Hi, I’m Amy Glass. I wrote this article.

Do you think I’m really ignorant now? A monster?

The real story is that I used provocative language to start a conversation.

After I published my article, Thought Catalog published seven responses criticizing the article and Amy Glass. It also published two pro-Glass responses as well as one that largely reserved judgment, but presented good arguments for both sides of Glass-gate.

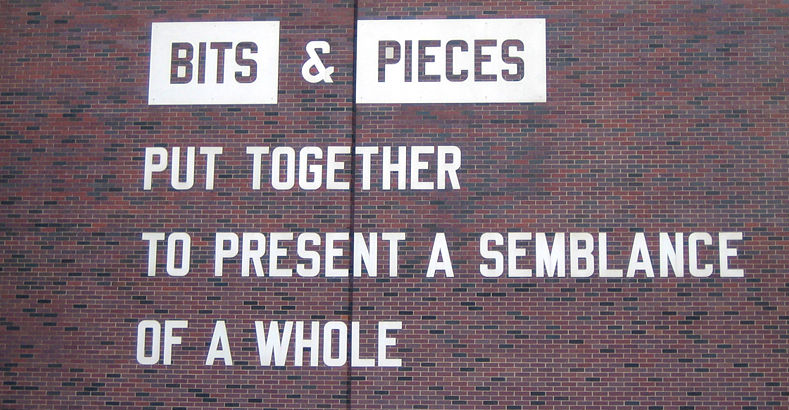

Do you know who solicited and formatted most of these articles? I did. They’re just as important as the original Glass article. Together, they create a conversation.

This isn’t backtracking. This is intellect. It’s the ability to explore ideas from multiple perspectives. It’s understanding and promoting the power of dialogue. It’s real. It serves the same function as fiction, whose authors create characters with different values, and as college professors, who educate their students about multiple sides of an argument.

I facilitated the resulting debate in a way that highlighted the diversity and complexity of realities that make up any singular idea.

Here are some of my favorite responses:

- An Open Letter To Moms by Rob Fee

- It’s About Time Amy Glass Talked About The Struggle Of Our “Role” As Women by Claire Goforth.

- Society Still Needs Family Woman by Ethan Sterling

- Judging Other People Does Not Make You Exceptional: An Open Letter To Amy Glass by Julie Horman

If you’re still here and want to know more, below is an FAQ.

Why use a pen name?

I created Amy Glass to write Successful Women Do Not Fall In Love. I didn’t want my friends and family to feel like I was subtweeting them—like I was telling them that none of their specific relationships inspire me. I love my friends and family and support them, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have a complex set of notions; it doesn’t mean I can’t struggle with what I believe, with what I judge as good or bad. I knew the opinion was controversial and warranted exploration and discussion, but wasn’t necessarily committed to it and didn’t want to alienate those close to me.

When the post generated so much heated interest, I saw how few women really talk about the realities of our place in the Western world. About how much easier men have it in the workplace because men don’t put in as much work at home. We’re stuck propagating this trope of “women can have it all” without realizing some of “it all” is shitty housework and less time to focus on ourselves. That’s a thought worthy of exploring.

On the internet—where there’s so much noise—I struck a chord with so many women. As Amy, I wanted to continue to speak to them via this vertical and explore what it was that was creating a spark.

What are you hiding?

Why is the author relevant? Amy Glass’ true identity has no relevance to the idea.

A pen name is a humble move. It says: I don’t know if I’m right, so I’m going play a part and explore the idea. I have the ability to write articles against stay-at-home moms and for stay-at-home moms.

The unimportant distraction is “Amy Glass.” Once people know who you are, they can discard the intellectual merits of your argument. Writing pseudonymously prevents the reader from redirecting attention to stuff that’s easier to process. It challenges them to focus on an intellectual task that requires more energy than making personal insults. By removing myself from the conversation, we can hone in on the issue.

Isn’t a pen name just a way to remove accountability?

