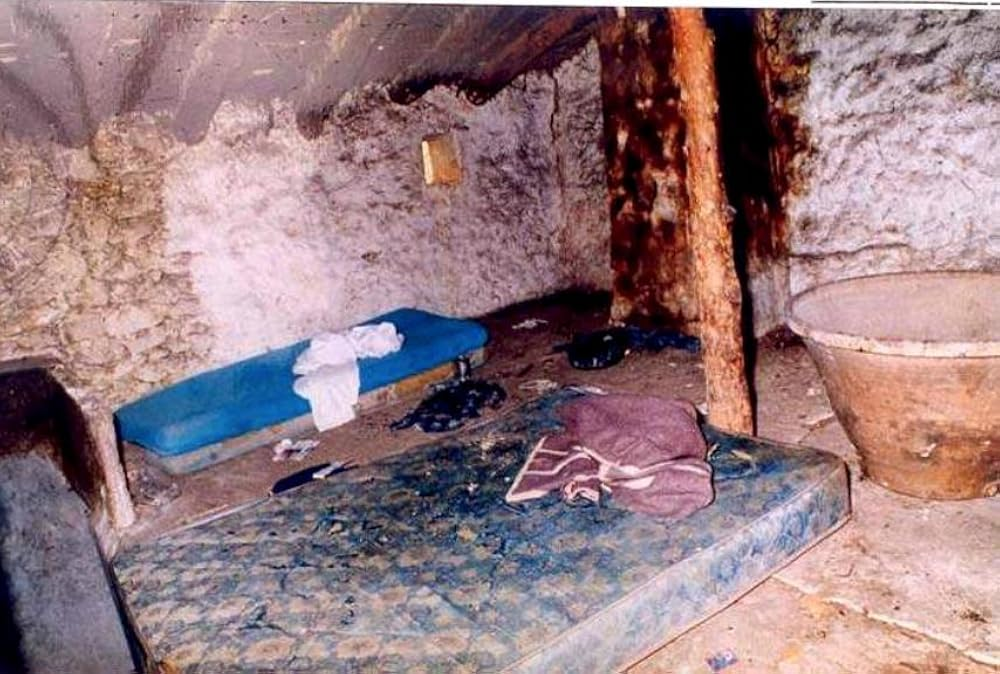

The disappearance of the girls set off Spain’s largest missing persons search to date. Newspaper, radio, and television were consumed by the case. Family members pleaded for information on live programs. Policemen combed the rural highways between Alcàsser and Picassent looking for clues. Search parties were organized and sponsored by community leaders and business groups. For three months, the whereabouts of the girls were unknown, until two beekeepers found the shallow graves of Miriam, Toñi, and Desirée on January 27th, 1993 in a wooded area known as La Romana near the Tous reservoir. The three girls’ bodies were found together in the single grave. The girls had been beaten, raped, and tortured before they were shot and buried. Autopsies later revealed that they had been gagged with their own clothing, blindfolded, beaten, bound, and sexually assaulted before being strangled, shot in the head, and buried. Injuries on their skulls and bones indicated both blunt force trauma and stab wounds.

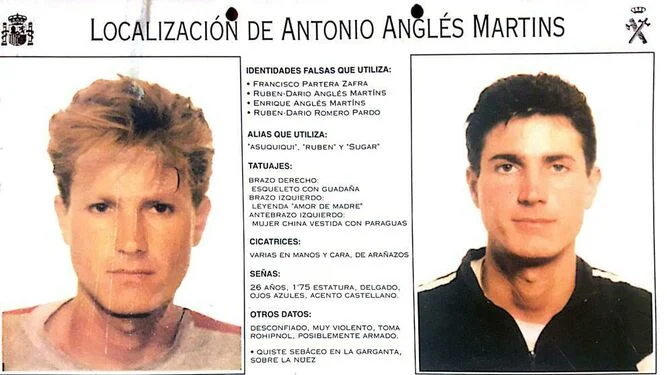

Two men were arrested on suspicion of the crime, Miguel Ricart and Antonio Anglés, both from the town of Catarroja. They were linked to the murder by eyewitness accounts and circumstantial evidence recovered near the gravesite. Ricart was apprehended on January 28th, 1993, but Anglés fled and a massive manhunt was put in place across Spain and internationally. According to police, Anglés had stolen multiple cars and police were alerted in various provinces after he eluded the law by changing his appearance and tactics. One of his last reported actions before he disappeared was boarding a British freighter called the City of Plymouth, which was bound for Dublin, Ireland. There are claims that he escaped before docking and jumped into the ocean. He has never been found since, despite regular sightings or leads in various countries. To this day, Anglés is Interpol’s most wanted fugitive.