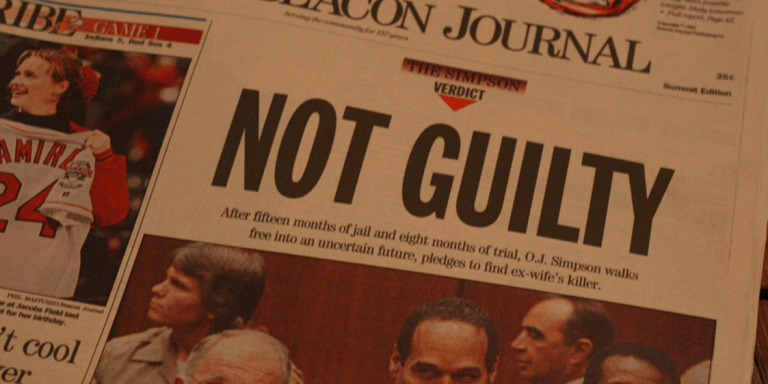

Yeah, sure. Using a pen name makes accountability more difficult. And this is a problem when people’s livelihoods are at stake—when, for example, you’re publishing unsubstantiated rumors that could destroy a person’s career, as in the case of Shirley Sherrod and Andrew Breitbart (Breitbart didn’t use a pen name, so we were able to hold him accountable). Accountability functions well in situations like these. The person who published these opinions can be disciplined and the publication is forced to reconsider their policy on pseudonymous publishing.

But in the case of Amy Glass, a pen name is justifiable. Amy Glass did not (and cannot) destroy anyone’s life by publishing “I Look Down On Young Women With Husbands And Kids And I’m Not Sorry.” It can make people feel bad, yes. It can make people rage, yes. But it can also lead to a massive, weeks-long discussion about the merits of the argument, rather than the merits of the person who published it. This distinction—exactly how the pen name is used—is crucial.

Do you really believe what you wrote?

I think of all my opinions as in transit. None of them are destinations: stagnant, immobile things that don’t change. I’m human—I have all sorts of ideas, and not all fall in line with one grand, value-consistent philosophy. Like Whitman, I am large, I contain multitudes.

You can read more about why I wrote “I Look Down On Young Women With Husbands And Kids And I’m Not Sorry” in this article.

Did you intend this to happen all along?

No, I didn’t intend to “reveal” myself as Amy—I wanted the focus to remain on the ideas.

Do you hate women/your mother?

My mom is a complete badass. When she was my age, she was flying around in helicopters saving people’s lives as an emergency nurse. She met my stepdad when they were both volunteer firefighters. She did a lot of things most women would never do alone, and I look up to her.

That said, most parents want more for their kids than what they had themselves. I think she went through so much effort to raise me so that I could try to be an even bigger badass than she was. That’s a value in our family: being a strong woman. Having ambition. Doing things that seem scary or outside of gender norms.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” I try hard to live up to this notion, rather than indulge in groupthink and lynching when an idea—independent of any one person or entity, but a momentary, sum product of a cultural system—disseminates through our environment.

For example: which question deserves more scrutiny and discussion—”Who is Edward Snowden?” or “What price are we willing to pay for national security?” Another: “Who are the police who brutalized Rodney King?” or “What systemic factors created the potential for a situation like this to happen, and why did the event catalyze the largest riots in the US since the 1960s?” One closer to home: “Who is Lena Dunham and what does her body look like?” or “Why does our culture fetishize rare female body types and recoil from average female body types?”

Right now, you have a choice that not many people on media-heavy diets get to actually consider: now that you know I’m Amy Glass, will you decide that I should be shamed for arguing a politically incorrect opinion?

Will you insist that reality is nuanced, or demand that it is black and white?

More importantly, you are in the position right now to consciously decide what’s more meaningful—discussing a controversial idea, or diverting discussion from that controversial idea to a discussion about the person who published it on the internet, as has been done so many times before.

Meritable discussion can be had about the unique characteristics that make up Edward Snowden, the Rodney King brutalizers, and Lena Dunham. But it’s probably clear which questions I think are more important.

If you’re still certain that I should be the focus of attention, rather than the discussion I’ve facilitated, you should buy my book and live tweet it to me @xsssy. And if you still sincerely hate me: I’m sorry. ![]()