Miguel Ricart’s case was sent to trial in 1997. The trial was one of the most highly publicized in Spain’s history. Ricart was found guilty of kidnapping, rape, and homicide, and sentenced to more than 170 years in prison. The prosecutors and judges believed that the crimes had been committed by a group of two individuals. They placed Anglés as the ringleader and Ricart as his underling or “street soldier.” Ricart, in his testimony, indicated that he felt that he had been forced to participate and that Anglés had either blackmailed him or directly threatened his family. The proceedings were at times gruesome, with photographs and graphic accounts of the crime dominating daily testimony.

The original autopsies had been lost or destroyed in subsequent handling. Photos of the girls’ corpses were leaked to tabloids; and multiple forensics and evidence protocols were either circumvented or ignored. The public and investigators alike became jaded and skeptical of the perpetrators, raising new questions as to whether powerful individuals or others may have been complicit in the acts or, more likely, in the potential coverup.

Autopsies on the three girls found seven different DNA samples from hairs not belonging to any of them, neither the victims nor the convicted perpetrators. There are concerns that other people had been present in the crime scene or that evidence had been mishandled or contaminated. This caused doubt on how the case was handled. Jewelry belonging to the victims was found at the scene and reported missing by the parents after the initial search, but then allegedly replaced during a subsequent search. After twenty-one years of Ricart’s sentence (Spanish law has a 30-year cap on maximum sentences, which has since been overturned), he was released from prison in 2013. He was greeted by a nation that had watched every development of the case for over two decades. Ricart’s release was met with hostility by the public, who largely believed him to be guilty. The disappearance and murder of the three Alcàsser girls remains one of the most notorious unsolved crimes in Spain and has been in regular rotation in the Spanish media. Fernando García, the father of Miriam García, became a media and political activist fighting for accountability in the justice system.

In the meantime, Antonio Anglés remains an enigma. He has reappeared in the news sporadically over the years. The skull of a man found on Lambay Island, Ireland, was investigated by Spanish police in 2021 as a possible lead but DNA confirmed it was not a match. He resurfaced in 2015 at the British pound-to-euro exchange rate when an Irish businessman was arrested by the Guardia Civil for swindling a London business of over £400,000, leading authorities to suggest that he was driving taxis in London. It is likely that Anglés is dead, possibly killed during the escape or shortly thereafter. The wounds and torture on the three victims have never been conclusively linked to the convicted perpetrators. The explanations, inactions, and acceptance of faulty or contaminated evidence have not satisfied the families or the public. Even now, experts question how forensic evidence was collected and not corroborated. The failure to account for every aspect of the physical evidence and the case itself means that new theories, angles, and cases continue to percolate, each offering a different revisionist take on one of Spain’s most violent criminal cases in recent history.

In many ways, The Alcàsser Murders documentary serves as a time capsule of the crime and the failed investigation that followed. It also underscores a profound loss of innocence for Spain and how it covered a crime of that nature in the early 1990s. The series reconstructs the investigative process and media coverage as if it were a contemporary coverage of its own. It is fascinating and chilling to watch the archival footage of the tragedy in real time, documenting not only the forensic bungling but also the media frenzy. Real talk show broadcasts are replayed in the documentary, showing live segments of the families asking for help as police searched the grounds. Tabloid coverage is shown with sensational headlines. Journalists speculate about everything from police incompetence to cover-ups. Autopsy photos were published in graphic detail. Tabloids interviewed convicted killers, untested psychics, and other random characters making up fanciful stories and wild conspiracy theories.

Director Elías León Siminiani’s approach is a deliberate effort to underscore both the crime and how the original investigation collapsed. The first few episodes move chronologically, covering the kidnapping, search, and eventual discovery. The second half of the series moves from the investigation and trial through the fallout and impact of the case. He approaches the entire subject as both a reconstruction and a social autopsy. He interviews journalists, lawyers, investigators, and family members about their individual impressions of the case and its handling, while providing stills, video, and transcripts from official proceedings. By putting together official testimony with personal impressions and recollections that conflict, the documentary provides a glimpse not only on what happened but what became of Spain after the crime.

There are consequences to the case even beyond the courtroom and TV screen. It has changed how Spanish authorities approach missing persons cases, created reform in police communication, and irrevocably altered the media landscape. It also created a generation that grew up conflating the news with entertainment, reducing the social impact of tragedy to “you had one job.” For the families, however, there is no end to the pain and suffering. The mothers of the victims, especially Fernando García (Miriam’s father), have been activists in the community and in politics, all while enduring their own public judgment.

The Alcàsser Murders forces folks to confront not only the heinousness of the crime but the addiction to the speculation and coverage of its own. It is sickening to watch but vital. It is a tragedy in so many ways, not just because of the crime itself but how and why it was allowed to be treated as entertainment. In the process, the truth itself becomes a casualty.